From St. Louis to Boston, Scientists Grapple with Ethnoracial Divide in AD Biomarkers

Quick Links

Evidence suggests that ethnoracial groups in the U.S. have different rates of age-related dementias, with Hispanic/Latino and black or African American people generally being more affected and Asian-Americans being less affected than white people. Socioeconomic status also plays a role. It now appears that the predictive value of imaging and fluid biomarkers for AD can also vary by race or ethnicity. The advent of AD-targeted therapies underscores the importance of understanding these differences, but doing so is difficult so long as most participants in AD research and drug studies are white. At Enhancing Participation by Minoritized Groups in Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia Research, a conference held October 3 to 4 at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, stakeholders debated community-based recruitment strategies (see Part 1 of this series).

Three weeks later, at CTAD in Boston October 24 to 27, scientists showcased findings on ethnoracial differences from biomarker studies. Counterintuitively, perhaps, they reported lower rates of amyloid PET positivity among black and Hispanic relative to white participants. Overall, there was a push for more research on the underlying health and sociodemographic factors that underlie these differences.

Amyloid PET

In St. Louis, Consuelo Wilkins of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, had reported ethnoracial differences in amyloid PET positivity in the Imaging Dementia-Amyloid Scanning, aka IDEAS, study of some 20,000 Medicare recipients with MCI or dementia, 90 percent of whom were white (Wilkins et al., 2022; Rabinovici et al., 2019). In a secondary analysis, Wilkins and colleagues found that Asian, Hispanic, or black people were 53, 32, and 29 percent less likely to have a positive amyloid PET scan, respectively, than were white people.

New IDEAS attempts to understand these differences. It aims to enroll 7,000 people, including 4,000 who are black/African American or Hispanic/Latino, plus 3,000 people who can come from any ethnoracial group, including non-Hispanic whites. Wilkins heads recruitment strategies for the new study (link to Part 1). At CTAD, Charles Windon of the University of California, San Francisco, reported demographic details of the current enrollees. Twenty-two percent are black or African American, 19 Hispanic or Latino; 57 are neither.

Relative to the original, New IDEAS more than quadrupled the percentage of participants with few years of education. This varied substantially by ethnoracial background, with 36, 53, and 21 percent of black, Hispanic, and white participants reporting less than a high school degree, respectively. Importantly, a third of New IDEAS enrollees reported a household income of less than $75,000 per year, the current median in the U.S. This baseline characteristic differed by only 5 percent across ethnoracial groups. Finally, Hispanic or black participants were more cognitively impaired than their white counterparts.

Windon shared a glimpse of amyloid-PET results from the first 3,707 scans of New IDEAS. At 60 and 61 percent amyloid positivity, black and Hispanic people were slightly less likely to test positive for amyloid than non-black or Hispanic participants, of whom 68 percent did. Men and women were equally likely to have amyloid across ethnoracial groups. This differed from the original IDEAS study, in which women were more likely to be amyloid-positive, Windon reported. He has not yet stratified the PET data by other sociodemographic factors, cognitive status, or comorbidities.

At CTAD, Robin Wolz of Imperial College London presented amyloid-PET findings from Bio-HERMES. This biomarker study enrolled 956 participants with normal cognition, MCI, or mild dementia from 16 sites across the U.S. and Canada. White people comprised 76 percent of the cohort, while 10.7 percent were black or African American, and 11.4 percent Hispanic or Latino. Wolz reported that amyloid positivity on PET scans correlated with cognitive status across all ethnoracial groups. Among white people, 37 percent were amyloid-positive, compared to 26 percent of black/African Americans and 35 percent of Hispanic/Latino people. Interestingly, despite differences in amyloid positivity between blacks and whites as gauged by a central visual read, there were no differences in global cortical SUVRs across ethnoracial groups. To understand this discrepancy, Wolz suggested probing the relationship between regional SUVR and global amyloid positivity by race.

Amyloid-PET findings from the Health & Aging Brain Study-Health Disparities (HABS-HD) also revealed differences in amyloid positivity between groups. This biomarker study uses a community-based recruitment strategy to draw underrepresented groups, and has so far enrolled 1,600 Hispanic, 1,000 African American, and 1,300 white people (see Part 1). So far, 3,000 amyloid-PET and nearly 2,000 tau-PET scans are in the database, and in St. Louis, Sid O’Bryant of the University of North Texas in Fort Worth presented initial findings from the amyloid scans.

Jibing with other studies, O'Bryant saw that non-Hispanic whites were likelier to have positive amyloid scans than their African American or Hispanic counterparts. The difference was biggest among those with normal or mildly impaired cognition. For example, among those with MCI, 12 percent of African American and 10 percent of Hispanic people were amyloid-positive, compared to 33 percent of whites. Among those with dementia, only 43 percent of Hispanic or Latino people tested positive for amyloid, compared to 60 percent of African Americans and 63 percent of whites.

If It's Not Amyloid, Then What Is It?

O’Bryant also reported that MRI scans indicated a greater prevalence of neurodegeneration, starting at a younger age, in Hispanic/Latino than non-Hispanic white participants. He showed no tau-PET results but said that preliminary tau-PET findings point to Hispanic/Latino people being positive at younger ages than whites. O’Bryant suggested that the higher prevalence of neurodegeneration and tau pathology, despite lower prevalence of amyloid, among Hispanic or Latino people, may come down to co-morbidities. For example, preliminary findings from the HABS-HD study tied tau pathology to duration of diabetes. Hispanic/Latino people are likelier to develop diabetes than non-Hispanic whites, and do so about a decade earlier, O’Bryant said. He mentioned that this correlation between tau and diabetes duration was also seen in African Americans in this study.

At CTAD, Susan Landau of University of California, Berkeley, presented a variation on this theme. She compared the relationship between Aβ, tau, and cognition in two different cohort studies: ADNI, a clinic-based cohort that skews toward college-educated, wealthier, white participants, and U.S. POINTER, a community-based, more ethnoracially diverse cohort that preferentially recruits people with higher cardiovascular and other dementia risk factors.

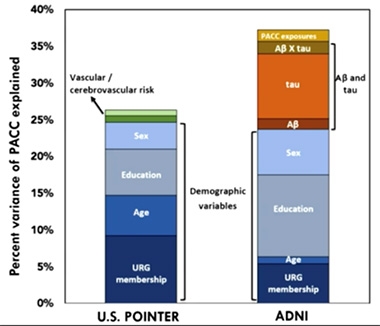

Strikingly, while a similar proportion of age, sex, and CDR-matched participants from these two cohorts tested positive for amyloid, Landau found that they differed markedly on amyloid’s relationship with tau and cognition. In ADNI, amyloid positivity explained twice as much of the variability in tau accumulation, as measured by tau-PET, as it did in POINTER. What’s more, a combination of amyloid and tau accumulation correlated strongly with flagging performance on the preclinical Alzheimer’s cognitive composite (PACC) in ADNI, but had no relationship with these test scores in POINTER. Yet, POINTER participants scored lower on the PACC than did ADNI volunteers.

ADNI versus POINTER. Aβ and tau together explained some cognitive variability in the ADNI cohort (right), but not in POINTER (left). Vascular problems explained a small proportion of cognitive variance in POINTER. [Courtesy of Susan Landau, UC Berkeley.]

If neither Aβ nor tau were to blame for memory problems in POINTER, what was? Landau reported that cardiovascular risk scores explained a smidgen of cognitive impairment in POINTER, but not in ADNI, though this effect disappeared when she adjusted for sex, education, and ethnoracial status. High blood pressure and white-matter hyperintensities—both indicators of vascular problems—accounted for a small amount of cognitive variance in POINTER, but not in ADNI. Being part of an underrepresented ethnoracial group (URG) influenced cognitive performance in both studies, but had more sway in POINTER.

This still left a lot to be explained. ADNI director Michael Weiner, University of California, San Francisco, pointed to a big difference between the cohorts: 45 percent of POINTER participants reported smoking at some point in their lives, versus 9 percent of ADNI participants. Besides smoking history, both studies have collected information on myriad additional health variables, such as diabetes, BMI, antihypertensive drugs, as well as social variables. Landau told Alzforum that so far, her analyses have ruled out smoking and diabetes as major contributors, but there are many more to examine.

Plasma Aβ42/40: The People’s Marker?

At CTAD, WashU scientists Suzanne Schindler and Chengjie Xiong each reported findings on a related issue: If amyloid PET generates different results across ethnoracial groups, how about plasma biomarkers? Schindler had previously reported that plasma phospho-tau markers appeared less predictive of brain amyloid positivity among African Americans than whites, though the current, intense search for canonical p-tau blood tests is changing the state of the field rapidly (Schindler et al., 2022). At CTAD, Schindler reported that among volunteers at WashU’s Knight ADRC, plasma Aβ42/40 ratio, as measured by C2N Diagnostic’s Precivity-AD test, picked out amyloid PET positivity equally well in both groups. Its predictive value held up regardless of age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, and BMI, Schindler reported.

For his part, Xiong compared plasma Aβ42/40 ratios between white and black people enrolled in SORTOUT-AB, a longitudinal study to evaluate potential racial differences in AD biomarkers in participants from the WashU, University of Pennsylvania, and University of Alabama ADRCs. He found that, on average, black people had a slightly lower ratio at baseline, which was driven by a higher average concentration of Aβ40. However, longitudinal change in the ratio was similar across racial groups. Importantly, plasma Aβ42/40 tracked similarly with other AD measures, including amyloid PET and cognition. In all, Xiong said, while black people may have a lower rate of amyloid positivity than whites, the plasma ratio of Aβ42/40 is equally predictive of amyloid in both (Xiong et al., 2022).

To Schindler's mind, the findings support the idea AD biomarkers can be found that work equally across ethnoracial groups. Even for those that don’t, Schindler urged the field to resist the temptation of using race-based biomarker cutoffs, for example by setting a lower threshold for biomarker abnormality to enroll minority groups into trials. This could select people who are less likely to respond to AD-specific treatments, Schindler noted. Rather, she called for a deeper understanding of the sociodemographic and health factors that underlie ethnoracial differences.

Overall, biomarker data available thus far point to the idea that people from underrepresented groups are less likely to have brain amyloid but more likely to be impaired. For some, this could mean that they have a non-AD dementia. For some, it could mean that they have less cognitive resilience, hence become symptomatic at a lower amount of amyloid pathology. These types of differences could arise from comorbidities, and/or from social determinants of health (SDOH).

At both the WashU conference and CTAD, scientists called for a greater understanding of SDOH, defined as the conditions in which people are born, grow, learn, work, live, and age. Some think SDOH may underlie differences in disease, biomarkers, and also in research participation, among people from different backgrounds.

SDOH are manifold and difficult to capture. Researchers are trying anyway. Megan Zuelsdorff, of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, co-chairs an NIA panel tasked with developing a way to measure these social determinants. In St. Louis, she described work toward a uniform scale. In its current iteration, the questionnaire is a 10-minute, self-administered test that takes stock of socioeconomic status, access to transportation, financial stress, healthcare experiences, discrimination, social connections, activities, and environment.

Others at the meeting presented pilot studies of SDOH batteries, including WashU’s Marissa Streitz and UPenn’s Shana Stites. Both teams had created their own SDOH batteries, then harmonized them to become the Social and Structural Determinants Influencing Aging and Dementia (SS-DIAD). By incorporating SDOH scales into their ADRC studies, researchers plan to investigate how these social factors relate to AD risk and pathogenesis, biomarkers, and research participation, and to what extent SDOH explain differences between groups.—Jessica Shugart

References

News Citations

Paper Citations

- Wilkins CH, Windon CC, Dilworth-Anderson P, Romanoff J, Gatsonis C, Hanna L, Apgar C, Gareen IF, Hill CV, Hillner BE, March A, Siegel BA, Whitmer RA, Carrillo MC, Rabinovici GD. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Amyloid PET Positivity in Individuals With Mild Cognitive Impairment or Dementia: A Secondary Analysis of the Imaging Dementia-Evidence for Amyloid Scanning (IDEAS) Cohort Study. JAMA Neurol. 2022 Oct 3;79(11):1139-47. PubMed.

- Rabinovici GD, Gatsonis C, Apgar C, Chaudhary K, Gareen I, Hanna L, Hendrix J, Hillner BE, Olson C, Lesman-Segev OH, Romanoff J, Siegel BA, Whitmer RA, Carrillo MC. Association of Amyloid Positron Emission Tomography With Subsequent Change in Clinical Management Among Medicare Beneficiaries With Mild Cognitive Impairment or Dementia. JAMA. 2019 Apr 2;321(13):1286-1294. PubMed.

- Schindler SE, Karikari TK, Ashton NJ, Henson RL, Yarasheski KE, West T, Meyer MR, Kirmess KM, Li Y, Saef B, Moulder KL, Bradford D, Fagan AM, Gordon BA, Benzinger TL, Balls-Berry J, Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Morris JC. Effect of Race on Prediction of Brain Amyloidosis by Plasma Aβ42/Aβ40, Phosphorylated Tau, and Neurofilament Light. Neurology. 2022 Jul 19;99(3):e245-e257. Epub 2022 Apr 21 PubMed.

- Xiong C, Wolk DA, Lah JJ, Gleason CE, Roberson ED, Benzinger TLS, Schindler SE, Fagan AM, Hassenstab JJ, Moulder KL, Balls-Berry JE, Sperling RA, Johnson KA, Levey AI, Johnson SC, Luo J, Gremminger E, Agboola F, Grant EA, Ances BM, Gordon BA, Hornbeck RC, Massoumzadeh P, Keefe SJ, Dierker D, Gray JD, Andrews J, Henson RL, Streitz M, Manzanares C, Qiu D, Mechanic-Hamilton D, Stites SD, Shaw LM, Midgett S, Morris JC. SORTOUT-AB: A Study of Race to Understand Alzheimer Biomarkers. Alzheimer's & Dementia, 07 December 2022

Further Reading

No Available Further Reading

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.