A Country Doctor, But Oh So Much More: Francisco Lopera, 73

Quick Links

On Tuesday September 10, Francisco Lopera died of cancer at his home in Medellin, Colombia. He was 73, and only just beginning to see his life’s work come to fruition.

In fact, Lopera still had much to do. With his group, he was gearing up for a second Alzheimer’s disease prevention trial—chasing an antibody known to remove plaques with a small molecule intended to keep them from returning—in the people to whom he had devoted his life’s work.

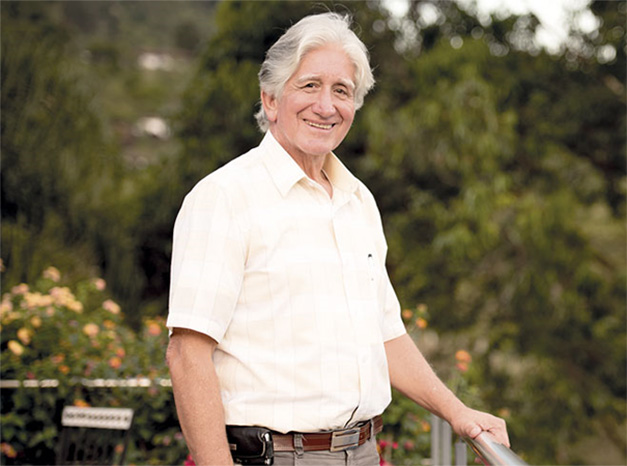

Francisco Lopera. [ Courtesy of the Consorcio de América Latina y el Caribe sobre la Demencia (LAC-CD).]

As a young country doctor in the early 1980s, Lopera realized that the villages in the mountainous Paisa region around Medellin where he had grown up were home to families beset with a heritable form of early onset dementia. Since then, Lopera focused his clinical work and his research on these families and their disease. The result? In large part, the Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative. The API, together with its cousin, the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Network (DIAN), has pioneered therapeutic intervention trials founded on large-scale human data gleaned from decades-long clinical and biomarker studies of deeply phenotyped cohorts.

This description hardly reflects the effort involved. Early on, Lopera and colleagues traced afflicted families and their genealogies, building pedigrees that pointed to a founder mutation in the 18th century. Lopera forged international collaborations with Ken Kosik, Alison Goate, and Cindy Lemere, and, in the 1990s, co-authored seminal papers on the presenilin 1 gene and the E280A mutation that caused autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease, named Paisa after its origin region (Alzheimer's Disease Collaborative Group et al., 1995; Lemere et al., 1996; Lendon et al., 1997; Lopera et al., 1997).

Grupo Neurociencias de Antioquia, aka GNA. [Courtesy of Group of Neuroscience.]

By and by, Lopera built the interdisciplinary Grupo Neurociencias de Antioquia at the University of Antioquia in Medellin. By the late 2000s, Lopera, with many colleagues, students and mentees, had collected information on, and built clinical care for and research relationships with, a thousand members of this kindred.

This was the largest Alzheimer’s kindred known at the time, but it was only a start. When in 2008 Lopera met Eric Reiman, Banner Alzheimer’s Institute in Phoenix, the two joined forces with Banner’s Pierre Tariot and Jessica Langbaum to make prevention trials a reality. For that, the Colombian API registry needed to grow, and now, in 2024, it contains 6,000 kindred members from age 7 to the late 70s, of whom 1,200 carry the mutation that leads to MCI at around age 44, and dementia by 49.

Lopera embraced Reiman’s idea of working to help his families in a way that would help AD patients across the world. When Reiman and U.S. colleagues visited Colombia in 2008, Lopera introduced them to a gathering of 700 family members and took them to visit affected families in their homes. “It was a life-changing experience,” Reiman recalled.

In 2009 and in 2010, the API scientists convened leading AD researchers, funders, FDA regulators, drug developers, and others to persuade them that the time had come, and the tools were in place, to start FDA license-enabling trials of the most promising investigational drugs in cognitively normal people whose genetics and biomarker profiles put them within five years or so of developing Alzheimer’s symptoms (Feb 2010 news series). Until then, leaders in the field had been paying lip service to this idea, calling it premature. At these gatherings, the pendulum swung toward action. “At the end, we went around the table, asking each participant for their concluding thoughts. Francisco was the last person to speak. When it was his turn, he simply said ‘My families are waiting,’ and everyone understood,” Reiman wrote in a 2023 letter recommending Lopera for the Potamkin Prize, which he won in 2024 (Mar 2010 conference news).

Francisco Lopera ringed by microphones and cameras at a GNA media event. Yakeel Quiroz, MGH, in red jacket on right. [Courtesy of Pierre Tariot.]

By 2011, API was in full gear, planning in detail for trials, bringing in more expertise. Media companies had caught on and were flocking to Medellin. In 2012, then-NIH director Francis Collins announced federal funding for API’s Colombia trial as part of the U.S. National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s (March 2011 news series; May 2012 news).

This trial evaluated Roche/Genentech’s antibody crenezumab. Together with DIAN’s trial of gantenerumab and solanezumab, these were the first prevention studies of disease-modifying drug candidates. Both missed their primary endpoint. In 2022, Lopera had to tell “his” families that there was still no drug that could forestall their family scourge (see Jennie Erin Smith’s profile in The New York Times).

Francisco Lopera was known for his love of dancing. [Courtesy of Pierre Tariot.]

That said, Lopera and many other scientists and drug developers considered the trial valuable preparation for the next one waiting in the wings. Much had been achieved. For this initial trial, the University of Antioquia’s first cyclotron, PET system with amyloid and tau ligands, and 3Tesla MRI were installed. For up to eight years, 254 middle-aged, working Colombians traveled sometimes significant distances for frequent assessments and dosing, including through COVID and occasional violence encountered en route. Despite it all, 94 percent completed the trial, a far higher rate than AD trials typically achieve elsewhere.

The trial validated innovative design features for future prevention studies. It included noncarriers for comparison and to obviate the need for genetic disclosure. It recorded the trajectory of blood-based and CSF biomarkers, and MRI and PET imaging, prior to the onset of a person’s symptoms. This information informs the next trial, which Lopera was hoping to announce this year. “His” families, after all, are still waiting.

As is the case for DIAN, ongoing biomarker research in the larger observational cohort has generated finding after finding. To cite but one, it found that the neurodegeneration marker neurofilament light starts changing in the blood of E280A carriers as early as 22 years prior to symptoms, in people’s 20s (Quiroz et al., 2020).

In the minds of his peers and the public, Lopera’s contribution to science is bound up in his work with the E280A kindred. Lesser known is that, in the course of attracting thousands of people in Colombia for dementia care over 40 years, the GNA has also identified and characterized members of genetic kindreds suffering from other forms of ADAD, as well as from frontotemporal dementia, and the vascular dementia called cerebral arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy, aka CADASIL.

Did you know Francisco Lopera? What did he mean to you? What did this obituary leave out? For the comfort of his family and friends in Colombia and elsewhere, and to teach the many young scientists joining the field these days, share a memory, a vignette, an image. Email gstrobel@alzforum.org or type into the comment field below.—Gabrielle Strobel

References

Mutations Citations

News Citations

- Phoenix: Vision of Shared Prevention Trials Lures Pharma to Table

- Phoenix: Trials in Colombia and the U.S. for Those at Highest Risk?

- Colombians Come to Fore in Alzheimer’s Research, Mass Media

- NIH Director Announces $100M Prevention Trial of Genentech Antibody

Therapeutics Citations

Paper Citations

- Alzheimer's Disease Collaborative Group. The structure of the presenilin 1 (S182) gene and identification of six novel mutations in early onset AD families. Nat Genet. 1995 Oct;11(2):219-22. PubMed.

- Lemere CA, Lopera F, Kosik KS, Lendon CL, Ossa J, Saido TC, Yamaguchi H, Ruiz A, Martinez A, Madrigal L, Hincapie L, Arango JC, Anthony DC, Koo EH, Goate AM, Selkoe DJ, Arango JC. The E280A presenilin 1 Alzheimer mutation produces increased A beta 42 deposition and severe cerebellar pathology. Nat Med. 1996 Oct;2(10):1146-50. PubMed.

- Lendon CL, Martinez A, Behrens IM, Kosik KS, Madrigal L, Norton J, Neuman R, Myers A, Busfield F, Wragg M, Arcos M, Arango Viana JC, Ossa J, Ruiz A, Goate AM, Lopera F. E280A PS-1 mutation causes Alzheimer's disease but age of onset is not modified by ApoE alleles. Hum Mutat. 1997;10(3):186-95. PubMed.

- Lopera F, Ardilla A, Martínez A, Madrigal L, Arango-Viana JC, Lemere CA, Arango-Lasprilla JC, Hincapíe L, Arcos-Burgos M, Ossa JE, Behrens IM, Norton J, Lendon C, Goate AM, Ruiz-Linares A, Rosselli M, Kosik KS. Clinical features of early-onset Alzheimer disease in a large kindred with an E280A presenilin-1 mutation. JAMA. 1997 Mar 12;277(10):793-9. PubMed.

- Quiroz YT, Zetterberg H, Reiman EM, Chen Y, Su Y, Fox-Fuller JT, Garcia G, Villegas A, Sepulveda-Falla D, Villada M, Arboleda-Velasquez JF, Guzmán-Vélez E, Vila-Castelar C, Gordon BA, Schultz SA, Protas HD, Ghisays V, Giraldo M, Tirado V, Baena A, Munoz C, Rios-Romenets S, Tariot PN, Blennow K, Lopera F. Plasma neurofilament light chain in the presenilin 1 E280A autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease kindred: a cross-sectional and longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2020 Jun;19(6):513-521. Epub 2020 May 26 PubMed.

External Citations

Further Reading

No Available Further Reading

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

Schepens Eye Research Institute and Harvard Medical School

I met Dr. Lopera while I was a medical student at the University of Antioquia in Medellín, Colombia. At the time, I was at a crossroads, uncertain about continuing a career in medicine. Through my interactions with Dr. Lopera, I found my path as a physician-scientist, which ultimately led me to join the laboratory of Kenneth Kosik at Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School. With Dr. Lopera's unwavering support, I was later accepted into a Ph.D. program at Harvard Medical School. Without his guidance, I likely would have left medicine. And without his support, how could a young man from Comuna 13 in Medellín have the chance to study at Harvard? Dr. Lopera helped many others, like myself, find their way in neuroscience, training scores of researchers, many of whom are now faculty at leading institutions around the world or part of his beloved Grupo de Neurociencias de Antioquia. He was the best mentor anyone could ask for. Everyone he trained felt special and unique—a gift that fostered deep connections that transcended time and space.

His remarkable work with the Colombian families affected by PSEN1 E280A laid the foundation for identifying APOE3 Christchurch and Reelin-COLBOS as candidate protective genes against Alzheimer’s disease. His research with APOE3 Christchurch showed the world that it is possible to delay Alzheimer’s for decades and, in my view, spearheaded a paradigm shift in Alzheimer’s research, encouraging a focus on protective factors. These protective genes are now paving the way for a new generation of therapies—ones that are inspired by protected cases and are likely to be safer and more effective than what we currently have.

Dr. Lopera deeply cared for his patients and was a pioneer in recognizing the social responsibility of those involved in clinical research. He believed it was essential to provide direct assistance to the patients and families devastated by familial Alzheimer’s disease. He would see patients in the morning and then spend the rest of the day ensuring that families in need had access to food, diapers, medications, beds, wheelchairs, and accommodations.

I am also pleased that his obituary highlighted Dr. Lopera's outstanding work with families suffering from other neurological conditions, such as CADASIL. Though less publicized, his work with CADASIL families was equally groundbreaking. In Colombia, he described the world’s largest CADASIL families, identified the causative mutations in NOTCH3, defined clear genotype-phenotype correlations, and contributed to the understanding of the role of Notch signaling in CADASIL pathophysiology.

References:

Arboleda-Velasquez JF, Lopera F, O'Hare M, Delgado-Tirado S, Marino C, Chmielewska N, Saez-Torres KL, Amarnani D, Schultz AP, Sperling RA, Leyton-Cifuentes D, Chen K, Baena A, Aguillon D, Rios-Romenets S, Giraldo M, Guzmán-Vélez E, Norton DJ, Pardilla-Delgado E, Artola A, Sanchez JS, Acosta-Uribe J, Lalli M, Kosik KS, Huentelman MJ, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Reiman RA, Luo J, Chen Y, Thiyyagura P, Su Y, Jun GR, Naymik M, Gai X, Bootwalla M, Ji J, Shen L, Miller JB, Kim LA, Tariot PN, Johnson KA, Reiman EM, Quiroz YT. Resistance to autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease in an APOE3 Christchurch homozygote: a case report. Nat Med. 2019 Nov;25(11):1680-1683. Epub 2019 Nov 4 PubMed.

Lopera F, Marino C, Chandrahas AS, O'Hare M, Villalba-Moreno ND, Aguillon D, Baena A, Sanchez JS, Vila-Castelar C, Ramirez Gomez L, Chmielewska N, Oliveira GM, Littau JL, Hartmann K, Park K, Krasemann S, Glatzel M, Schoemaker D, Gonzalez-Buendia L, Delgado-Tirado S, Arevalo-Alquichire S, Saez-Torres KL, Amarnani D, Kim LA, Mazzarino RC, Gordon H, Bocanegra Y, Villegas A, Gai X, Bootwalla M, Ji J, Shen L, Kosik KS, Su Y, Chen Y, Schultz A, Sperling RA, Johnson K, Reiman EM, Sepulveda-Falla D, Arboleda-Velasquez JF, Quiroz YT. Resilience to autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease in a Reelin-COLBOS heterozygous man. Nat Med. 2023 May;29(5):1243-1252. Epub 2023 May 15 PubMed.

Quiroz YT, Aguillon D, Aguirre-Acevedo DC, Vasquez D, Zuluaga Y, Baena AY, Madrigal L, Hincapié L, Sanchez JS, Langella S, Posada-Duque R, Littau JL, Villalba-Moreno ND, Vila-Castelar C, Ramirez Gomez L, Garcia G, Kaplan E, Rassi Vargas S, Ossa JA, Valderrama-Carmona P, Perez-Corredor P, Krasemann S, Glatzel M, Kosik KS, Johnson K, Sperling RA, Reiman EM, Sepulveda-Falla D, Lopera F, Arboleda-Velasquez JF. APOE3 Christchurch Heterozygosity and Autosomal Dominant Alzheimer's Disease. N Engl J Med. 2024 Jun 20;390(23):2156-2164. PubMed.

University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf

I have always been amazed by the impact of chance on our lives. Several coincidental events and unusual circumstances led me to meet Francisco Lopera at a crucial time in my life, when I was a pre-graduate medical student. He identified in me a deep yearning for knowledge and scientific research and welcomed me into his group at the University of Antioquia in Medellin at the beginning of my career. This fortuitous meeting led to a 25-year relationship that evolved from mentorship to friendship, shaping a troubled medical student in Colombia into a researcher with his own lab in Germany. My initial interest in Alzheimer’s disease and the needs of his group led me from working as a brain donation assistant to my current work in molecular neuropathology of this disorder. His guidance and wisdom supported me throughout.

I don’t think it makes sense to go into the details, here, of his more than 200 peer-reviewed publications, and numerous prizes, awards, and recognitions, or to specify his eclectic contributions to science and academia, which span over five decades and range from psychoanalysis to neurodegenerative diseases, and from clinical reports to basic sciences. It is enough to say that he enriched every endeavor or collaboration he was part of, often with keen observations or the most challenging question, regardless of his depth of knowledge on the subject.

His impact in the Alzheimer's field is immense, though it is more widely known in the Spanish-speaking world. I believe that his cumulative work and the ongoing research by his mentees will become increasingly relevant for future advances in the field.

Over the past 25 years, through travel and collaboration with numerous people, I have met many brilliant researchers, several unerring clinicians, a few wise teachers, way less humble and caring individuals, and very few truly great souls. Francisco Lopera was all of these things. I feel fortunate and privileged for having had him as my mentor and friend during that time. Wherever our current research will lead us, it will be thanks to his example and support. I hope it will honor his legacy.

University of California, Santa Barbara

Francisco Lopera: A Memory and a Tribute

Autumn already!–But why regret an eternal sun if we are embarked on the discovery of divine light–far from all those who fret over seasons.—Arthur Rimbaud

Farewell, Pacho. How grateful I am to have had a moment of farewell, to say goodbye when still the sparkle in your eyes remained.

Three and half decades ago, in 1989, Francisco Lopera told me about a very large family who suffered from dementia with onset in their late 40s. That moment began a collaboration rare among scientists for its uninterrupted duration. He and Lucia Madrigal had pieced together on tattered scraps of paper a family tree that, when pasted together and unfurled across a table, revealed hundreds of individuals, a number that later grew to thousands. Among the intertwining connections of marriages, of sons and daughters, of aunts and uncles, numerous cousins, and remote ancestors, what was apparent as Francisco listened to their stories was the fearsome presence of a disease that haunted them all. Thirty-five years ago, we did not know what that disease was until the first affected individual donated her brain and Juan Carlos Arrango flew with the brain to my house, in Boston at the time. It was 11 p.m. when he knocked on my door with a bucket and a brain in formalin. The next morning, we cut and stained the brain and confirmed the clinical suspicion of Alzheimer’s disease with all the diagnostic hallmarks of plaques and tangles. Today, the brain bank in Colombia known as NeuroBanco contains about 500 brains and has been an invaluable source of tissue for research.

A few years after proving the Alzheimer diagnosis, in collaboration with Alison Goate, the responsible mutation was identified in presenilin 1 as a substitution of a glutamic acid for an alanine at position 280. Blood samples for this analysis had been collected over the previous years and stored in refrigerators that lost power numerous times during those tumultuous years, often leaving dried blood along the walls of the tube. Once found, the mutation became known as the paisa mutation in recognition of the people in Antioquia and a few surrounding states called paisas. One stereotype of the paisas is that they are a proud people. On one occasion when I gave a talk in Cali there was a chuckle in the audience when I mentioned the paisa mutation. I asked what was funny. After all, the mutation causes a devasting disease. They said yes, of course, but the paisa are so proud, they are even proud of their mutation. The meaning of pride has changed since it made the list as one of the seven deadly sins to become a virtue regarding a sense of belonging to a group, and so was it with Francisco, a man deeply attached to his identity as a paisa. Despite offers from institutions all over the world he remained in Colombia, dedicated and at home.

Over the following years we traveled to the pueblitos of Antioquia through mountainous passes along winding roads, often stuck behind an exhaust-spewing overloaded truck struggling up the steep grade. These five- or six-hour trips began early in the morning, and after about two hours we always stopped for fresh pan de yuca and café con leche. Francisco pointed out a bend in the road on the way to San Raphael that was famous for kidnappings. Along with us, sometimes in a van, sometimes in an SUV, were Lucia and members of the Grupo Neurociencias team from the university. Conversation was boisterous and animated on the way out and sleepy on the return. Francisco, who was rousing, even a bit verbose when he delivered remarks to the family, listened quietly to the running chatter of the team.

With some advance planning at our destinations, the extended family gathered to receive us with big welcoming greetings and hugs. We walked into a modest home with 20 or 30 people already there and more coming and going as the day wore on. We brought snacks and juice boxes and sometimes the family prepared dinner for us. Most were family, a few were onlookers, as very little is private in the small towns and neighborhoods. The team wasted no time, first explaining our mission, to describe the disease which they knew all too well, the flip-of-a-coin inheritance pattern of an autosomal-dominant disease, the data collection process, and the acquisition of blood samples after carefully explaining informed consent to each subject.

The most animated moments were drawing the family trees. Family members huddled around Francisco as he asked about the parents and grandparents, the siblings and children, those affected and those who were healthy. Sometimes a key informant was missing, but a call to a neighbor reached a cousin who might open another branch of the family. Glances and half smiles across the room suggested more than was being said about paternity. In every family, there was at least one young man whose death was called an accident, but usually meant a murder. In this painstaking way, the family tree grew to thousands and new founder mutations surfaced. This was medical practice in reverse—not, they come to us, but rather, we go to them.

Colombia is a country of many wonders. It is a place of dreams and nightmares, of outlandish notions and mystical beliefs. It is not surprising that such a country has produced such a remarkable person as Francisco, as it has others whose global impact extends far beyond the small size of the country. In 2018, I flew with Francisco, his wife, Claramonika, and his daughter Karina to Acandí and from there we took a speed boat called a chalupa to Sapzurro near the Panamanian border. Like everything in Colombia—food, accents, slang—boats, too, are highly regionalized. We took a planchon to travel down the Sinú River to an indigenous village outside Monteria, a Johnson river boat to cross the Magdalena in the town of Suán. Sapzurro is the tiny town where Francisco did his “rural,” Colombia’s obligatory year of service after medical school. His medical school colleague Rafa joined us and they devoured chicharrones. An older woman there remembered him as the doctor who delivered her baby. She was effusive to see him.

For many years Francisco did this work in obscurity, with little money and zero recognition. I faced criticism from colleagues for what they saw as a human-interest story devoid of science. That began to change in 2004, when I brought Eric Reiman to Colombia and introduced him to Francisco. At last, the dream of offering hope in the form of a clinical trial could be realized. This hope had been part of every family visit, and soon, with the extraordinary efforts of Carole Ho, a clinical trial was on the drawing board. From the barrios of Medellin to the remote countryside, where healing was often in the hands of the bruja, or witch doctor, people endorsed a scientific trial that could benefit Alzheimer patients worldwide. I recall the first chapter of One Hundred Years of Solitude, in which the village people of Macondo lose their memories until one day a gypsy arrives and brings una sustancia de color apacible, a substance of a gentle color, and restores their memory. We sought the substance.

We now know the clinical trial did not show a therapeutic effect of treatment. But this trial was conducted like no other trial ever, thanks to the massive amount of groundwork laid down by Francisco as well as others including Lucia Madrigal, Silvia Rios, and David Aguillón, and most importantly, the trust the families placed in Francisco. This was a trial on a single family who all shared the same point mutation and shared a mostly similar socio-economic status. That platform to which numerous subjects donated their time and their bodies remains, and the population continues to collaborate with new trials that will be one of the many legacies left by Francisco.

More science came in 2019 when the APOE3 Christchurch variant was suggested by Yakeel Quiroz and Joseph Arboleda as the basis for delaying the onset of familial Alzheimer’s disease caused by the presenilin mutation. The discovery of this variant has spurred international research efforts to understand the mechanism of this protective effect.

Family trees conceal untold stories of love and romance, of death and despair. We all experience tragedy and joy but in Colombia the mix differs. Somehow both happen simultaneously. Like when I saw Francisco in his last days—unable to talk or move—and showed him some slides of our memories. One of them was me falling off a hammock at the finca, and from some unsuspected reserve, he laughed.

When Great Trees Fall

Maya Angelou

When great trees fall,

rocks on distant hills shudder,

lions hunker down

in tall grasses,

and even elephants

lumber after safety.

When great trees fall

in forests,

small things recoil into silence,

their senses

eroded beyond fear.

When great souls die,

the air around us becomes

light, rare, sterile.

We breathe, briefly.

Our eyes, briefly,

see with

a hurtful clarity.

Our memory, suddenly sharpened,

examines,

gnaws on kind words

unsaid,

promised walks

never taken.

Great souls die and

our reality, bound to

them, takes leave of us.

Our souls,

dependent upon their

nurture,

now shrink, wizened.

Our minds, formed

and informed by their

radiance, fall away.

We are not so much maddened

as reduced to the unutterable ignorance of

dark, cold

caves.

And when great souls die,

after a period peace blooms,

slowly and always

irregularly. Spaces fill

with a kind of

soothing electric vibration.

Our senses, restored, never

to be the same, whisper to us.

They existed. They existed.

We can be. Be and be better. For they existed.

Banner Alzheimer's Institute

Our relationship began in 2008, after Ken Kosik connected us to consider whether it was possible to conceive, fund and implement a prevention trial in ADAD. Alzforum captured several of the subsequent brainstorming meetings that we convened over the next few years, which Francisco attended as well. One particularly illuminating anecdote, mentioned in the obituary, still gives me gooseflesh. At the end of the first of these meetings, in late 2009 in Phoenix, we had received mixed opinions from our expert colleagues about whether AD prevention trials could be mounted. We asked each person to make a summary statement and Francisco had the last word. He paused, the room was silent, then he said quietly and slowly, “Our families ... are waiting ... for you.”

We came to Colombia many times and got to know him, his team, and the families very well. Like most great men, Francisco was complex. His many sides included loyalty, fierceness, anger, stubbornness, sometimes ruthless honesty, sometimes deft subtlety, humor, and a boisterous, captivating laugh. I recall one of our trips into the mountain jungle, heading to Angostura. It was not long after the FARC had stolen one of the group’s official GNA vans from a locked parking lot in Medellin. After being on a winding road with meandering cattle and dairy farmers for three hours, we saw roughly 200 young people walking single-file in a stream nearby. They carried weapons and wore camouflage, but I didn’t notice any insignia. I asked Francisco if this was the military. He reflected for a moment, and said, “If you think so.” No expression.

A couple of years ago, we had a long conversation about his work, and ours, and our lives. We talked about how long we could keep it up. He paused, and said, “I need to live a very long time so we can make the cure!” Then he roared with laughter. I did, too. Little did we know.

I called him our Lion, which he liked. We will all miss him terribly.

Washington University School of Medicine

Francisco was such a visionary and light in our field. We will deeply miss him. His kind approach, consummate devotion to his patients and families, and generous spirit brought so much progress and hope to his families and to all Alzheimer’s researchers—and other fields also—that his contributions and accomplishments will have enduring benefits for all of us. He trained and influenced many of us with his perspective, insight and thoughtfulness, that his legacy will continue through his many colleagues and mentees.

I was fortunate to have spent time with Francisco in Colombia, and learn from him. He always sought the best for his patients, families, and research participants. He ensured they would be taken care of, thinking holistically of their lives. Francisco’s warmth and sincerity were clear to everyone who knew him. I am one of many people fortunate to have known him.

Randy Bateman and Francisco Lopera.

From left to right, Susan Mills, Karina Skrbec, Laura Courtney, Russ Hornbeck, Ellen Ziegemeier, Jorge Llibre, Francisco Lopera, David Aguillón, Laura Ramírez, Yudy León, Marisol Londoño, Randy Bateman, all members of the DIAN and GNA teams, seen in November 2022 on a DIAN/DIAN-TU outreach visit to GNA in Colombia.

Neuroscience Group of Antioquia (GNA)

As translated from Spanish by Joseph Arboleda-Velasquez, I’d like to share my remarks at Dr. Lopera’s memorial service.

Dr. Francisco Lopera, my very dear friend for over 50 years, professor, and travel companion in the comings and goings of life and science, his invaluable contribution to the well-being of society was, is, and will continue to be the legacy of a lifetime dedicated to scientific research.

As a student, companion, and friend, I say with reverence and enthusiasm that he was a "master," a teacher in the true sense of the word, as an expression of excellence in daily work. He transmitted knowledge about the human being and taught us when and how to proceed with joy, in constant search of the truth.

Numerous generations of professionals have undoubtedly benefited from his teachings and felt the reassurance of his friendly hand as invaluable advice in everyday tasks.

He generously encouraged his disciples to remain in constant pursuit of knowledge. As disciples, we must understand that the best tribute one can pay to good people like Dr. Lopera is to imitate them.

He was aware of the economic, political, and cultural changes, of the transformations that society is undergoing, and the responsibility that this entails, as well as the need for family well-being.

Today, I want to repeat, thank you, many thanks, Dr. Lopera, for your respect and loyalty, for your joy, for your humility, for your dedication in your kind and responsible treatment of patients, for cultivating friendship, and much more transcendently—for your example of life.

Throughout this often-difficult journey of our lives, you gave us the presence of a one-of-a-kind being, whom we were lucky to know. A person whose very presence radiated peace, and with whom everyone who was by his side felt happy.

As long as we live, he will remain part of us.

Every word he spoke will be sealed on our lips. Every gesture he made will be etched in our memories. Every hug he gave us will remain forever in our bodies. Every loving glance he gave us will stay in our hearts. But above all, every silence we shared bound us forever.

There are no words to express what he has meant to so many people. There are only thousands of hearts filled with the love he gave us.

And that is why today I invite you to accompany him in his journey to the place that is rightfully his, with an applause so strong that it endures for years and years, resounding in the confines of the universe and wherever he may be.

Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School

I am very saddened by the passing of my dear friend, mentor, and collaborator, Dr. Francisco Lopera. It was a privilege to have him as my mentor for the past ~26 years. I owe so much of who I am today to his unwavering support. I will miss him deeply!

I joined Dr. Lopera’s group as a sophomore at the University of Antioquia after receiving a Colombian government research scholarship. From the start, Dr. Lopera took me under his wing and was deeply committed to my training as a “future researcher.” He initially assigned me to work with the Colombian families carrying the PSEN1 E280A mutation, which involved spending several days in rural Antioquia visiting patients and their relatives.

Later, he involved me in a collaborative project with Dr. Maria Antonieta Bobes from the Cuban Center for Neurosciences. I trained with Dr. Bobes during her visit to Colombia, and Dr. Lopera encouraged me to continue my training in Cuba. He helped me in raising the necessary funds to spend a semester there. The skills I acquired in Cuba laid the foundation for my first grant application ever, which proposed investigating brain changes using event-related potentials in individuals without symptoms from the Colombian kindred. I vividly recall how excited Dr. Lopera was about this proposal. He dedicated time to teach me how to translate my research ideas into a written proposal. We submitted the application to the University of Antioquia, and it was funded. This project became my undergraduate honor thesis and was later recognized by the Interamerican Society of Psychology as the best research conducted by an undergraduate student, leading to my first-author publication. None of this would have been possible without Dr. Lopera’s unwavering belief in my potential as a researcher. He went above and beyond to nurture my passion for science and was a key supporter of my nomination for this recognition.

About a year after I joined the group, I shared with Dr. Lopera my disappointment that the university did not have a neuroscience curriculum. I believed that many students were missing out on the chance to learn about neurosciences and his incredible work on Alzheimer’s disease. I proposed creating a student group focused on neuroscience training, and he immediately embraced the idea. With his full support, I launched “Sinapsis” (Synapse), a group designed to provide students with knowledge in neurosciences and opportunities to shadow or train with senior investigators like Dr. Lopera, Dr. Carlos Velez, Dr. Marlene Jimenez and others at the GNA. We initially started with college students, but soon expanded to include high school and even elementary students. Sinapsis reached its 25th anniversary in 2024, having successfully trained hundreds of students over the years. This achievement, too, would have been impossible without Dr. Lopera’s genuine enthusiasm for educating and supporting the next generation of researchers.

When I moved to Boston for graduate school, I told Dr. Lopera that I wanted to continue my research with the families for my master’s and Ph.D. work. I expressed interest in studying presymptomatic brain changes and shared that I was learning new neuroimaging techniques, including task-related fMRI. However, I was concerned that there was no fMRI research happening in Medellin. He simply replied, “Don’t worry, we will make it happen.” True to his word, we visited several MRI facilities in the city until we found one willing to collaborate on developing task-related fMRI. We started from the ground up, but thanks to a dedicated team effort, we pioneered this method in the city. The first studies, funded by my predoctoral NRSA and an internal grant from Boston University, marked the beginning of fMRI research with these families and provided some of the earliest evidence of measurable brain changes in presymptomatic individuals.

Since joining Dr. Lopera’s group in college, I have continued my work with him and the Colombian kindred without pause. The more time I spent with these AD families, the more I realized the importance of helping Dr. Lopera and others in the quest to find a cure for this devastating disease. Over the years, we have witnessed many family members suffer through the illness, feeling powerless to offer relief. Dr. Lopera showed me that while advancing research is crucial, it is equally important to care for patients and families and to give back to the community. He played a pivotal role in my decision to pursue a clinical degree in the U.S. as a clinical neuropsychologist, rather than remaining solely a cognitive neuroscientist. He often emphasized the importance of helping those already affected by the disease while continuing to advance our understanding and search for ways to prevent or stop its progression. From early on, he showed me the path forward. He also taught me the value of collaborating with people from different disciplines, working in partnership with patients, families, and the team of investigators, and sometimes taking risks if we truly want to make progress.

After I completed my Ph.D., he supported my application for a NIH DP5 Early Independence Award. I took a bold step by proposing to bring members of the Colombian families to Boston for PET imaging, which was not available locally. When I expressed my concerns about the logistics of bringing people to Boston monthly, once again, he reassured me not to worry, promising that he and his team at GNA would ensure the project’s success. This marked the start of the Colombia-Boston (COLBOS) biomarker study, which has provided significant insights into preclinical Alzheimer’s disease and its progression. Years later, while discussing “rare cases” from the API registry he had identified, I immediately proposed studying these cases and offered to write a grant for funding. He enthusiastically agreed, saying, “Oh yes, let’s write that one.” Thankfully, we secured funding from MGH and the Alzheimer’s Association, allowing us to launch the project I called “COLBOS Extreme,” which has led to the discovery of two protective mutations: APOE3 Christchurch and the Reelin-COLBOS.

It has been a profound honor to have Dr. Lopera in my life. Last year, I felt compelled to nominate him for the Potamkin Prize and I told him that, in my view, he was already deserving of a “Nobel Prize in Alzheimer’s disease.” I believed it was time for the world to acknowledge his significant contributions. I take great pride in having organized that nomination and am deeply grateful to Drs. Eric Reiman and Ken Kosik for supporting the nomination, as well as to the selection committee for recognizing him. The day he received the Potamkin Prize was the happiest I have ever seen him, and it was wonderful to witness his joy alongside his proud family. I’m so glad he received this well-deserved recognition while he was still with us.

Now it is our responsibility, as his mentees, to carry on his legacy by diligently advancing our understanding of dementias, seeking effective treatments, and offering compassionate care to patients and their families. One of his dreams was to create “Villa Aliria,” a place where training, research, clinical work, and care services could be seamlessly integrated. He began this project a few years ago and was very excited about it. I’m fully committed to supporting GNA in all its endeavors, including bringing this vision to fruition and ensuring it becomes a reality.

Gracias infinitas Dr. Lopera por tanto!! I will always be grateful. Thanks for inspiring so many of us and being such a great role model!

Global Brain Health Institute

I was honored to know Francisco Lopera as a collaborator, dear friend, and brilliant mind who profoundly influenced Latin American science. Working with him on numerous projects, including our ReDLat consortium, gave me an insight into his unwavering commitment to advancing brain health in our region. Francisco was more than a scientist; he was a figure of inspiration, fully immersed in supporting his community. His dedication to research and the well-being of those around him left an indelible mark on everyone fortunate enough to work with him.

One memory that stands out vividly is the annual meeting of REDLAT, hosted at Francisco's home (see picture attached). His house became a venue for collaboration, shared goals, authenticity, and trust. That atmosphere was rare—scientific rigor blended seamlessly with the warmth of community. His hospitality and genuine care brought us closer, creating a space where ideas flowed freely, and our shared passion for bettering brain health in Latin America became more vigorous. Francisco represented what Latin American science could aspire to. He was a living example of how to stay rooted in our culture yet push the boundaries of global research. His life’s work inspires countless people in the region to embrace their cultural contexts in scientific exploration, providing a model of elevating local research while having a global impact.

An extraordinary moment that comes to mind was our adventure to San Agustín in Colombia, one of the largest necropolises in the world in the middle of the mountains, to organize a conference on Brain Health. Francisco's enthusiasm for the rich history of his country was contagious. We explored the area, blending our love for science with the breathtaking landscapes of remote regions. But what truly brought the experience to life was our evening filled with dancing, particularly to the rhythm of Vallenato. Moments like this—surrounded by culture, history, and joy—defined our relationship and showcased Francisco's remarkable ability to merge his passion for Colombia with his love of science.

Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis

Francisco had a profound impact on my work and on the broader research community. He consistently fostered collaborations and pushed the boundaries of what was possible. He set the standard for engaging with and supporting families affected by neurodegenerative diseases in Latin America. As I collaborate with other PIs across the region through the DIAN-LatAm initiative, Francisco's work in Colombia remains a guiding example for us all. The DIAN-LatAm initiative was launched in 2019 as part of the broader DIAN with the goal of identifying new families in Latin America affected by dominantly inherited Alzheimer's disease and offering research opportunities, including experimental therapies aimed at prevention, delay, or treatment of Alzheimer's disease. DIAN-LatAm includes active sites for observational studies and clinical trials in Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, and Colombia.

Beyond his remarkable scientific discoveries and contributions to the field, what I appreciate most—and will always carry with me—is Francisco’s deep passion for improving the lives of families. His leadership opened doors for many important initiatives in Latin America, and his legacy will continue to inspire us for years to come.

Invonne Jimenez (Puerto Rico), Pablo Bagnati (Argentina), Francisco Lopera (Colombia), Jorge Llibre Guerra (USA), Ana Luisa Sosa (Mexico), Patricio Chrem (Argentina) (left to right), at the first DIAN-LatAm regional family meeting held in Mexico City in 2022.

Representatives from DIAN-OBS Latam site PIs and other Latin American countries working in the Genetic Counseling and Testing program for the DIAN-LatAm initiative surround Francisco Lopera.

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

I am very sad to hear of Francisco Lopera’s passing. Ken Kosik introduced me to Francisco because they wanted help in performing a genetic study in the families Francisco had identified. We collaborated for several years in the 1990s to identify the mutation causing disease in these large families and to better characterize the disease. At that time, we did not know if the families were linked genealogically and thus carried the same mutation. Several people visited my lab from Colombia, including Maribel Martinez, who worked in my lab for more than 15 years.

People from WashU also visited Dr. Lopera in Colombia, including postdoctoral fellow Dr. Corinne Lendon and a Chilean neurologist on the faculty at WashU, Dr. Lizzie Behrens. They both went with Dr. Lopera in the field to help collect samples and perform assessments, bringing blood/DNA samples back on the plane from Colombia for genetic studies.

Dr. Lopera was truly dedicated to helping the families and to finding the cause of disease in them so we could develop treatments. He was a devoted physician and scientist who made an outstanding contribution to our understanding of autosomal-dominant forms of Alzheimer's disease. He was also a warm and generous man, who will be sorely missed.

The photo at right is from around 1994, when Dr. Lopera visited us at WashU with his colleague Jorge Ossa.

Grupo de Neurociencias de Antioquia

The story behind a Master …

When I arrived at Neurosciences Group at the University of Antioquia, in the early 2000s, I was in my fifth semester of medicine. I met Francisco Lopera at a presentation and felt like the world had opened up to me, and I said I wanted to one day explain Alzheimer's disease as clearly as he did. It was a time when the existence of MCI was still in doubt, and the best way to demonstrate the preclinical stages were the autosomal-dominant variants, he said.

So, we went through the municipalities of Antioquia with identified families to update the genealogies and clinical data. I was studying epidemiology, and the fundamental question was what is the age of onset of familial Alzheimer's disease by PSEN 1 E280A mutation? To start developing medications, he told me, evaluating healthy offspring was the priority. I understood that later.

He never missed a “commission,” that's what we called field work. In one of the hamlets we visited, he even tried to stop a fight between one of the patients and another neighbor. We all ran away, except him. At night we went dancing, but we had to get up early the next day. And he was always ready from 7 a.m. when we started the talks with the families and then the medical and neuropsychological evaluations.

The evaluations were usually in nearby hospitals, community halls, or schools in the villages. But also in the houses, next to the patient. He did the genealogy and asked questions; I wrote and did the medical and neurological exam. Practicing psychologists, a nurse and a gerontologist joined together at that time. No more than five to six people.

At that time, diapers and wheelchairs were more useful to people than any other medicine. And unfortunately, it is still the same. And that is why the “Social Plan” was the condition he set for starting any clinical trial in these families. We all danced, sang, made crafts with the patients and caregivers in these social spaces, including him. The E280A families are our families, and even more so after eight years of follow-up with the clinical trial with crenezumab that began in 2013. Because getting involved with them, week after week, strengthened ties beyond the doctor-patient relationship. That was taught to us by Lopera.

He always defended the idea that if one day, a drug tested in this population shows effectiveness, the families of Colombia should be compensated. The thousands of patients in Colombia who saw in him the face of hope remind us of a worldwide desire: a modifying drug that can also be distributed with equity and justice. Pillars in his life and work.

We are now continuing his charge, and when I say we, I am not only referring to his students and all the members of the Neurosciences Group at the University of Antioquia. Because his legacy crossed borders. The time and work that remains for us will show that more than half of his life dedicated to Alzheimer's will not have been in vain.

Newcastle University and University of Nairobi, Kenya

Colleagues and friends including Joe, Diego, and Ken, who knew Francisco better than I did, have already given wonderful accounts of his life and times. I echo those sentiments and reminisces, and indeed it was an honor and privilege to know Francisco Lopera. Some years ago Francisco was at the World Federation of Neurology congress in Santiago (photo) with some of the giants of the dementia research world. It was obvious then, Francisco was relishing his profound successes and contributions to better understanding the prognosis and progression of familial AD caused by the E208A mutation in PSEN1. Despite the very human character we might all display at times, I believe Francisco is remembered as a scholar, gentleman, and bon viveur. He played many roles professionally as a local doctor, administrator, epidemiologist, neurologist and neuroscientist, and a notable brain banker!

He was a mentor, teacher, a colleague, and friend to many. His noble work and passion to elucidate the reasons behind memory problems in a large number of the Colombian families in the Paisa region of Medellin is par excellence. This is especially worthy of note because originating from the LMICs, with often poor-resource settings, he forged strong links with North America. I think the lesson to learn for our trainees and younger colleagues, especially those from the LMICs, is to discern a worthy question and then follow to find the answer(s) with your heart. Even in these days of austerity and shortage, money and support will eventually pour in.

We longed to have Francisco at our quadrennial (and recently switched to biennial) Dementia in LMICs symposia in Kenya but this was not to be. According to a close friend Francisco was also looking forward to an adventurous African safari. Like said of other friends who have passed away in recent months, it will take some time for the reality to sink in that Francisco will no longer be with us in person, although he will be in our memories for as long as we live.

Francisco Lopera with Vladimir Hachinski, Raj Kalaria, Gustavo Roman, and Alna Gonzalez Quevedo (right to left) at the 2015 World Federation of Neurology Congress, Santiago, Chile.

International Group of Neuroscience, Neuroengineering and Neurophilosophy IGN(S,E,P)

My research with Dr. Francisco Lopera has been intermittent, unconventional, and independent, but long-lasting and deep. I first met him in the late '80s, one Friday afternoon before his weekly meeting with the interdisciplinary “aphasia group” at the Hospital San Vicente de Paul. This group included physicians, phono-audiologists, linguists, and psychologists, and was coordinated by Claramonika (later Dr. Lopera’s wife) and Francisco.

My father had told me about many researchers at the University of Antioquia. At the time, I was working on my bachelor of science thesis in electronic engineering, focusing on mathematical models of neurocircuits. Claramonika and Dr. Lopera did not see me as a crazy student lost in unpractical fields far from my training. Ignacio Escobar Mejia, a true pioneer, was an electrical engineer and the director of my thesis. He was also a professor of physiology, and Dr. Lopera was his student. Instead of disliking it, Dr. Lopera and Claramonika enjoyed the interdisciplinary nature of my work.

met other people in his group whom I had known from other circles, such as the neurologist, warm researcher, and intellectual David A. Pineda, a long-term friend of Dr. Lopera, who also published poetry books. Dr. Lopera’s group was studying aphasia from all possible perspectives! When I finished my bachelor's thesis in 1986, Dr. Lopera discussed it with me. The technical language did not make him uncomfortable. He was excited about my comments on postmortem studies of Einstein’s brain and asked me for more references. He was curious about how it related to Einstein’s conception of a four-dimensional universe. I was surprised by his friendly interest in these exotic and purely theoretical issues. Studying the brain in this way was considered impractical at the time, especially if one wanted a lucrative career.

Although I did not consider myself suitable for the “big leagues of science,” I decided to follow, in a humble way, the example of Einstein: to keep working on the brain in my free time. Empowered by Dr. Lopera’s encouragement (“Nothing is impossible for those who want it,” he used to say), I nurtured romantic dreams: Perhaps this would be a more genuine and independent path, an opportunity to follow my own dream. I got a conventional job and stopped attending Dr. Lopera’s group, but I remained fascinated by the jungle of neural networks, where some researchers, as Cajal said, have lost their soul.

The seed for conducting rigorous theoretical research on the brain was growing, not only within me but globally. The Decade of the Brain was inspiring, and neuroscientists were becoming more open to realistic mathematical models. Dr. Lopera’s group identified the genetic cause of familial Alzheimer’s disease in Antioquia. An electrical approach to the brain, the EEG, was showing exciting potential by recording gamma activity. Additionally, our esteemed Colombian neuroscientist, Dr. Rodolfo Llinás at NYU, published his proposal about the 40 Hz sweep across the brain based on magnetoencephalography.

Excited by all this, I reconnected with Dr. Lopera. Driven by spontaneous enthusiasm, I proposed research that combined new ideas I had developed over the years about my bachelor's of science thesis model of interhemispheric communication with his and Dr. Llinás’ research on Alzheimer’s disease, 40 Hz, and thalamo-cortical interactions*. In 1997, we traveled to Houston for the neural network conference, where we received a warm welcome from physicist John G. Taylor and a somewhat skeptical attitude from Dr. Karl Pribram. Dr. Pribram, renowned for his pioneering work on the holographic theory of brain function, brought a unique perspective to our discussions. His skepticism was a reminder of the rigorous scrutiny that innovative ideas must endure, ultimately enriching our understanding and pushing the boundaries of neuroscience. These were exciting times, as we searched for electrophysiological correlates of consciousness in health and disease (e.g. AD), as described by Dr. Taylor in his book “The Race for Consciousness.”

I was eager to publish these ideas from a purely scientific perspective. Dr. Lopera, however, had a more mature attitude. His experience with patients and devastating diseases like Alzheimer’s made him prioritize alleviating human suffering over pure scientific passion, although that passion was also strongly present in him.

I can describe other research we did together and how supportive he was with new ideas and proposals. He had his home and consulting room for his private practice a few blocks from my home, where he helped patients in the afternoon. Our relationship was not limited to the university; I often visited him at his personal office in the afternoons.

In my search for my own dream, I disconnected from Dr. Lopera for many years. I contacted him again a few weeks ago by email, and he was going to give me “a signal” when he had time. Perhaps the signal will not be what we expected.

Dr. Lopera, the human being who, without saying a word, inspired me to have big dreams in neuroscience, was probably telling me, again, “Nothing is impossible for those who want it.” Thank you, Dr. Lopera. What is the sea of death according to the God of Goethe, the one in which you believe? I’m not sure, but from the invitation to your funeral from the members of your group GNA, I learned that, after all, this sea can be seen with love when contemplated from that special temple you were silently constructing, not on the beach or the mountain, but in our hearts.

This message was sent to me by the GNA to call for the funeral ceremony: “La muerte deja en claro que solo el amor importa, que solo el amor hace que la vida valga la pena y que todo lo demás es polvo”—Death makes it clear that only love matters, that only love makes life worth living and that everything else is dust. —Jeff Foster

* We proposed that thalamic oscillators, particularly in the intralaminar nucleus, are crucial for interhemispheric communication. This concept aligns with our 1999 paper, which presented a topological hypothesis for the functional connections of the cortex. In this later work, we suggested that the brain’s functional connections could be understood through principles of cortical graphs based on EEG and neuroimaging data. Both studies emphasize the importance of neural oscillations and topological frameworks in understanding brain connectivity, which is particularly relevant for exploring disruptions in 3 neural network states (activated, inactivated, pre/semiactivated) seen in conditions like Alzheimer’s disease.

Florida Atlantic University

I met Francisco, whom we affectionately call Pacho, in the 1980s when he did a residency in neuropsychology at the Neurological Institute of Colombia in Bogotá under the mentorship of Alfredo Ardila, my deceased husband. In the 1990s and in the years 2000 and 2001, I collaborated with Francisco on several research projects, scientific articles, and one neuropsychology book in Spanish; at the time we were both active members of the Colombian Society of Neuropsychology. From 1999 to 2023, I participated with him in diverse activities of the Asociación Latinoamericana de Neuropsicología (Latin American Association of Neuropsychology, ALAN), of which he was a founding member.

I have always admired not only his intelligence and originality but also his academic generosity, his humility, and great sense of humor. On numerous occasions, I joined him and other members of the ALAN, including Alfredo Ardila, in academic discussions on the future of neuropsychology in Latinoamerica. Pacho was not only a great colleague but a fantastic friend who will be deeply missed.

His passing has hit me and the other members of ALAN very hard. It is a great loss for science in general and, in particular, for Latin American neurology and neuropsychology. My deepest condolences to his wife Claramonika and his daughter Karina. PACHO, TE VAMOS A EXTRAÑAR MUCHÍSIMO.

Rosselli, M., & Ardila, A. (1986). Alteraciones de la lectura, la escritura y el cálculo (Reading, writing, and calculation disorders). In: J. Bustamante, F. Lopera, & J. Rojas (eds). El Lenguaje: Perspectivas en Neurolingüística (Language: A Neurolinguistic Perspective) Medellín: Prensa Creativa, pp. 273 280.

Rosselli, M., Ardila, A., Pineda, D., & Lopera, F. (1997). Neuropsicología Infantil (Child Neuropsychology). Medellín (Colombia): Editorial Prensa Creativa, 2nd Ed.

Lopera, F., Ardila, A., Martinez, Al., Madrigal, L., Arango Viana, J.C., Lemere, C., Arango Lasprilla, J.C., Hincapie, L., Arcos, M., Ossa, J.E., Behrens, I.M., Norton, J., Lendon, C., Goates, A., Ruiz Linares, A., Rosselli, M., & Kosik, K.S. (1997). Clinical features of early-onset Alzheimer's disease in a large kindred with an E280A presenilin 1 mutation. JAMA, 277, 793 799.

Lopera, F., Ardila, A. , Rosselli, M., Moreno, S. , & Arango- Lasprilla, J.C. (1999). Perfil Neuropsicológico de una Extensa Familia con Enfermedad de Alzheimer Familiar causada por la mutación E280A de la presenilina 1. Spanish National Conference on Alzheimer’s Disease. Bilbao, Spain.

Ardila, A., Lopera, F., Rosselli, M., Moreno, S., Arcos, M., Madrigal, L., Arango, J.C., Tobon, N., Arango Viaja, J.C., Ossa, J., Lendon, C., Goate, A., & Kosik, K. . (2000). Neuropsychological profile of a large kindred with familial Alzheimer’s disease-associated to single presenilin 1 mutation.

Rosselli, M., Ardila, A., Moreno , S., Standish, V., Arango-Lasprilla, J.C., Tirado, V., Ossa, J., Goate, A.M., Kosik, S., & Lopera , F. (2000). Cognitive decline in patients with familial Alzheimer’s disease associated with E280A presenilin- 1 mutation: a longitudinal study.

Johnson, K., Lopera, F., Jones, K., Becker, A., Sperling, R., Hilson, J., Londoño, J., Siegert, I., Arcos, M., Moreno, S., Madrigal, L., Ossa, J., Pineda, N., Ardila, A., Rosselli, M., Albert, M., Kosik, K.S., & Rios, A. (2001). Presenilin-1-Associated Abnormalities in Regional Cerebral Perfusion.

AC Immune SA

I was extremely saddened by the news that Francisco had passed away. I recall us saying goodbye to each other at the AAIC meeting in Philadelphia only a few weeks ago.

He was such a magnificent inspiration to anyone working in the field of Alzheimer’s disease. His integrity, intellect, compassion, and overwhelming focus on his patients and their care were characteristics which drove him to always strive for delivering real clinical benefit to them, despite the challenges of the disease, the location, and the often humble lives of those affected.

Our long-standing collaboration around the API-ADAD study was an example to us of what can be achieved when people come together in a determined and respectful way to make a difference through rigorous application of science and medicine.

We will miss his enthusiasm and his dedication to improving the outlook for everyone impacted by Alzheimer’s disease. On behalf of the whole AC Immune team, our sincere condolences to his family and many friends.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.