Could Bigger, More Complex Brains Explain Decreasing Dementia Incidence?

Quick Links

Over the past three decades, the incidence of dementia has been declining in the U.S. and Europe. One reason might be that people’s brains have been getting bigger, say scientists led by Charles DeCarli at the University of California, Davis, and Sudha Seshadri of the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio. In the March 25 JAMA Neurology, they reported that people born in the 1970s had 15 percent more surface area in their cortices than people born in the 1930s. This could increase their cognitive reserve, beefing up their buffer against cognitive decline later in life, the authors concluded.

- In some countries, dementia incidence has been falling.

- Now, scientists say better brain development might explain the trend.

- People born in the 1970s have more cortical surface area and brain volume than people born in the ’30s.

“The findings [are] fascinating and suggest that changing exposures in early life might specifically influence brain development,” wrote Jonathan Schott, University College London. “Whether these changes are contributing to the decreased incidence of dementia seen in Western countries is, at this stage, less clear” (comment below).

Prashanthi Vemuri of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, shared these sentiments. “Do these secular trends in the improvement of brain health underlie the decrease in dementia risk? The jury may be still out, but the authors are commended for investigating new avenues,” she wrote in an editorial.

In the U.S. and Europe, dementia incidence has fallen about 25 percent since the 1990s (Feb 2023 news; Jul 2013 conference news). Scientists debate the reasons—from better diet, exercise, and education to improved cardiovascular health. Seshadri and colleagues had posited that that latter contributed to falling dementia rates in the Framingham Heart Study (Feb 2016 news).

DeCarli suspected that improved brain development might be another factor. To find out, he analyzed structural MRI scans from a subset of 3,226 Framingham participants, half of whom were women, who were born from 1925 to 1968. On average, participants were 58 when they got their MRI scans. DeCarli measured the total intracranial volume, the size of the hippocampus, and the thickness and surface area of the cortical white and gray matter. All values were adjusted for age, sex, and height, all of which are known to affect head size and/or brain volume.

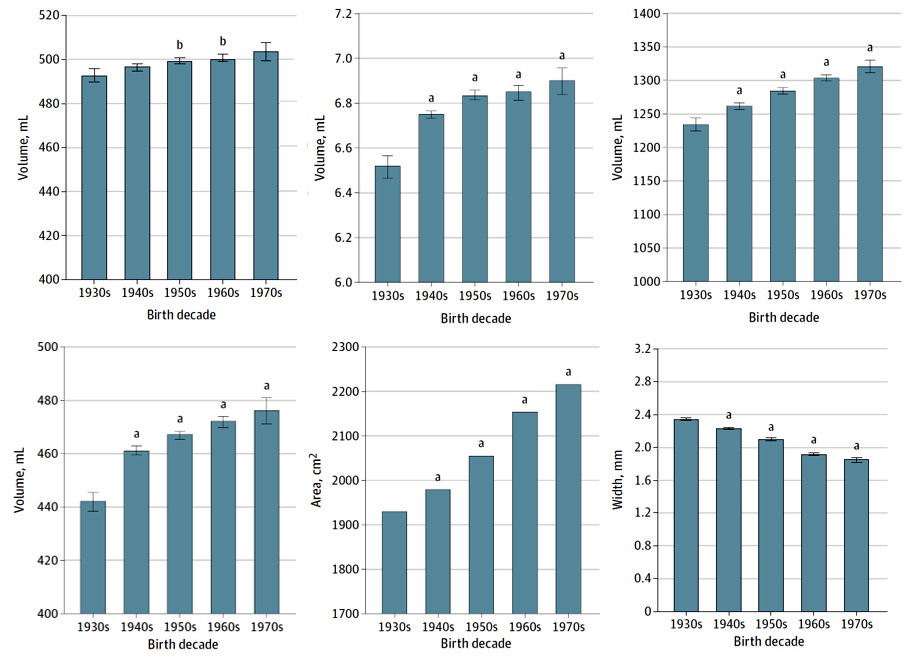

Participants born more recently had larger brains, as measured by all those parameters but cortical thickness. Compared to people born between 1925 and 1935, those born from 1965 to 1975 had 2.2 percent more cortical gray matter, 5.7 percent larger hippocampi, 6.6 percent more intracranial volume, and 7.7 percent more cerebral white matter. They also had a whopping 14.9 percent larger cortical surface area (image below). DeCarli thinks that deeper gyri and sulci, i.e., the cortical ridges and valleys, account for the surface area and white matter improvement, both of which would enable more neuron connections.

That theory needs to be tested, particularly since cortical thickness bucked the trend, clocking in at 21 percent thinner. The authors noted that deeper gyri in the absence of additional gray matter would thin the cortical parenchyma (reviewed by White et al., 2010). While this might seem harmful, DeCarli believes that, when the gyri deepen, the neurons there make more extensive connections, though this has yet to be empirically tested.

Bigger Brains? People born in later decades had more cortical gray matter (top left), larger hippocampi (top middle), a bigger intracranial volume (top right), more cerebral white matter (bottom left), and more cortical surface area (bottom middle). However, their cortices thinned (bottom right). [Courtesy of DeCarli et al., JAMA Neurology, 2024.]

What would cause brain size to increase? DeCarli attributes it to environmental factors. Specifically, better pre- and postnatal health, balanced nutrition, and access to good early education.

As for the implications of a larger brain with more neuronal connections, the researchers hark back to the falling dementia rates over the past 40 years. They believe more cognitive reserve protected against dementia, partly explaining this decline (Aug 2017 conference news; reviewed by van Loenhoud et al., 2018). Schott was intrigued that increased brain volume over the years might improve cognitive reserve or resilience to AD, but not convinced. “Given the relatively young age, 45 to 74 years, further follow-up to capture cognitive outcomes and dementia diagnosis rates is required to address these ideas,” he wrote.

Because brain size decreases with age, DeCarli is analyzing longitudinal structural MRI to see if bigger brains shrink more slowly than smaller ones, which would help explain the falling dementia rates.—Chelsea Weidman Burke

References

News Citations

- Those Declining Dementia Rates? It's Not the Plaques and Tangles

- Dementia Prevalence Falls in England

- Falling Dementia Rates in U.S. and Europe Sharpen Focus on Lifestyle

- Teasing Out the Brain Features Behind Cognitive Reserve

Paper Citations

- White T, Su S, Schmidt M, Kao CY, Sapiro G. The development of gyrification in childhood and adolescence. Brain Cogn. 2010 Feb;72(1):36-45. Epub 2009 Nov 25 PubMed.

- van Loenhoud AC, Groot C, Vogel JW, van der Flier WM, Ossenkoppele R. Is intracranial volume a suitable proxy for brain reserve?. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018 Sep 11;10(1):91. PubMed.

Further Reading

No Available Further Reading

Primary Papers

- DeCarli C, Maillard P, Pase MP, Beiser AS, Kojis D, Satizabal CL, Himali JJ, Aparicio HJ, Fletcher E, Seshadri S. Trends in Intracranial and Cerebral Volumes of Framingham Heart Study Participants Born 1930 to 1970. JAMA Neurol. 2024 May 1;81(5):471-480. PubMed.

- Vemuri P. Improving Trends in Brain Health Explain Declining Dementia Risk?. JAMA Neurol. 2024 May 1;81(5):442-443. PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

University College London

The findings of height-, age-, and sex-independent increases in intracranial, hippocampal, and white-matter volumes and in cortical surface area in members of the Framingham Heart Study born over successive decades are fascinating and suggest that changing exposures in early life might specifically influence brain development. Whether these changes contribute to the decreased incidence of dementia seen in Western countries is, at this stage, less clear. Pathological studies in other cohorts have shown significant reductions in cerebrovascular pathology over the years, likely related to improved management of vascular risk factors in prior decades, which would seem likely to be a major influence on changing dementia rates (Grodstein et al., 2023). It is of course possible that increased brain volumes over the decades might improve reserve/resilience to AD and neurodegenerative pathologies—which, in contrast to cerebrovascular disease, do not seem to be changing over time (Grodstein et al., 2023).

Given the relatively young age of this cohort, 45 to 74 years, further follow-up to capture cognitive outcomes and dementia diagnosis rates, ideally with autopsy confirmation of diagnosis, is required to address this idea. More broadly, studies such as this demonstrate the power of combining cohorts studied prospectively over many years with brain imaging and other biomarkers of brain health to determine potentially modifiable early life risk/protective factors for cognition and dementia in later life.

References:

Grodstein F, Leurgans SE, Capuano AW, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Trends in Postmortem Neurodegenerative and Cerebrovascular Neuropathologies Over 25 Years. JAMA Neurol. 2023 Apr 1;80(4):370-376. PubMed.

University of South Florida

DeCarli et al. provide evidence for secular trends in intracranial volume, white- and gray-matter volume, hippocampal volume, and cortical surface area for birth cohorts from 1930 to 1970. Although ICV is established fairly early in life and does not change over the remainder of the lifespan, other volumes, including hippocampal volume, decrease with age. The authors of this report address this issue by adjusting for age at the MRI scan as well as comparing two groups of participants from adjacent birth cohorts of similar mean age. They note that the increases in brain volume parallel earlier findings of declining incidence of dementia over time in the Framingham Study.

Although the observations of decreased dementia incidence and increased brain size over time are important, data from studies measuring the association of head size with dementia in individuals provide additional support for this relationship. Beginning with Schofield et al. (1995), numerous studies have shown associations between measures of larger brain size and lower risk of dementia in individual participants (Borenstein and Mortimer, 2016).

In 2001, in a prospective study we showed that among individuals who carried one APOE4 allele, those with smaller head circumferences had a 12-fold higher risk of incident probable AD compared to those with larger head circumferences (Borenstein Graves et al., 2001). A later analysis from the Nun Study (Mortimer et al., 2003) demonstrated that among nuns with less than a college education, smaller head circumference was associated with a higher prevalence of dementia. In 2009, this finding in the Nun Study was extended to incident dementia, with both smaller head circumference and lower education increasing the risk of dementia independent of the severity of AD neuropathology at autopsy (Mortimer et al. 2009). Finally in a large prospective community study in China, we reported that smaller head circumference combined with lower education predicted a higher risk of incident dementia (Wang et al., 2019).

Among other factors, the presence of small strokes greatly increases the risk of dementia (Snowdon et al., 1996). It is likely that all three factors (brain size, education, and cerebrovascular disease) play a role in mitigating the effects of AD pathology on the expression of dementia. Therefore, it might be expected that secular effects in all three variables would result in declines in dementia and AD incidence over time.

References:

Schofield PW, Mosesson RE, Stern Y, Mayeux R. The age at onset of Alzheimer's disease and an intracranial area measurement. A relationship. Arch Neurol. 1995 Jan;52(1):95-8. PubMed.

Borenstein AR, Mortimer JA. Alzheimer’s Disease, from Life Course Perspectives on Risk Reduction. Elsevier: London, 2016.

Borenstein Graves A, Mortimer JA, Bowen JD, McCormick WC, McCurry SM, Schellenberg GD, Larson EB. Head circumference and incident Alzheimer's disease: modification by apolipoprotein E. Neurology. 2001 Oct 23;57(8):1453-60. PubMed.

Mortimer JA, Snowdon DA, Markesbery WR. Head circumference, education and risk of dementia: findings from the Nun Study. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2003 Aug;25(5):671-9. PubMed.

Mortimer JA, Snowdon DA, Markesbery, WR. Larger head circumference and greater education provide protection against incident dementia independent of the severity of Alzheimer pathology: The Nun Study. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2009; 5:379.

Wang F, Mortimer JA, Ding D, Luo J, Zhao Q, Liang X, Wu W, Zheng L, Guo Q, Borenstein AR, Hong Z. Smaller Head Circumference Combined with Lower Education Predicts High Risk of Incident Dementia: The Shanghai Aging Study. Neuroepidemiology. 2019;53(3-4):152-161. Epub 2019 Jul 15 PubMed.

Snowdon DA, Greiner LH, Mortimer JA, Riley KP, Greiner PA, Markesbery WR. Brain infarction and the clinical expression of Alzheimer disease. The Nun Study. JAMA. 1997 Mar 12;277(10):813-7. PubMed.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.