Can Heparin Delay Alzheimer’s Disease?

Quick Links

A drug that has been used for nearly a century to prevent and dissolve blood clots may also delay the onset of Alzheimer’s disease, according to a study in the October 8 Molecular Psychiatry. Heparin may never be prescribed for AD, but the findings reinforce the idea that similar chemicals found naturally in the brain play key roles in the disease.

- In two independent hospital systems, past heparin use was associated with a one-year delay in AD onset.

- It may block ApoE and tau from binding to endogenous heparin-like molecules.

The body’s own heparin-like molecules include heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs), which serve a wide range of functions in cell membranes and the extracellular matrix. HSPGs bind two proteins implicated in AD: ApoE and tau (Holmes et al., 2013; Rauch et al., 2018). Tau forms the neurofibrillary tangles found in AD brains, while ApoE has been implicated in both tangle and amyloid plaque pathology. ApoE4, the most important genetic determinant of late-onset AD risk, binds more tightly to HSPGs than do other ApoE forms (Arboleda-Velasquez et al., 2019).

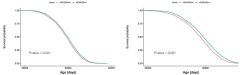

For the new study, scientists led by Benjamin Readhead of Arizona State University, Tempe, and Eric Reiman, Banner Alzheimer’s Institute, Phoenix, speculated that heparin might protect people from AD by competing with HSPGs for binding sites on ApoE or tau. To test this, they examined electronic health records of people diagnosed with AD at two large hospital systems in New York City—Mount Sinai Medical Center and Columbia University Medical Center. Even though the two systems had different patient populations, both datasets showed that people who received heparin were diagnosed with AD when they were approximately one year older than people who never received heparin.

Alzheimer’s Delayed? Survival curves show that in the MSHS (left) and CUMC hospital systems (right), people who had been given heparin (blue line) were diagnosed with AD later than those who were never given heparin (red line). [Courtesy of Readhead et al., 2024.]

“We were interested to see that the apparent protective effect of heparin was actually pretty similar across these different medical contexts,” said Readhead.

Marc Diamond of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, who was not involved in the study, echoed the sentiment. “It is important that a small, if statistically significant, effect was observed in two independent cohorts,” he wrote to Alzforum. But he pointed out that people are typically treated with heparin for only a few weeks, and that the amount that crosses into the brain is likely low. For these reasons, he thinks the findings may reflect something other than heparin treatment.

People who receive heparin have conditions that need anticoagulants, such as atrial fibrillation and heart disease, and they often have related comorbidities such as Type 2 diabetes mellitus and cerebrovascular disease. Many of the conditions associated with heparin use are themselves risk factors for AD and are treated with other drugs as well.

But while those comorbidities make it difficult to disentangle the role of heparin, any bias they introduce would be expected to weaken the results, not strengthen them, said Readhead. Indeed, when the scientists statistically controlled for comorbidities, the heparin appeared even more protective, with hazard ratios dropping from 0.89 to 0.69 in the MSSM system and from 0.80 to 0.69 in CUMC.

Readhead hopes that the findings could pave the way for new AD drugs with mechanisms similar to heparin. Moreover, he said, the study highlights the value of analyzing large datasets from electronic health records in a targeted way, with specific hypotheses guided by laboratory research.

“Electronic health records in isolation have all sorts of weaknesses. But the strength of this particular story is that it was very biologically informed by these preceding genetic and then experimental studies,” said Readhead. “If our story leaves me with a lesson, it is the power of combining these different investigational approaches.”—Nala Rogers

Nala Rogers is a freelance writer in Silver Spring, Maryland.

References

Paper Citations

- Holmes BB, DeVos SL, Kfoury N, Li M, Jacks R, Yanamandra K, Ouidja MO, Brodsky FM, Marasa J, Bagchi DP, Kotzbauer PT, Miller TM, Papy-Garcia D, Diamond MI. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans mediate internalization and propagation of specific proteopathic seeds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Aug 13;110(33):E3138-47. Epub 2013 Jul 29 PubMed.

- Rauch JN, Chen JJ, Sorum AW, Miller GM, Sharf T, See SK, Hsieh-Wilson LC, Kampmann M, Kosik KS. Tau Internalization is Regulated by 6-O Sulfation on Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans (HSPGs). Sci Rep. 2018 Apr 23;8(1):6382. PubMed.

- Arboleda-Velasquez JF, Lopera F, O'Hare M, Delgado-Tirado S, Marino C, Chmielewska N, Saez-Torres KL, Amarnani D, Schultz AP, Sperling RA, Leyton-Cifuentes D, Chen K, Baena A, Aguillon D, Rios-Romenets S, Giraldo M, Guzmán-Vélez E, Norton DJ, Pardilla-Delgado E, Artola A, Sanchez JS, Acosta-Uribe J, Lalli M, Kosik KS, Huentelman MJ, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Reiman RA, Luo J, Chen Y, Thiyyagura P, Su Y, Jun GR, Naymik M, Gai X, Bootwalla M, Ji J, Shen L, Miller JB, Kim LA, Tariot PN, Johnson KA, Reiman EM, Quiroz YT. Resistance to autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease in an APOE3 Christchurch homozygote: a case report. Nat Med. 2019 Nov;25(11):1680-1683. Epub 2019 Nov 4 PubMed.

Further Reading

Primary Papers

- Readhead B, Klang E, Gisladottir U, Vandromme M, Li L, Quiroz YT, Arboleda-Velasquez JF, Dudley JT, Tatonetti NP, Glicksberg BS, Reiman EM. Heparin treatment is associated with a delayed diagnosis of Alzheimer's dementia in electronic health records from two large United States health systems. Mol Psychiatry. 2024 Oct 8; PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

University of Texas, Southwestern Medical Center

These results are indeed fascinating. It is important that a small, if statistically significant, effect was observed in two independent cohorts. We determined that heparin (and a heparin mimetic) blocks tau binding to cell-surface HSPG, thereby preventing uptake and seeding (Holmes et al., 2013; Stopschinski et al., 2018, 2020). This implication of HSPG in pathological tau propagation was complemented by studies indicating that ApoE carrying the protective Christchurch mutation appears to bind HSPG with lower affinity than normal. The question is whether the brief exposure to heparin catalogued in the study cohorts could possibly account for a difference in AD onset.

My sense is that the odds are low for two reasons and I think other explanations should be considered. First, heparin exposure is generally fairly brief, typically a matter of weeks around surgery or treatment for a blood clot, e.g., deep vein thrombosis, or cardiovascular problems. The study doesn’t say how long people were exposed, or whether those who had longer exposure had a greater benefit. It also doesn’t specify whether individuals were treated with low molecular weight or more traditional forms of heparin, which could have different effects on tau or ApoE. Perhaps future studies could do this. Second, the amount of heparin that extravasates from the intravascular space, where it is used for anticoagulation, to the brain parenchyma, where it would potentially block ApoE or tau interactions with neurons and glia, is likely very low, as heparin is relatively large and negatively charged, and would not be expected to cross the blood brain barrier to a significant extent.

References:

Holmes BB, DeVos SL, Kfoury N, Li M, Jacks R, Yanamandra K, Ouidja MO, Brodsky FM, Marasa J, Bagchi DP, Kotzbauer PT, Miller TM, Papy-Garcia D, Diamond MI. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans mediate internalization and propagation of specific proteopathic seeds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Aug 13;110(33):E3138-47. Epub 2013 Jul 29 PubMed.

Stopschinski BE, Holmes BB, Miller GM, Manon VA, Vaquer-Alicea J, Prueitt WL, Hsieh-Wilson LC, Diamond MI. Specific glycosaminoglycan chain length and sulfation patterns are required for cell uptake of tau versus α-synuclein and β-amyloid aggregates. J Biol Chem. 2018 Jul 6;293(27):10826-10840. Epub 2018 May 11 PubMed.

Stopschinski BE, Thomas TL, Nadji S, Darvish E, Fan L, Holmes BB, Modi AR, Finnell JG, Kashmer OM, Estill-Terpack S, Mirbaha H, Luu HS, Diamond MI. A synthetic heparinoid blocks Tau aggregate cell uptake and amplification. J Biol Chem. 2020 Mar 6;295(10):2974-2983. Epub 2020 Jan 23 PubMed.

Universities of Manchester and Oxford

It is surprising that no mention was made that not only APOE and tau, but also HSV1, along with diverse types of infectious pathogen—viruses, including SARS-COV-2, bacteria, and parasites—use HSPG for the first stage of attachment and entry into cells (Akhtar and Shukla, 2009), and that heparin inhibits this binding and stops their cellular internalization. The possible use of heparin and heparan sulphate as antiviral agents, though, has been restricted because of their anticoagulant effects. Nonetheless, because treatment with the conventional anti-herpes antivirals, acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir (which act quite differently, by stopping viral DNA replication) reduces substantially the risk of AD as shown in a number of studies, treatment with heparin-binding peptides as alternative or additional antivirals might be worth considering, as they are non-anticoagulant agents capable of antagonizing the binding of heparin-binding pathogens to HSPGs (and might allow their usage also in COVID-19 infection (Tavassoly et al. 2020).

References:

Akhtar J, Shukla D. Viral entry mechanisms: cellular and viral mediators of herpes simplex virus entry. FEBS J. 2009 Dec;276(24):7228-36. PubMed.

Tavassoly O, Safavi F, Tavassoly I. Heparin-binding Peptides as Novel Therapies to Stop SARS-CoV-2 Cellular Entry and Infection. Mol Pharmacol. 2020 Nov;98(5):612-619. Epub 2020 Sep 10 PubMed.

University of Toronto

Heparin and heparan sulfate and are chemically related αβ-linked glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) composed of alternating sequences of glucosamine and uronic acid; the amino sugars may be N-acetylated or N-sulfated, with the latter being unique to these two polysaccharides. Extracellular complex polysaccharides, belonging to the family of heparin/heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans (HS-GAG), play important roles in multiple biological processes at the cell–tissue–organ interface involving anticoagulation, microbial (viral) invasion, cell growth, and angiogenesis. Within the context of Alzheimer’s disease, HS-GAGs directly bind and accelerate Aβ aggregation, mediate Aβ internalization and cytotoxicity, and co-deposit with Aβ in plaques; HS-GAG also regulates Aβ clearance and neuroinflammation in vivo (Petersen et al., 2024; Ozsan McMillan et al., 2023). Similarly, HS-GAGs directly bind to tau, co-deposit with tau in AD brain, and modulate tau secretion, internalization, and aggregation (Zhu et al., 2022).

The notion that heparin or heparan sulfate (or other sulfated glycosaminoglycans; e.g., chondroitin sulfate) could be the starting point in the development of AD therapeutics is a concept we have studied extensively. Based on some preliminary molecular modelling calculations (Rozas and Weaver, 1996), we synthesized and studied more that 1,000 small molecule sulfate/sulfonate analogues as HS-GAG mimics in an attempt to identify a compound to reproduce the potential therapeutic effectiveness of GAGs such as heparin (Kisilevsky et al., Method for treating amyloidosis, Application No. 08/542,997; filed October 13, 1995. U.S. Patent No. 5,840,294, issued November 24, 1998; Kisilevsky et al., A method of treating amyloidosis. Application No. 08/472,692; filed June 6, 1995. U.S. Patent No. 5,728,375, issued March 17, 1998; Kisilevsky et al., A method of treating amyloidosis. Application No. 08/403,230; filed March 15, 1995. U.S. Patent 5,643,562, issued July 01, 1997). We conjectured that HS-GAG binds electrostatically to the HHQK domain within Aβ with the anionic sulfates of HS-GAG interacting with the cationic H and K residues. However, such highly polar small molecules cannot cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Accordingly, we extended our target site on Aβ to -EVHHQK to enable including the glutamate (E) residue in the hopes that we could design a zwitterionic compound capable of traversing the BBB by active transport. Eventually, homotaurine was selected as a putative candidate and completed Phase 3 human trials as tramiprosate (Alzhemed). Although this clinical trial for AD failed, the concept of therapeutics based on HS-GAG (i.e. GAG-mimetics) persists as an interesting possibility.

References:

Ozsan McMillan I, Li JP, Wang L. Heparan sulfate proteoglycan in Alzheimer's disease: aberrant expression and functions in molecular pathways related to amyloid-β metabolism. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2023 Apr 1;324(4):C893-C909. Epub 2023 Mar 6 PubMed.

Petersen SI, Okolicsanyi RK, Haupt LM. Exploring Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans as Mediators of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell Neurogenesis. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2024 Mar 28;44(1):30. PubMed.

Zhu Y, Gandy L, Zhang F, Liu J, Wang C, Blair LJ, Linhardt RJ, Wang L. Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans in Tauopathy. Biomolecules. 2022 Nov 30;12(12) PubMed.

Rozas I, Weaver DF. Ab initio study of the methylsulfonate and phenylsulfonate anions. DOI https://doi.org/10.1039/P29960000461

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.