Revised Guidelines for Diagnosing Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

Quick Links

It’s not easy to diagnose the rare tauopathy progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), but things might be looking up now that the old diagnostic guidelines have received a reboot. Armed with recent research findings and autopsy-confirmed cases, scientists led by Guenter Höglinger, German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE), Munich, and Irene Litvan, University of California, San Diego, have devised a new set of guidelines that not only help diagnose the disease earlier, but account for more of its different clinical presentations. Constructed by 47 clinician-researchers in this small field, the guidelines appear in the June issue of the journal Movement Disorders.

“We hope to identify patients with more subtle clinical symptoms in a much milder clinical state, as those patients would benefit more from a disease-modifying therapy,” said Höglinger. “Hopefully we will also be able to incorporate patients with other manifestations of the disease into clinical trials.”

“Professor Höglinger and his colleagues of the MDS-PSP study group are to be congratulated on setting new criteria,” John Steele wrote to Alzforum. Steele, who at the time worked with Jerzy Olszewski and J.C. Richardson at the University of Toronto, first described the disease in the 1960s (Steele et al., 1964). Indeed, PSP used to be called Steele-Richardson-Olszewski or Richardson syndrome.

The current diagnostic guidelines for PSP appeared almost two decades ago. They require both ocular-motor and postural problems to be present for a person to be diagnosed with PSP (Litvan et al., 1996). Over the years, these criteria proved specific for people with the typical presentation of the disease. However, a person needed to be relatively advanced in their course to be diagnosed. What’s more, the guidelines fail to pick up on cases that aren’t typical. For example, an atypical patient may have underlying PSP pathology, marked by aggregates of the four-repeat splice form of the microtubule-associated protein tau, but their first symptoms may look more like frontotemporal dementia, or Parkinson’s disease.

To design new criteria that capture a broader range of disease and catch it earlier, Hoeglinger and colleagues reviewed 462 articles about PSP, published after the previous guidelines, from the PubMed, Cochrane, Medline, and PSYCInfo databases. They also examined banked brain tissue that was accompanied by antemortem clinical data from 206 patients with PSP, as well as 231 disease controls who had had other proteinopathies.

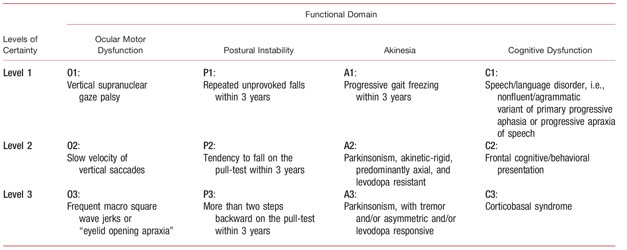

Based on these data, the scientists built a system that addressed four categories of symptoms, up from the previous two. They kept ocular-motor dysfunction and postural instability. They added akinesia, in which voluntary movement is lost or impaired, and cognitive deficits. Depending on the severity of each clinical symptom, patients were assigned a level of certainty of one through three, with one being the most indicative of PSP (see image below).

Clinical Grid: The new PSP criteria incorporate four categories of clinical features. Lower-number levels imply more diagnostic certainty. [Courtesy of Hoeglinger et al., 2017, Mov Disord.]

The authors then devised a plan for how to translate those assessments into a diagnosis. To qualify for “probable” PSP, a person had to present with an ocular-motor problem plus one other category of deficit. For instance, restricted vertical gaze coupled with apathy or slowed thinking would be deemed probable PSP with a predominant frontal presentation. “Possible” PSP requires some sort of ocular-motor deficit either on its own or together with a different set of symptoms, for example, loss of grammar or limb rigidity. The one exception to the rule of requiring symptoms from two categories is akinesia, which is usually an symptom of advanced PD. Akinesia by itself is sufficient for a PSP diagnosis, because such an advanced PD symptom occurring early in disease raises suspicion of PSP rather than PD, Hoeglinger said.

The authors also introduced a new category called “suggestive of PSP.” These patients might have an ocular motor dysfunction, or not. They do not pass the threshold for possible or probable PSP, but may develop qualifying symptoms down the line. They may only have postural problems, or be unable to open their eyelids after closing them, for instance.

Since the new system for diagnosis is complicated, the researchers are developing an app that will help neurologists. The idea is that the clinician enters the symptom levels spelled out in the table, and the app will spit back out the diagnosis and certainty level.

Why make the system complex? Each of the clinical categories is useful for a different purpose, wrote the authors. In therapeutic and biological studies, only people with probable PSP should be included, since people with other diseases can dilute the outcome signals. This applies particularly to clinical trials currently underway for anti-tau antibodies and compounds that counter tau aggregation (Apr 2017 news). Possible PSP, on the other hand, might be well-suited for epidemiologic studies and clinical care, where researchers don’t want to miss cases of true PSP. People with “suggestive” symptoms could be included in longitudinal observational studies that map the progression of PSP. They could also help with development of biomarkers that herald early disease, and stand to benefit most from future disease modifying therapies.

The next step will be to validate the new criteria, said Hoeglinger. Two studies are underway—a retrospective study that applies the criteria to an independent set of autopsy-confirmed cases, and an international prospective study in the U.S., U.K., Europe, and Japan that will follow PSP patients as their disease progresses.—Gwyneth Dickey Zakaib

References

News Citations

Paper Citations

- STEELE JC, RICHARDSON JC, OLSZEWSKI J. PROGRESSIVE SUPRANUCLEAR PALSY. A HETEROGENEOUS DEGENERATION INVOLVING THE BRAIN STEM, BASAL GANGLIA AND CEREBELLUM WITH VERTICAL GAZE AND PSEUDOBULBAR PALSY, NUCHAL DYSTONIA AND DEMENTIA. Arch Neurol. 1964 Apr;10:333-59. PubMed.

- Litvan I, Agid Y, Calne D, Campbell G, Dubois B, Duvoisin RC, Goetz CG, Golbe LI, Grafman J, Growdon JH, Hallett M, Jankovic J, Quinn NP, Tolosa E, Zee DS. Clinical research criteria for the diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy (Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome): report of the NINDS-SPSP international workshop. Neurology. 1996 Jul;47(1):1-9. PubMed.

Further Reading

Papers

- Elahi FM, Miller BL. A clinicopathological approach to the diagnosis of dementia. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017 Aug;13(8):457-476. Epub 2017 Jul 14 PubMed.

- Boxer AL, Yu JT, Golbe LI, Litvan I, Lang AE, Höglinger GU. Advances in progressive supranuclear palsy: new diagnostic criteria, biomarkers, and therapeutic approaches. Lancet Neurol. 2017 Jul;16(7):552-563. Epub 2017 Jun 13 PubMed.

- Respondek G, Kurz C, Arzberger T, Compta Y, Englund E, Ferguson LW, Gelpi E, Giese A, Irwin DJ, Meissner WG, Nilsson C, Pantelyat A, Rajput A, van Swieten JC, Troakes C, Josephs KA, Lang AE, Mollenhauer B, Müller U, Whitwell JL, Antonini A, Bhatia KP, Bordelon Y, Corvol JC, Colosimo C, Dodel R, Grossman M, Kassubek J, Krismer F, Levin J, Lorenzl S, Morris H, Nestor P, Oertel WH, Rabinovici GD, Rowe JB, van Eimeren T, Wenning GK, Boxer A, Golbe LI, Litvan I, Stamelou M, Höglinger GU, Movement Disorder Society-Endorsed PSP Study Group. Which ante mortem clinical features predict progressive supranuclear palsy pathology?. Mov Disord. 2017 Jul;32(7):995-1005. Epub 2017 May 13 PubMed.

- Whitwell JL, Höglinger GU, Antonini A, Bordelon Y, Boxer AL, Colosimo C, van Eimeren T, Golbe LI, Kassubek J, Kurz C, Litvan I, Pantelyat A, Rabinovici G, Respondek G, Rominger A, Rowe JB, Stamelou M, Josephs KA, Movement Disorder Society-endorsed PSP Study Group. Radiological biomarkers for diagnosis in PSP: Where are we and where do we need to be?. Mov Disord. 2017 Jul;32(7):955-971. Epub 2017 May 13 PubMed.

Primary Papers

- Höglinger GU, Respondek G, Stamelou M, Kurz C, Josephs KA, Lang AE, Mollenhauer B, Müller U, Nilsson C, Whitwell JL, Arzberger T, Englund E, Gelpi E, Giese A, Irwin DJ, Meissner WG, Pantelyat A, Rajput A, van Swieten JC, Troakes C, Antonini A, Bhatia KP, Bordelon Y, Compta Y, Corvol JC, Colosimo C, Dickson DW, Dodel R, Ferguson L, Grossman M, Kassubek J, Krismer F, Levin J, Lorenzl S, Morris HR, Nestor P, Oertel WH, Poewe W, Rabinovici G, Rowe JB, Schellenberg GD, Seppi K, van Eimeren T, Wenning GK, Boxer AL, Golbe LI, Litvan I, Movement Disorder Society-endorsed PSP Study Group. Clinical diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy: The movement disorder society criteria. Mov Disord. 2017 Jun;32(6):853-864. Epub 2017 May 3 PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

Professor Höglinger and his colleagues of the MDS-PSP study group are to be congratulated on setting new criteria which are both sensitive and specific, and which optimize the early clinical diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP).

During the 1950s, in Toronto, neurologist J.C. Richardson identified patients with an unfamiliar syndrome of vertical gaze and pseudobulbar palsy, nuchal dystonia, and dementia. He termed the syndrome progressive supranuclear palsy, and with the publication of our paper in 1964, this designation became the name of the disease which had occasioned the syndrome (Steele et al., 1964).

Recently the syndrome he described has become known as Richardson's syndrome. But the name of the disease, which is a 4R tauopathy, remains firmly established as PSP. Some refer to it as SRO or Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome, though I have hoped it could be known simply as Richardson's disease, to acknowledge his seminal observation.

In 1964, when describing this neurodegeneration, neuropathologist Jerzy Olszewski and I were surprised that all seven patients had exhibited the same unusual clinical syndrome despite widespread and heterogeneous neurofibrillary degeneration in subcortical nuclei, the brain stem and cerebellum.

He predicted that others with the same disease would suffer various symptoms, as different nuclei were affected, at different times and to different degrees.

Many years later, his prediction is borne out. In studies of those who meet the pathological criteria of PSP, i.e., a tauopathy which accumulates 4R tau in nerve cells, oligodendrocytic coils and astrocytic tufts, we now know that the majority begin with a symptom other than that of Richardson's syndrome.

The new MDS criteria emphasize these many phenotypic variants, which we were not previously aware of and which were not captured by NINDS/SPSP criteria developed in 1996. They will improve the diagnosis, awareness, and understanding of PSP; they will emphasize the variants of clinical presentation; and they will be helpful in research and clinical practice.

I look forward to a MDS/PSP web base to implement the criteria, and video tutorials to facilitate their application.

References:

STEELE JC, RICHARDSON JC, OLSZEWSKI J. PROGRESSIVE SUPRANUCLEAR PALSY. A HETEROGENEOUS DEGENERATION INVOLVING THE BRAIN STEM, BASAL GANGLIA AND CEREBELLUM WITH VERTICAL GAZE AND PSEUDOBULBAR PALSY, NUCHAL DYSTONIA AND DEMENTIA. Arch Neurol. 1964 Apr;10:333-59. PubMed.

Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München

For the very first time in the field of movement disorders, these criteria allow us to introduce in the clinical terminology a prediction of the underlying pathology to the molecular level.

In my opinion, the diagnostic category of "probable 4 repeat tauopathy" is in a way the logical consequence of the research in the past decade, but in another way it is also a seminal step forward. The new category of “probable 4R-tauopathies,” according to the Movement Disorder Society Criteria - Clinical Diagnosis of Progressive Supranuclear Palsy, comprise patients with possible PSP-SL (oculomotor dysfunction + nonfluent/agrammatic variant of primary progressive aphasia) or PSP-CBS (oculomotor dysfunction + corticobasal syndrome).

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.