Robert D. Terry, 93, Co-Founder of U.S. Alzheimer’s Research

Quick Links

On May 20, at age 93, Robert Davis Terry passed away in Carlsbad, California. Terry had been in declining health for some time, according to Michael Shelanski of Columbia University, New York, an early trainee and longtime friend. During Shelanski’s last dinner visit with Terry, in 2016, Terry was discussing neuropathology and recent events. “He was interested in everything, but had become frail,” Shelanski said. Many of Terry’s trainees stayed close with him and made “pilgrimages” to Carlsbad after Terry retired in 1994.

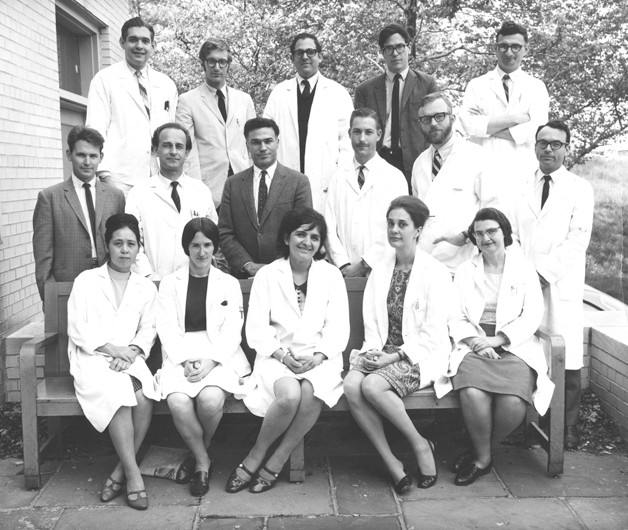

[Courtesy of Mary Sundsmo.]

Terry made his mark in Alzheimer’s research in the 1960s, soon after leaving Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx, New York, to join the pathology department at Albert Einstein College of Medicine under Saul Korey. Terry trained two generations of neuropathologists working in the field of neurodegeneration, including, among many others, Bernardino Ghetti, Richard DeTeresa, Dikran Horoupian, James Goldman, Roy Weller, Robert Murray, Kinuko Suzuki, Larry Hansen, and Dennis Dickson, who published a tribute to Terry 12 years ago (Dickson, 2005).

Already looking beyond pathology at that time, Terry formed multidisciplinary research teams right away. He recruited basic scientists such as Henry Wisniewski from Poland, Peter Davies from the U.K., Khalid Iqbal, and others to enable broad-based research on neurologic disease from all available scientific angles. “Bob worked closely with people who were cell biologists and biochemists at a time when most neuropathologists only looked at tissue. He was a nucleating force in the field,” Shelanski told Alzforum. Terry obtained the first NIH grant on Alzheimer’s disease, according to Zaven Khachaturian, and he held on to it for more than 30 years.

Top row, from left: Steven Shayvitz, Michael Shelanski, Richard Snyder, John Prineas, Carlos Araoz. Middle row, from left: Roy Weller, Henryk Wisniewski, Robert Terry, John Andrews, Jan Leestma, Ivan Herzog. Seated, from left: Kinuko Suzuki, Marlene Lengner, Krystyna Wisniewska, Kytja Voeller, and Anne Johnson. Of these people in Terry’s lab in 1968, Suzuki, Wisniewski, Johnson, Weller, and Shelanski worked extensively in Alzheimer’s disease. [Courtesy of Michael Shelanski.]

Early on at Einstein, Terry applied electron microscopy to the study of neurologic disease, characterizing first the ultrastructure of Tay-Sachs disease and then of AD. His images were so striking that New York City’s Museum of Modern Art included one on Tay-Sachs in a 1967 exhibition called “Once Invisible” (view image in the Photo Gallery at bottom of page on university website; item 78 in MoMA’s press release).

In Alzheimer’s disease, Terry and colleagues conducted electron microscopy and histochemical analyses of both amyloid plaques and the paired helical filaments that make up neurofibrillary tangles. “They realized very early on that AD had unique structures,” Shelanski said. “Bob performed the most detailed and sophisticated ultrastructural studies of plaques and tangles … utilizing the most advanced technology at the time,” Eliezer Masliah, now at National Institute on Aging, wrote to Alzforum (see full comment below).

Shelanski also remembers “hilarious times” in his early years with Terry, such as a period in 1966, when Terry’s friend, the late British neurologist Oliver Sacks, worked in the lab after finishing medical school at Oxford. “Oliver used to show up with a big beard and his motorcycle helmet, and Bob soon decided lab work was not Oliver’s forte,” Shelanski said. A newspaper profile of Sacks, who went on to become a revered diagnostician and writer, dryly notes a hamburger in a centrifuge and cheerfully cites Terry’s appraisal of Sacks’ lab work as being “an absolute disaster” (The New York Times, 1991).

The two Bobs (Terry and Katzman). [Courtesy of Mary Sundsmo.]

Also at Einstein, Terry focused the attention of Robert Katzman, who at the time was studying the blood-brain barrier, toward Alzheimer’s. From then on, the two Bobs collaborated closely. This led to their realization, in the mid-’70s, that dementia in old people was the common form of Alzheimer’s disease. Until then, AD had been considered a rare pre-senile condition, and age-related dementia a cerebrovascular problem (see Research Timeline).

Bob Terry's lab in 1990 at UCSD. From left: Rich DeTeresa, Larry Hansen, Ellie Michaels, Terry, Eliezer Masliah, Margaret Mallory, Michael Alford (research associate). [Courtesy of Eliezer Masliah].

After 30 years in New York, Terry followed Katzman to the University of California, San Diego, to lead the neuropathology core at the newly inaugurated Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, which Katzman was directing. This was one of five founding centers with which the NIA started its centers program (Oct 2014 news). At UCSD, Terry focused first — along with DeTeresa, who had moved out from Einstein — on developing a method to count neurons in the aging human cortex in AD in order to document neuronal loss in AD. He also trained, among others, Larry Hanson and Masliah. With Hanson, he described the Lewy body variant of AD. Later, using synaptophysin immunohistochemistry paired with confocal microscopy in postmortem AD brain, he and Masliah showed that synapse loss correlates more tightly with cognitive decline than amyloid plaques do (Research Timeline).

Among other honors, Terry won the inaugural Potamkin Prize for Research in Pick’s, Alzheimer’s, and related diseases in 1988, and in 1990, the MetLife Foundation’s Award for Medical Research in Alzheimer’s Disease.

In 1994, Terry accepted a retirement buyout from the University of California, but according to his UCSD faculty page, he kept visiting the lab daily for many more years. “He constantly told me that he regretted having retired,” said Shelanski. To peruse Terry’s notable papers, see here and here.

In 2006, Terry spoke, indeed entertained the crowd, at the Alzheimer Centennial conference, held in Tuebingen, Germany, in the same auditorium where Alois Alzheimer had first presented the case of Auguste D to his colleagues at the time (Nov 2006 news).

Robert D. Terry was born in 1924 in Hartford, Connecticut. He started premed studies at Williams College, but after the Pearl Harbor attack left school to join the Army 82nd Airborne Division paratroopers. Terry went on active duty in 1943, at age 19, and later parachuted into the Battle of the Bulge on the war’s Western front, in the Ardennes region. “Throughout his life, he felt a great closeness to anyone who had also been a paratrooper,” Shelanski told Alzforum. After the war, Terry got rejected by numerous medical schools before graduating from Albany Medical College.

Terry was courteous, strikingly good looking, and tough. Shelanski recalled a pathology meeting near Yale in the late 1960s, where their session ran too long in a small room off a big ballroom. A wedding was going on in the ballroom, and the bride was clearly from a mafia family, Shelanski said. In front of the doors were two large men who were there to make sure there would be no disturbance. “When we tried to leave our room, they blocked us. Bob was a short guy. He went right up to them and said, ‘I am coming out now.’ They let us out,” Shelanski said.

Terry had a reputation for pulling no punches in discussions and at conferences. “If someone got up and asked a question, and Bob’s voice grew louder and his face got a little red, you knew the person would have a hard time defending their question,” said Douglas Galasko, who joined UCSD two years after Terry and collaborated with him there. “Bob was mercurial and could scorch anybody,” Shelanski agreed, adding “At 44, he was told he had hypertension and had to control his temper. And he did.”

Terry is survived by his son, artist Nick Terry, of Marfa, Texas.—Gabrielle Strobel

References

News Citations

- At Birthday Symposium, Massachusetts ADRC Looks to Future With New Data

- Tuebingen: Researchers Reminisce, Predict at Alzheimer Centennial

Paper Citations

- Dickson DW. A tribute to a neuropathologist, Robert D. Terry. Alzheimers Dement. 2005 Jul;1(1):74-6. PubMed.

Other Citations

External Citations

Further Reading

No Available Further Reading

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

Bob Terry was a loving father and husband, veteran of WWII, animal enthusiast, admired mentor and teacher, and pioneer of the modern era of neuropathology of neurodegenerative disorders. At a time when diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Pick’s were little known, Bob Terry, in collaboration with Bob Katzman, was among the first in the 1960s and ’70s to bring renewed interest to the study of AD and related neurodegenerative disorders.

Bob was very interested in understanding the nature of the filamentous aggregates accumulating in neurons and in the extracellular space, utilizing biopsies from patients with Alzheimer’s. As faculty at Einstein, he performed the most detailed and sophisticated ultrastructural studies of plaques and tangles in Alzheimer’s disease, utilizing the most advanced technology at the time.

When I joined Bob Terry’s laboratory at UCSD in 1988, he gave me the great opportunity to work on these unexplored and mysterious neurodegenerative disorders. We worked together for several years, until he retired in 1994, at better understanding how synaptic damage contributes to the cognitive impairment in AD. Even after retirement Bob continued working, attending the laboratory at UCSD and scientific meetings challenging the field with new concepts and ideas. In 1989, Bob Terry received the Distinguished Service Award from the American Association of Neuropathologists, and he was a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Global R&D Partners, LLC

I first met Bob Terry as a medical student at Einstein. I met Leon Thal, Bob Katzman, Peter Davies, Dennis Dickson, Joe Masdeu, and Howard Crystal at Einstein as well. These mentors had a big impact on my decision to further study AD. My years at Einstein were very exciting, as AD was just being recognized as a major cause of dementia and there was so much to learn about it.

It was great to attend conferences there and to hear the researchers discuss their latest findings. One could always count on Bob Terry to get up at these meetings and make a comment. He was passionate about the science and loved to argue about it. Bob was always very friendly to me and I enjoyed speaking with him and learning from his insights.

Alzheimer's & Dementia

Robert Davis Terry, M.D., was a giant in dementia-Alzheimer’s disease research. He pioneered the launch of the modern era of systematic studies on these neurodegenerative diseases. His passing marks a significant event in the history of the Alzheimer movement; he will be missed but not forgotten.

Bob’s intellectual and scientific legacy is already immortalized and will continue to flourish through the worldwide contributions of innumerable colleagues, collaborators, postdoctoral fellows, and students whom he mentored. Bob Terry influenced, one way or another, the scientific careers of a very large number of the key opinion leaders in dementia research.

This short statement is inadequate for a full and more fitting tribute to this great physician scientist; a more extensive celebration of this fallen warrior’s many contributions to our field is in preparation in the journal Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

I will always remember the time Bob Terry told me about his belief that serendipity plays a huge role in science, and how exciting it was to do the first EMs of human brain—something that he seemingly ended up doing almost by chance. Everything he saw was being seen for the first time; his excitement about that was palpable, even though it was 20 years later when we had this discussion. A pioneer in every sense, Bob was a clear thinker, a champion of science, and a great mentor to his colleagues and friends. He will be deeply missed.

I worked at Glenbrook in Carlsbad, where Dr. Terry resided, and had the pleasure of helping to care for him over the last year. In his own way, Dr. Terry was a wonderful mentor and has inspired me to consider pursuing AD research in the future. As an incoming first-year student starting medical school this summer, I will reflect fondly on the times I spent talking with Dr. Terry.

Here, for my late father’s many friends, and the Alzheimer’s research community at large, I offer a few more details about his life. After growing up in the Hartford area, dad studied chemistry and biology at Williams, along with literature, art history, and economics. Three months into his first semester, war was declared and he immediately enlisted. As a member of the Army Enlisted reserve, he went to parachute school in Fort Benning, Georgia, and served in the 3rd Platoon of D Company, 82nd airborne. Stationed in the Ardennes, in very cold and wet conditions, he was evacuated after three weeks with “trench foot,” to recuperate in an American hospital in northern England. He completed his service at the end of the war as a private first class. Although he had always felt ill-equipped and inadequately trained to fight in the war, he talked with me about how combat focuses the mind, strengthens lasting attitudes, and taught him what effective leadership can accomplish.

Having returned, he completed his studies at Williams and then at Albany Medical College. In 1946/7, a six-month pathology study at Hartford’s St. Francis Hospital preceded surgical training in the Columbia division of Bellevue Hospital, New York. Leaning more toward pathology, my father went to work under Harry Zimmerman at Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx, where he published his first paper, on adult Niemann-Pick disease.

In 1952 he married Patricia Blech, a poet, scholar and translator of medieval French literature. Francophiles both, they went to live in France. Working as an unpaid postdoctoral fellow in Villejuif, France, dad was able to train with the anatomist Francoise Haguenau on a primitive RCA electron microscope. This inspired him to persuade Zimmerman at Montefiore of the promise of electron microscopy.

After the last two years of his residency in neuropathology, largely under Martin Netsky, my father took over day-to-day responsibilities at Montefiore until 1959, when he transferred to Einstein College of Medicine to head a new Division of Neuropathology. During this year he formed a mutual research program with Saul Korey, working now with a vastly superior Siemens EM. They chose Tay-Sachs and Alzheimer’s disease for investigation. For several years his team at Einstein had the field to themselves; in 1969 dad became the chair of pathology. The year 1984 presented an enticing offer to join Bob Katzman at the University of California, San Diego, as a full-time investigator.

In 1989, my father received the Distinguished Service Award from the American Association of Neuropathologists, and was a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. From 1990 to 1996 he served on the Advisory Board of the Max Planck Institute in Martinsreid, Germany. He trained more than 50 graduate fellows in experimental and diagnostic neuropathology.

My dad was very devoted to my wonderful mother, Patricia, who passed away on September 17, 2011, after 59 years of marriage. He also loved their wide variety of dogs. It was an honor, and great stroke of luck, to be his only child. I miss him very much.

University of Southampton School of Medicine

I first met Bob Terry at an International Society of Neuropathology Congress in Zürich in 1965, when we argued over lunch about the molecular structure of the multilamellar bodies in Tay-Sachs disease. Following these conversations I worked with Bob in 1967-1968 at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine on an NIH Fellowship. Bob had assembled a fantastic team that is shown in one of the photographs in the main section of this article. Cedric Raine and Peter Spencer joined the team later that year. Bob liked a good argument and he encouraged discussion from everyone.

My lasting memories are that Bob was very kind and generous to his residents and fellows; he was totally honest and straightforward. Robert Terry taught me many of the principles upon which I built my clinical and research career in neuropathology. It was with great sadness that I heard that Bob had died, but I remember the substantial contributions he made personally to neuropathology and to the training of many of his successors.

RIKEN Center for Brain Science

Bob Terry is well-known in Japan, partly because Yasuo Ihara often talks about him. I started working on neuropathology and neurochemistry of Alzheimer's disease under Yasuo's mentorship around 1994, when Bob retired. I take this coincidence as inspiration, and will continue to clarify the mechanism(s) by which protein aggregates cause neurodegenerative diseases, including AD. Bob will be remembered for a long time as a pioneer of Alzheimer's research in Japan, as well.

Boston University School of Medicine

I had the pleasure of working with Bob while he was at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, while I was in an M.D./Ph.D .program there. I will always remember the mixture of fear and admiration I felt whenever Bob asked me to join him for a brain-cutting session. Every time, he would display tremendous knowledge of neuroanatomy and appreciation of Alzheimer's pathology. However, he would also look at me with those piercing eyes of his, and ask pointed questions about Alzheimer's or neuroanatomy.

He had a razor-sharp, logical mind, and any bit of straying from facts or logical consistency provoked a concise but apt correction on his part. These were always such incredible learning experiences! Bob was a great guy.

Co-Director, Brigham and Women's Hospital's Ann Romney Center for Neurologic Diseases

What a privilege and a pleasure to have known and conversed with Bob Terry over so many years. I met Bob at a seminal NIA conference on dementia in Bethesda in 1978. That was followed by many wonderful discussions of all things Alzheimer over the last four decades.

Bob was skeptical about the primacy of amyloid in AD pathogenesis, and he was never shy about tweaking fuzzy thinking, including mine, on this contentious topic. But he was always a true gentleman—deeply courteous and friendly—a warm, caring individual to peers and students alike. He alone received the first Potamkin Award, in 1987, as a visionary "tauist" … and with good scientific balance, two unrepentant "baptists," George Glenner and I, shared it the next year.

Like so many others in our field, I was constantly inspired by Bob to think more critically, explore more carefully, and mentor more effectively. We have lost a true father figure of Alzheimerology and a great friend.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.