A Neurologist’s Devotion Puts Familial AD Research Onto New Plane

Quick Links

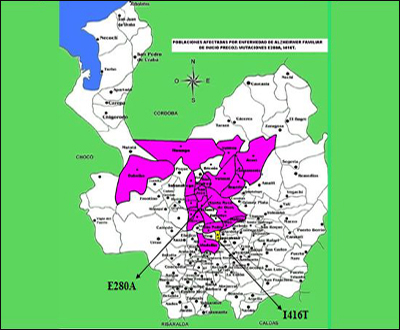

What has the Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative accomplished this past year? In February 2010, Eric Reiman and Pierre Tariot of the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute, Phoenix, Arizona, along with Kenneth Kosik of the University of California, Santa Barbara, traveled to Medellin, Colombia, to work onsite with Francisco Lopera at Universidad de Antioquia in Medellin. Lopera had begun working with families carrying the presenilin-1 Paisa mutation as early as 1980, first with a group in Belmira, and then spreading to include 25 extended families that encompass 5,000 members. The majority live in Medellin, Angostura, Yarumal, and Santa Rosa de Osos; others live in towns and villages in surrounding areas, including Belmira.

Francisco Lopera, above left, began working with this family in Belmira in 1980. Image credit: Francisco Lopera

Image credit: Francisco Lopera

During this visit, the API collaborators worked on setting up infrastructure for future trials and the accompanying biomarker research, as well as on procedures for screening and enrolling participants. They met families in different villages surrounding Medellin. “We consider the families partners in this. They moved us deeply. You cannot leave Colombia without being fully committed to their cause,” Reiman told the attendees of an API workshop held 7 January 2011 in Washington, D.C. Scientifically, researchers working with familial AD in API and in its sister initiative, the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Network (DIAN), argue that their work will generalize to the millions of people with sporadic late-onset AD. But what sets them apart most is that they confide being gripped on a deeper, personal level with a sense of obligation to relieve the families’ suffering. “Working with autosomal-dominant AD changes you as a person,” said Bill Klunk of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Klunk is part of the DIAN, and for many years has developed amyloid PET imaging in such families as a step toward preclinical drug trials in them and, eventually, in all AD.

Since last February, Lopera’s team at the University of Antioquia has screened around 800 family members for trial participation. The scientists enrolled them with neuropsychology tests, clinical exams, blood draws, as well as CSF sampling for fluid marker measurements and volumetric and functional MRI scans in a growing subset. The University of Antioquia has MR scanners; a cyclotron for amyloid imaging radioligand synthesis will be up and running soon, said Reiman. The goal is to screen another 750 relatives in 2011, aiming for 2,000 enrolled in total. About 660 of them are expected to carry the Paisa mutation.

These are huge numbers by the standards of autosomal-dominant AD research. Most prior published studies in families around the world had far fewer than 20 carriers. Even the DIAN, which to date has enrolled 150 participants to its ongoing observational studies and planned treatment trials in the U.S., Australia, and the U.K., is hard-pressed to match that number because most autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease (ADAD) families known to science are small and far flung.

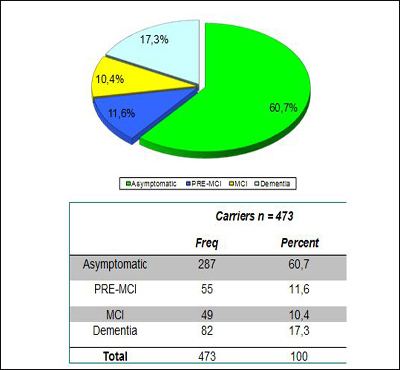

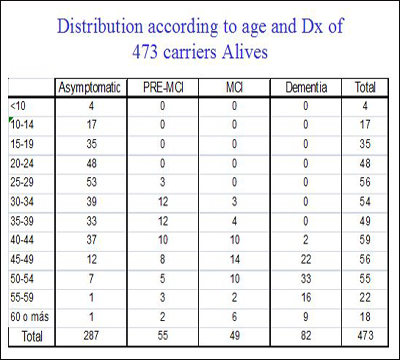

At the D.C. meeting, Lopera told the regulators, researchers, and funders that of the total Paisa lineage of 5,000, his team to date has studied 2,440 descendents. Of those, 1,107 escaped the mutation, 577 carry it, and 756 were not genotyped. Of the last, 506 are alive, as are 473 carriers and 1,096 non-carriers. For a precise breakdown of what stages of AD these carriers are in, and how old they are, Lopera generously made slides available for Alzforum readers. His data show that a small majority of the carriers enrolled so far are asymptomatic at present and are younger than 35. This is the age at which the researchers can now detect the very first signs of a subtle memory deficit (see Part 3 of this series). The cohort to date has about 100 carriers each in their twenties and thirties.

Image credit: Francisco Lopera

Image credit: Francisco Lopera

Lopera further said that of the 800 people screened so far, nine in 10 intend to participate in clinical trials. This is important, because in the U.S. and Europe, researchers historically have cited difficulties in finding willing trial participants among autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease (ADAD) families. This was true especially in the past, when coordinated efforts to approach trials in a partnership with families did not exist. DIAN is changing this reluctance in its participating countries, too. At the D.C. conference, DIAN investigators Nick Fox of University College, London, and Randy Bateman of Washington University, St. Louis, reinforced Lopera’s point, saying their study participants, too, want to enter treatment studies. Lopera emphasized that relatives say they want such trials even though they understand that the trial may come too late for themselves. Possibly helping their children is motivation enough for them (see also ARF related London story).

Pierre Tariot, Kenneth Kosik, F. Manes, and Francisco Lopera met with families in Angostura, Antioquia, in February 2010. Image credit: Francisco Lopera

Yakeel Quiroz is a graduate student at Boston University who did undergraduate work with Lopera. She still collaborates extensively with Lopera, and meets, comforts, and studies relatives of the Paisa mutation families. At the D.C. conference, Quiroz said, “When you work with these families, you see their emotional and financial burden. It is worse in familial than sporadic AD, because frequently more than one relative is sick at the same time. We see families that have three or four patients at different stages.” Indeed, a CNN documentary about these families showcased a woman, who is a nurse, and cares for a brother and a sister who are both mute, immobile, and require 24/7 care. The sister has been in this condition for nine years. Julie Noonan, an unaffected sibling of a U.S. family with FAD that was featured in the CNN documentary, also became a nurse after growing up with a mother who had succumbed similarly slowly to the disease. In the Colombian families, the disease starts in a person’s thirties, when people are providers to young children.

Edilma in Yarumal, Colombia. Image credit: Felipe Barral/CNN

Julie Noonan Lawson and Kate Preskenis. Image credit: Felipe Barral/CNN

What do the families want in return for the risk they take on with these trials? For one, they ask that the drugs have a reasonable safety record, Lopera said. This issue generated discussion at the D.C. conference, as API leaders asked regulators just how safe a drug must be for secondary prevention trials in FAD families. Generally, in the AD field, conversations about this topic are dominated by intense apprehension that an adverse drug effect in an outwardly still-healthy carrier could derail a company’s whole development program of a drug in question (see eFAD essays). That worry has held back such trials in the past.

To be mindful of both the families’ safety and skittish drug companies, the API leaders began their planning on the assumption that a drug for an FAD prevention trial would have to be chosen primarily on the basis of a strong safety record, even though in practice, that might come at the expense of the drug’s scientific rationale and mechanistic promise. Not necessary, the regulators from both the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency said. Russell Katz from the FDA called the concern being expressed about safety “somewhat overblown. The people in this PS1 population have a very bad disease. You need no more safety data than for any relatively large long-term study. Usually for that, you have early Phase 2-type data of some duration. That would be good enough even though these patients are apparently cognitively normal before they take the drug.” Cristina Sampaio of the EMA said, “I very much agree.” Usually in drug development, short-term safety tests in healthy volunteers precede longer trials in patients, but in this case it is logical to flip the order around such that short-term safety data gained in sporadic AD patients could precede longer-term trials in still-healthy mutation carriers. “This is a matter of common sense more than regulation,” Sampaio said, expressing confidence that a practical solution could be found. (For more of the regulators’ stance on preclinical AD trials, see Part 4 and Part 5.)

For another, the families asked that any successful drug be made available to their families after the trial ends. They also want researchers to offer a trial for their already symptomatic relatives, lest they be forgotten in the enthusiasm for preclinical trials. The families request information about the risk potential benefits, and mechanism of action of the candidate drugs. But by and large, they support the project enthusiastically. “The families are sick and tired of AD; they want to end it,” Quiroz said. They even express a sense of national pride that their country could contribute an important piece toward solving the world problem of AD.

While the families asked for nothing material, anyone working with them can plainly see that their needs are tremendous, said Tariot. They need adult diapers, walkers, anti-dementia medications, antidepressants, and antipsychotics, for example. Medical aids can relieve the patients’ symptoms and ease the daily work of caring for an incapacitated spouse or sibling year in and year out while the loved one’s middle-age heart remains strong. To help raise funds for caregiving supplies, Quiroz has set up a private foundation. Called the Forget Me Not Initiative, it offers ways of donating funds or connecting with Quiroz and colleagues to organize a fundraiser.

Incidentally, Quiroz pointed out, while the families are less educated and poorer than people in the U.S. or Europe, they are industrious and highly functional. They give devoted care to their relatives. Indeed, in their book The Alzheimer’s Solution, Prometheus Books, 2010, coauthors Kenneth Kosik and Ellen Clegg describe the quality of caregiving in this Colombian population as a starting point to argue for a more integrated approach to dementia care and prevention in the U.S. (see also ARF related CFIT story and Webinar). For the purposes of API, Quiroz said that the families are fully capable of complying with protocol requirements.

The API collaboration with the Banner Institute has given the families renewed hope, Lopera told ARF. Of the relatives who came to him for care and research decades ago, some had dropped out over the years because he could offer them no prospect of real change. But after the collaboration with the Banner Institute began last spring, word went around, and now old faces are returning and relatives and new families are coming forward. “Of the 800 people we screened last year, 450 are new,” Lopera told ARF.

This renewed engagement raises the stakes for everyone. Hopeful once again, the families are paying close attention to the project. “They now see they are not alone. They know there are many scientists in the world who are thinking of them,” Quiroz said. This makes getting started with therapeutic prevention trials a shared responsibility, the API researchers said. They called upon companies to participate not just by attending the API meetings, but also by making treatments available and collaborating actively. At the API meeting in Washington, Quiroz translated a message a patient in his early forties had given her. “I know for me it is too late, but please help my children.” This man is starting down the path of MCI, and he knows what will come for him, Quiroz said. (See Part 3 for new research data.)—Gabrielle Strobel.

This is Part 2 of a six-part series. See also Part 1, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6. View a PDF of the entire series.

References

News Citations

- Detecting Familial AD Ever Earlier: Subtle Memory Signs 15 Years Before

- London: Families Talk About Treatment Trials

- Scientists and Regulators Discuss Preclinical AD Trials

- Can Adaptive Trials Ride to the Rescue?

- Colombians Come to Fore in Alzheimer’s Research, Mass Media

- Time to Open the Kimono—Which Drugs in Preclinical Trials?

Webinar Citations

Other Citations

External Citations

Further Reading

No Available Further Reading

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.