Pocketful of Posies: Does a Supersized Vesicle Bouquet Promote ALS?

Quick Links

A bouquet of protein strands, capped with presynaptic vesicles, offers up a clue to neurotransmission defects that might occur early in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. This is the essence of a paper in the July 10 Cell Reports by senior author Patrik Verstreken and colleagues at the VIB Center for the Biology of Disease in Leuven, Belgium. The “flowers” in the bunch undergo acetylation and deacetylation by elongator protein 3 (ELP3) and histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6), respectively. TDP-43 also takes part in the arrangement because it regulates HDAC6 expression. Variants of both TDP-43 and ELP3 increase a person’s risk of developing ALS.

The protein subject to acetyl modification is called Bruchpilot. Fruit flies with Bruchpilot mutations are poor aerialists—hence the name, which is German for “crash pilot” (Wagh et al., 2006). The protein forms long strands that organize into a configuration called a T-bar (see image below). The amino termini cluster together at the synaptic membrane and the carboxyl ends splay out above, where they gather vesicles (Fouquet et al., 2009). Verstreken’s lab previously showed that ELP3 mutant fly neurons poorly acetylate Bruchpilot, causing the formation of widened T-bars that collect extra vesicles and transmit neural signals faster than normal (Miskiewicz et al., 2011). Verstreken suspects that the positively charged lysines in Bruchpilot’s carboxyl terminus repel each other, allowing the stems in the bouquet to spread out and collect more vesicles. Acetylation by ELP3 quenches the positive charge, and the Bruchpilot stems cluster more tightly into smaller T-bars with fewer vesicles. Verstreken has yet to confirm this model.

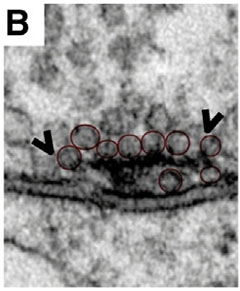

Bruchpilot strands form a T-bar at the presynaptic membrane, where they tether vesicles awaiting release. When HDAC6 is overexpressed, as shown, the T-bars expand and accommodate more vesicles than normal. [Courtesy of Cell Reports, Miskiewicz et al., Figure 1.]

If ELP3 acetylates Bruchpilot, then the cell likely also contains a deacetylase, reasoned first authors Katarzyna Miskiewicz and Liya Jose. A prime suspect was HDAC6, because it functions in the cytosol unlike most deacetylases, it is upregulated by TDP-43, and its expression is altered in ALS-model flies, Verstreken said (Kim et al., 2010; Fiesel et al., 2010). Unlike most deacetylases, HDAC6 acts in the cytosol. The scientists found that it directly deacetylates Bruchpilot in vitro. They also determined that flies overexpressing HDAC6 poorly acetylated Bruchpilot in the brain, whereas flies lacking the enzyme made an abundance of modified Bruchpilot.

When the authors examined the fly larvae’s neuromuscular junctions with electron microscopy, they observed that flies without HDAC6 had puny T-bars with but a few vesicles hanging on. In flies with excess HDAC6, the T-bars were broad, with more attached vesicles.

Do those extra vesicles change how the synapse functions? Performing electrophysiology on larval neuromuscular junctions, Miskiewicz and colleagues showed that the amplitude of current transmitted was higher in HDAC6 overexpressers and lower in HDAC6-null mutants than in control samples.

Because HDAC6 depends on TDP-43 for proper expression, the scientists studied Bruchpilot in flies overexpressing human TDP-43, and in flies lacking the Drosophila homolog of TDP-43, TBPH. As expected, TDP-43 upregulated HDAC6, T-bar size, vesicle recruitment, and neural signaling. TDP-43 mutations associated with ALS led to the largest T-bars.

If the problem in TDP-43 mutant flies is under-acetylation of Bruchpilot, then extra ELP3 or less HDAC6 should help, the authors reasoned. Indeed, when they combined TDP-43 mutations with those genotypes, the T-bars and associated synaptic activity returned to normal. In addition, it fixed the movement disability of TDP-43 mutant flies.

“Acetylation defects could be a pathologic cascade that leads to synaptic defects early on in ALS,” Verstreken surmised. The excess neurotransmission could lead to excitotoxicity plus the muscle twitches and paralysis typical of the disease, he speculated. However, Verstreken cautioned, “This is only in fruit flies”; with respect to humans, “there is a little problem.” While Bruchpilot is conserved across species, the human version lacks the carboxyl terminus, where the fly protein collects acetyl groups. Verstreken suspects that in people, a different protein tethers synaptic vesicles and undergoes acetylation. He has several suspects in mind, including UNC13A, an ALS gene whose protein manages neurotransmitter release (Diekstra et al., 2012). Verstreken plans to examine T-bars and their acetylation status in human muscle biopsy or autopsy brain-stem tissue.

“It is possible that the same pathways are relevant in humans,” agreed Ammar Al-Chalabi of King’s College London in an email to Alzforum. “If so … then a therapeutic approach to consider would be to increase ELP3 expression.” Alternatively, Verstreken suggested, HDAC6 inhibitors might be beneficial. Supporting his idea, researchers recently showed that deleting HDAC6 extended survival in ALS model mice (Taes et al., 2013).—Amber Dance

References

Paper Citations

- Wagh DA, Rasse TM, Asan E, Hofbauer A, Schwenkert I, Dürrbeck H, Buchner S, Dabauvalle MC, Schmidt M, Qin G, Wichmann C, Kittel R, Sigrist SJ, Buchner E. Bruchpilot, a protein with homology to ELKS/CAST, is required for structural integrity and function of synaptic active zones in Drosophila. Neuron. 2006 Mar 16;49(6):833-44. PubMed.

- Fouquet W, Owald D, Wichmann C, Mertel S, Depner H, Dyba M, Hallermann S, Kittel RJ, Eimer S, Sigrist SJ. Maturation of active zone assembly by Drosophila Bruchpilot. J Cell Biol. 2009 Jul 13;186(1):129-45. PubMed.

- Miśkiewicz K, Jose LE, Bento-Abreu A, Fislage M, Taes I, Kasprowicz J, Swerts J, Sigrist S, Versées W, Robberecht W, Verstreken P. ELP3 controls active zone morphology by acetylating the ELKS family member Bruchpilot. Neuron. 2011 Dec 8;72(5):776-88. PubMed.

- Kim SH, Shanware NP, Bowler MJ, Tibbetts RS. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated proteins TDP-43 and FUS/TLS function in a common biochemical complex to co-regulate HDAC6 mRNA. J Biol Chem. 2010 Oct 29;285(44):34097-105. PubMed.

- Fiesel FC, Voigt A, Weber SS, Van den Haute C, Waldenmaier A, Görner K, Walter M, Anderson ML, Kern JV, Rasse TM, Schmidt T, Springer W, Kirchner R, Bonin M, Neumann M, Baekelandt V, Alunni-Fabbroni M, Schulz JB, Kahle PJ. Knockdown of transactive response DNA-binding protein (TDP-43) downregulates histone deacetylase 6. EMBO J. 2010 Jan 6;29(1):209-21. Epub 2009 Nov 12 PubMed.

- Diekstra FP, van Vught PW, van Rheenen W, Koppers M, Pasterkamp RJ, van Es MA, Schelhaas HJ, de Visser M, Robberecht W, Van Damme P, Andersen PM, van den Berg LH, Veldink JH. UNC13A is a modifier of survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol Aging. 2012 Mar;33(3):630.e3-8. Epub 2011 Nov 25 PubMed.

- Taes I, Timmers M, Hersmus N, Bento-Abreu A, Van Den Bosch L, Van Damme P, Auwerx J, Robberecht W. Hdac6 deletion delays disease progression in the SOD1G93A mouse model of ALS. Hum Mol Genet. 2013 May 1;22(9):1783-90. Epub 2013 Jan 30 PubMed.

External Citations

Further Reading

Papers

- Simpson CL, Lemmens R, Miskiewicz K, Broom WJ, Hansen VK, van Vught PW, Landers JE, Sapp P, Van Den Bosch L, Knight J, Neale BM, Turner MR, Veldink JH, Ophoff RA, Tripathi VB, Beleza A, Shah MN, Proitsi P, Van Hoecke A, Carmeliet P, Horvitz HR, Leigh PN, Shaw CE, van den Berg LH, Sham PC, Powell JF, Verstreken P, Brown RH, Robberecht W, Al-Chalabi A. Variants of the elongator protein 3 (ELP3) gene are associated with motor neuron degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2009 Feb 1;18(3):472-81. PubMed.

- Shahidullah M, Le Marchand SJ, Fei H, Zhang J, Pandey UB, Dalva MB, Pasinelli P, Levitan IB. Defects in synapse structure and function precede motor neuron degeneration in Drosophila models of FUS-related ALS. J Neurosci. 2013 Dec 11;33(50):19590-8. PubMed.

- Kittel RJ, Wichmann C, Rasse TM, Fouquet W, Schmidt M, Schmid A, Wagh DA, Pawlu C, Kellner RR, Willig KI, Hell SW, Buchner E, Heckmann M, Sigrist SJ. Bruchpilot promotes active zone assembly, Ca2+ channel clustering, and vesicle release. Science. 2006 May 19;312(5776):1051-4. PubMed.

- Singh N, Lorbeck MT, Zervos A, Zimmerman J, Elefant F. The histone acetyltransferase Elp3 plays in active role in the control of synaptic bouton expansion and sleep in Drosophila. J Neurochem. 2010 Oct;115(2):493-504. PubMed.

Primary Papers

- Miskiewicz K, Jose LE, Yeshaw WM, Valadas JS, Swerts J, Munck S, Feiguin F, Dermaut B, Verstreken P. HDAC6 is a Bruchpilot deacetylase that facilitates neurotransmitter release. Cell Rep. 2014 Jul 10;8(1):94-102. Epub 2014 Jun 26 PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

Kings College London

This is an interesting study and links two pathways in a fly model of ALS. It is possible that the same pathways are relevant in humans, since there is an association of ELP3 alleles with ELP3 expression and ALS disease status in humans, and the changes are in a consistent direction with what has been observed in this study. The Bruchpilot equivalent in humans does not contain a long tail, so the acetylation target may be different. If similar acetylation relationships between the two pathways exist in humans, and the effects on neurotransmission and disease status also exist, then a therapeutic approach to consider would be to increase ELP3 expression.

View all comments by Ammar Al-ChalabiMake a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.