Meet medRχiv: A New Preprint Server for Health Research

Quick Links

Today the co-founders of the preprint server bioRχiv, together with The BMJ in London and Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, launch a sister repository for research papers in the medical sciences. Called medRχiv, this free, nonprofit service run by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, New York, will accept health-related articles and clinical trial papers before they go through peer review.

- The new preprint server medRχiv publishes health-related papers ahead of peer review.

- Built-in safeguards aim to protect public health, clinical practice.

- Some researchers are still skeptical about releasing preliminary health research publicly.

As a counter to that often long and arduous process, preprint servers have been around for decades in physics, mathematics, and life or social sciences. They have been slow to catch on in the medical field, where data are arguably more consequential—and potentially dangerous—for public health. The creators of medRχiv believe the new server will allow clinician-researchers to share their results once manuscripts are complete, and not have to wait months and sometimes years to publish in peer-reviewed journals. “Many clinical scientists, knowing how useful bioRχiv is proving to be in the biological sciences, wanted to see a similar initiative for their discipline,” said co-founder John Inglis of Cold Spring.

“The hope is that medRχiv can speed up sharing of clinical trial results in a manner that benefits the field,” said Murali Doraiswamy, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina. “The downside is that if clinical research results are not well vetted, then they can harm people.”

MedRχiv will function much like bioRχiv, but will specifically host health-related research, including clinical trials. Like bioRχiv, medRχiv will allow negative, confirmatory, or inconclusive results—data that are hard to publish in journals—in addition to research and data articles. It will also accept several article types not accepted on bioRχiv: systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and clinical research design protocols. Like bioRχiv, it won’t accept case reports, narrative reviews, editorials, letters, or opinion pieces. Categories span 51 subject areas, including genetic and genomic medicine, neurology, radiology, imaging, pathology, and geriatric medicine.

These 51 categories will replace two clinical subject categories that were being piloted on bioRχiv: clinical trials and epidemiology. With the advent of medRχiv, bioRχiv will reroute submissions in those areas to medRχiv.

David Maslove, a clinician scientist at Kingston General Hospital, Ontario, Canada, shared Doraiswamy’s concerns. “Medicine is inherently different from something like particle physics,” he said. “There’s greater public interest in studies about clinical trials, health, and medicine because people are curious about their own health.” Patients search for and sometimes act on new information about treatments, and medical studies are easier to understand than more complicated scientific studies, making health-related preprints more liable to mislead the public, he said.

David Knopman, Mayo Clinic, Rochester Minnesota, agreed, particularly regarding clinical trial manuscripts. “I worry about non-peer-reviewed articles that have therapeutic or diagnostic implications,” he wrote to Alzforum. “If claims about diagnosis or therapy are not vetted by peer review, I could see utter disaster in the clinical world.” As an editor and reviewer, Knopman has encountered overstated assertions of effectiveness numerous times. “If those claims had made it into what is considered legitimate medical literature, the sponsors—both academics and corporate sponsors—would have been empowered to make false claims of efficacy,” he said.

In response to such concerns, Inglis and his Cold Spring co-founder Richard Sever have put in more safeguards and screening procedures than on bioRχiv, including review by an editorial team. “We recognize that there are potential risks, but feel those could be mitigated by adopting appropriate measures,” Inglis wrote to Alzforum.

Building on the bioRχiv Model

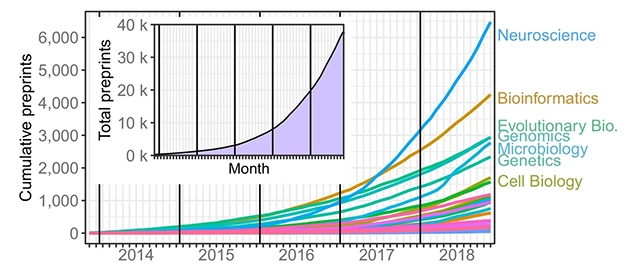

MedRχiv follows on the runaway success of its forerunner, bioRχiv, the life-sciences preprint server. After it debuted in November 2013, bioRχiv generated fewer than 100 submissions per month for the first year. Fast-forward to 2019, and the rate has risen exponentially. In May alone, 2,508 articles were posted. In total, upwards of 52,000 manuscripts have gone up on bioRχiv. This past March, they were downloaded almost 1.7 million times. Papers on Alzheimer’s disease have followed that same trajectory. To date, 3,494 have appeared on bioRχiv. Just 27 went up in 2014, growing to 1,427 in 2018. For 2019, 1,097 papers are already posted. Notably, the category most often submitted and downloaded is neuroscience (see image below).

Neuroscience Leads the Way. As of October 2018, almost 40,000 preprints were posted on bioRχiv (inset). Most papers were in the neuroscience category. [Courtesy of Abdill and Blekhman, 2019.]

Scientists were once wary of releasing preprints before publication for fear of interfering with eventual publication in a peer-reviewed journal. However, there is little evidence of that. Richard Abdill and Ran Blekhman at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, have analyzed the first five years of uploads to bioRχiv (Abdill and Blekhman, 2019). They reported that two-thirds of posted papers have been published in peer-reviewed journals. Of those, 75 percent were published within eight months. These include papers on AD. A paper on CRISPR editing of Alzheimer’s disease genes by Subhojit Roy and colleagues at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, was downloaded from bioRχiv 1,131 times and appeared in Nature Communications within the year (Sun et al., 2019). Alzforum has covered 18 bioRχiv papers since 2017, and eight have already appeared in peer-reviewed journals. For example, two meta-analyses of Alzheimer’s GWAS studies garnered 2,529 and 4,395 downloads from bioRχiv, respectively, and were published in Nature Genetics (see Apr 2018 news on Kunkle et al., 2018, and Jansen et al., 2018).

Inglis attributes the rise of preprint servers to their ability to pick up the pace of research and increase transparency. Anyone can immediately see the data and use it to guide their own research, he said. “We have lots of anecdotal evidence from authors who saw a preprint, assessed its value, incorporated its findings, and pushed on with their own work long before the preprint was published,” he wrote to Alzforum.

Researchers can also share their work widely, allowing others to evaluate and provide feedback both within and outside of bioRχiv. This fosters faster communication and helps authors improve their manuscript for peer review, Inglis said. Roy tweeted that his CRISPR paper on bioRχiv got him at least three talk invitations.

Forging New Ground

MedRχiv’s screening resembles a form of peer review. It involves a multistep process managed by Inglis, Sever, Harlan Krumholz and Joseph Ross, both at the Yale School of Medicine, and Theodora Bloom and Claire Rawlinson at The BMJ. Authors must indicate that they have followed ethical guidelines, obtained consent from participants, and registered clinical trials on an internationally recognized registry, such as Clinicaltrials.gov or the EU Clinical Trials Register. They must also declare competing interests and provide a funding statement.

After an automated plagiarism check, an in-house screening team at Cold Spring will take a first pass at the manuscripts. They will reject papers they consider defamatory, promotional, or a threat to patient privacy. Approved papers will go to one of several dozen volunteer scientists, clinicians, and editors, who will scrutinize each submission. If any public-safety concerns are raised, the managing editors will review the paper and make a final decision. For example, manuscripts that question the safety of vaccines, describe infectious agents that could be used in biological warfare, or that would likely lead people or clinicians to change drug regimens will be carefully vetted. “Our screening process asks: ‘If this paper’s claims or conclusions are wrong, could it realistically cause significant harm to an individual or population?’” Inglis said. If the answer is yes, authors will be advised to publish in a peer-reviewed journal.

While stringent, the medRχiv screening process differs from traditional peer review. “There is no assessment of the quality or novelty of the research, the validity and accuracy of the analysis, or the strength of the conclusions drawn,” Inglis told Alzforum. Each posted manuscript will be labeled as “not peer reviewed,” and will carry an advisory that it should not be used to inform medical treatment or be reported in the press as a medical advance.

Maslove welcomes the safeguards; however, on balance he argued it would be better to fix the problems inherent in the peer-review system rather than bypass it altogether. After all, some manuscripts are substantially altered or rejected by peer review, and rightly so. “If we dedicated more resources to peer review and properly rewarded it, then perhaps more people would get engaged and that would speed up the process,” Maslove said.

This is not the first preprint server for medical research. The BMJ started ClinMedNetPrints.org in 1999, but only 80 papers were submitted in 10 years, and it shut down in 2008. Last year, The Lancet started its own preprint service (Kleinert et al., 2018). As is the case with Cell Press’ Sneak Peek, another preprint server in basic science, authors submitting to The Lancet have the option to post publicly during peer review. Rawlinson and Bloom believe the community at large may be better served by a central archive that is not linked to a specific journal (Rawlinson and Bloom, 2019).

“I’m curious to see how this will play out,” said Lon Schneider, University of Southern California, Los Angeles. “I generally think wider disbursement is a good thing.” At the same time, he said there’s always the potential—as there is in peer review—for unjustified claims to be made and outcomes spun.—Gwyneth Dickey Zakaib

References

Paper Citations

- Abdill RJ, Blekhman R. Tracking the popularity and outcomes of all bioRxiv preprints. Elife. 2019 Apr 24;8 PubMed.

- Sun J, Carlson-Stevermer J, Das U, Shen M, Delenclos M, Snead AM, Koo SY, Wang L, Qiao D, Loi J, Petersen AJ, Stockton M, Bhattacharyya A, Jones MV, Zhao X, McLean PJ, Sproul AA, Saha K, Roy S. CRISPR/Cas9 editing of APP C-terminus attenuates β-cleavage and promotes α-cleavage. Nat Commun. 2019 Jan 3;10(1):53. PubMed.

- Kunkle BW, Grenier-Boley B, Sims R, Bis JC, Naj AC, Boland A, Vronskaya M, van der Lee SJ, Amlie-Wolf A, Bellenguez C, Frizatti A, Chouraki V, Alzheimer's Disease Genetics Consortium (ADGC), European Alzheimer's Disease Initiative (EADI), Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology Consortium (CHARGE), Genetic and Environmental Risk in Alzheimer's Disease Consortium (GERAD/PERADES), Schmidt H, Hakonarson H, Munger R, Schmidt, Farrer LA, Broeckhoven CV, O'Donovan MC, Destefano AL, Jones L, Haines JL, Deleuze JF, Owen MJ, Gudnason V, Mayeux RP, Escott-Price V, Psaty BM, Ruiz A, Ramirez A, Wang LS, van Duijn CM, Holmans PA, Seshadri S, Williams J, Amouyel P, Schellenberg GD, Lambert JC, Pericak-Vance MA. Meta-analysis of genetic association with diagnosed Alzheimer's disease identifies novel risk loci and implicates Abeta, Tau, immunity and lipid processing. bioRxiv. April 5, 2018. bioRxiv.

- Jansen I, Savage J, Watanabe K, Bryois J, Williams D, Steinberg S, Sealock J, Karlsson I, Hagg S, Athanasiu L, Voyle N, Proitsi P, Witoelar A, Stringer S, Aarsland D, Almdahl I, Andersen F, Bergh S, Bettella F, Bjornsson S, Braekhus A, Brathen G, de Leeuw C, Desikan R, Djurovic S, Dumitrescu L, Fladby T, Homan T, Jonsson P, Kiddle S, Rongve A, Saltvedt I, Sando S, Selbak G, Skene N, Snaedal J, Stordal E, Ulstein I, Wang Y, White L, Hjerling-Leffler J, Sullivan P, van der Flier W, Dobson R, Davis L, Stefansson H, Stefansson K, Pedersen N, Ripke S, Andreassen O, Posthuma D. Genetic meta-analysis identifies 9 novel loci and functional pathways for Alzheimers disease risk. bioRxiv. February 22, 2018. bioRxiv.

- Kleinert S, Horton R, Editors of the Lancet family of journals. Preprints with The Lancet: joining online research discussion platforms. Lancet. 2018 Jun 23;391(10139):2482-2483. PubMed.

- Rawlinson C, Bloom T. New preprint server for medical research. BMJ. 2019 Jun 5;365:l2301. PubMed.

Other Citations

Further Reading

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.