Paris: Studies Strengthen Link Between Brain Injury and Dementia

Quick Links

July 18, 2011. Alzforum has covered the connection between traumatic brain injuries (TBI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in a recent series (see ARF related news story). Two presentations at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC, formerly ICAD) bolster that link. AAIC was held 16-21 July 2011 in Paris, France.

Severe brain injuries, such as traumatic brain injuries (TBI), have been shown to induce deposition of amyloid-β peptide and increase the risk of AD. How milder concussions, occurring repeatedly over time, might also lead to dementia is less clear. Some studies have shown that athletes who suffer repeated concussions develop a form of brain degeneration, different from AD, known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) (e.g., see ARF Live Discussion and ARF related news story). “Determining the prevalence of the two conditions and developing clinical and biomarkers for distinguishing the two are high priorities,” wrote Sam Gandy of the Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City in an e-mail to ARF.

But not everyone agrees that the two types of injuries lead to dementia via distinct mechanisms. “I don’t subscribe to the theory that repetitive head trauma results in some clinical entity that is completely different from Alzheimer’s disease,” said Christopher Randolph of Loyola University Medical Center in Chicago, Illinois. Instead, Randolph believes that repeated concussions from many years of playing contact sports may result in diminishing brain reserve—essentially making the brain less able to withstand damage as it accumulates throughout a person’s life. As a result, neurodegenerative diseases such as mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD occur at an earlier age than they normally would.

At AAIC, Randolph presented preliminary data to support his conclusion. In 2001, Randolph and colleagues had mailed a general health survey to more than 3,000 retired NFL players. All players over 50 who responded to that survey then received an additional survey in 2008. The second survey specifically focused on memory issues, including an Alzheimer’s screening questionnaire known as the AD8. The brainchild of James Galvin, now at New York University in New York City, the AD8 has been validated against the clinical dementia rating scale and against neuropsychological tests (see ARF Live Discussion).

In total, 513 people completed the follow-up surveys, including the AD8, which had to be taken by both the former player and his spouse. Just over 35 percent of respondents had an AD8 score of 2 or higher, which suggested possible dementia. “It is a remarkably high proportion of people with cognitive impairment,” said Randolph. “The average age of people who completed the surveys was 61, which is fairly young.”

Former players thought to have cognitive impairment were interviewed by telephone, and then 41 of them came in for neuropsychological testing. The tests included the Repeatable Battery for Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) and a short form of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-II. Their results were compared to those obtained by examining two groups of non-athletes: 41 demographically similar adults with no cognitive changes and a clinical sample of 81 people diagnosed with MCI.

These numbers are small. That said, the athletes showed definite signs of being impaired when compared to the demographically similar adults. In addition, their MCI was similar to that of other adults with MCI, except the athletes were slightly less impaired. “Our suspicion is that former athletes have higher rates of cognitive impairment than do non-athletes, and that their type of cognitive impairment looks very much like prodromal AD,” said Randolph. “However, we will need a larger prospective study to confirm this result.”

But not everyone is sold on the conclusion. “They propose that these former athletes have MCI, but our experience is that it is more likely to be CTE,” said Christopher Nowinski at the Boston University School of Medicine. “Right now, we don’t have any way to distinguish the two clinically.” Both AD and CTE can lead to dementia, but on pathological examination, AD brains show the presence of amyloid-β deposits, whereas CTE brains show more signs of tauopathy (see McKee et al., 2009).

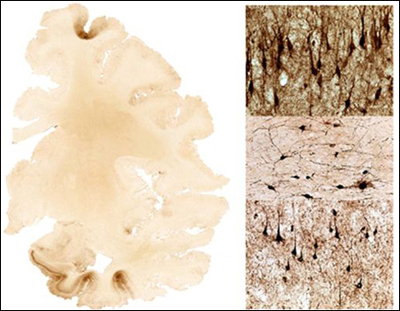

Brain section from a person with repeated traumatic brain injuries shows dense tau deposits in frontal cortex and medial temporal lobe (dark brown areas). The panels on the right show tau-positive neurofibrillary tangles and abnormal neurites. View larger image. Image credit: Ann McKee

The mechanistic link between TBI and AD is more established. However, it is not clear how prevalent TBI is, and to what degree it increases AD and dementia risk. “A particular challenge in determining the prevalence is the latency between injury and clinical manifestations,” said Gandy.

To help address such questions, Kristine Yaffe at the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues reviewed medical records of 281,540 U.S. veterans age 55 years and older who received care through the Veterans Health Administration. These people had had at least one inpatient or outpatient visit at some point in 1997-2000 (baseline period) and a follow-up visit in 2001–2007.

Yaffe and colleagues searched the database for people with a TBI diagnosis, including intracranial injury, concussion, skull fracture, and unspecified head injury. They then determined whether TBI of any type was associated with a greater risk of being diagnosed with dementia at the follow-up visit. The results, which were presented at AAIC, indicated that about 2 percent of older veterans had a TBI diagnosis during the baseline period. The risk of developing dementia was 15.3 percent for people with a TBI diagnosis compared with 6.8 for those without (p The results build on earlier findings from other groups (Plassman et al., 2000). What is new here is that “this is the largest study to date with almost 300,000 participants. We were able to look at mild TBI and subtypes of TBI, and the follow-up was seven years,” wrote Yaffe in an e-mail to ARF. “We also carefully adjusted for other variables, such as medical and psychiatric comorbidities.”

“The large sample size yielding very tight confidence intervals makes this an impressive effort,” wrote David Brody at Washington University in St. Louis in an e-mail to ARF. “Imaging and other biomarker-based assessments of an epidemiologically valid subset of the subjects would be a logical next step.”—Laura Bonetta.

References

News Citations

- Stress and Trauma: New Frontier Lures Alzheimer’s Researchers

- TDP-43 and Tau Entangle Athletes’ Nerves in Rare Motor Neuron Disease

Webinar Citations

- Sports Concussions, Dementia, and APOE Genotyping: What Can Scientists Tell the Public? What’s Up for Research?

- The AD8—Dementia Screen Ready for Prime Time?

Paper Citations

- McKee AC, Cantu RC, Nowinski CJ, Hedley-Whyte ET, Gavett BE, Budson AE, Santini VE, Lee HS, Kubilus CA, Stern RA. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009 Jul;68(7):709-35. PubMed.

- Plassman BL, Havlik RJ, Steffens DC, Helms MJ, Newman TN, Drosdick D, Phillips C, Gau BA, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Burke JR, Guralnik JM, Breitner JC. Documented head injury in early adulthood and risk of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. Neurology. 2000 Oct 24;55(8):1158-66. PubMed.

Other Citations

Further Reading

News

- TDP-43 and Tau Entangle Athletes’ Nerves in Rare Motor Neuron Disease

- Paris: Semagacestat Autopsy and Other News of Trial Tribulations

- Paris: More Trial News, Mixed at Best

- Paris: Beyond Genomics, French Science Draws on Populations, Patients

- Paris: Standardization a Hurdle for Spinal Fluid, Imaging Markers

- Stress and Trauma: New Frontier Lures Alzheimer’s Researchers

- Paris: Renamed ARIA, Vasogenic Edema Common to Anti-Amyloid Therapy

- Paris: President and All, French Science Takes the Stage

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.