TREM2 Variants and CSF sTREM2 Levels Differ by Race

Quick Links

Some studies have suggested that Alzheimer’s disease biomarker levels may differ by race. Now, researchers led by John Morris and Suzanne Schindler, Washington University, St. Louis, offer a genetic explanation—at least for soluble TREM2, the extracellular domain of the microglial receptor that ends up in the cerebrospinal fluid. In the March 4 Neurology Genetics, they reported that African Americans are more likely to carry TREM2 variants that dampen the protein’s expression than are non-Hispanic Caucasians. They are also less likely to have a variant in the nearby MS4A4A locus that has been linked to higher CSF sTREM2. These inheritance patterns translate to African Americans having less sTREM2 in their CSF. This could be important when deciding sTREM2 cutoffs for use as a diagnostic biomarker or an enrollment criterion in clinical trials.

- African Americans more likely carry genetic variants that lower TREM2 expression and processing.

- They produce less soluble TREM2 in their cerebrospinal fluid than do Caucasians.

- This difference should be considered if sTREM2 is to be a biomarker.

“This article is very encouraging because it demonstrates that carefully designed studies can provide valuable insight into [the genetics of] disease pathophysiology despite having relatively smaller sample sizes,” Minerva Carrasquillo, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, wrote to Alzforum (full comment below). “This will be the first of many studies focusing on genetics and biomarkers in more diverse participants,” Carlos Cruchaga, a co-author also at WashU, told Alzforum.

African Americans are twice as likely as Caucasians to get dementia (Dec 2020 news). Yet despite being 13 percent of the U.S. population, they account for 5 percent or less of people enrolled in AD clinical trials and study cohorts. To address this underrepresentation, Morris, Schindler, and colleagues have recruited people from diverse backgrounds to the Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center cohort, which now comprises 19 percent African Americans, and more recently have led efforts to boost minority participation elsewhere (Oct 2018 news). “The racial diversity of the Knight ADRC cohort can serve as an excellent model for other observational cohorts,” Alberto Lleó, Hospital of Sant Pau, Barcelona, Spain, and Marc Suárez-Calvet, BarcelonaBeta Brain Research Center, Spain, wrote to Alzforum (full comment below).

The researchers are starting to accrue enough data to be able to tease out biomarker differences by race. So far, Schindler and colleagues have found less total tau and phosphotau-181 in the CSF of cognitively normal or cognitively impaired African American study participants than in their Caucasian counterparts (Jan 2019 news). Ihab Hajjar, Emory University, Atlanta, found the same in a cohort of people with mild cognitive impairment (Garrett et al., 2019).

What about microglial markers? Previously, researchers reported that sTREM2 creeps up in the CSF of people with AD and that higher levels correlate with slower cognitive decline (Aug 2019 news; Jan 2016 news). Schindler and colleagues wondered if CSF sTREM2 levels differed by race.

To find out, they collected CSF biomarker and genetic information from 91 older African Americans and 868 non-Hispanic Caucasians in the Knight cohort. The majority of participants were cognitively normal—13 percent of African Americans and 25 percent of Caucasians had MCI. There were some notable baseline differences. Compared to the Caucasian participants, African Americans were three years younger on average, had about half a year less education, were less likely to report a family history of dementia, and were less likely to have MCI.

Schindler and colleagues compared participants by self-reported race and by race as determined by the presence of genetic variants traced to African countries or regions. Self-identified race matched genetic ancestry for all but one participant, who was African American; therefore the scientists saw the same trends when grouping participants by either method.

The researchers compared CSF levels of sTREM2, Aβ42, total tau (t-tau), phosphorylated tau 181 (p-tau181), and neurofilament light (NfL) among participants. While amyloid did not differ, sTREM2, t-tau, p-tau181, and NfL were lower in the African Americans. These differences held true after correcting for a plethora of other variables, including age, years of education, family history of dementia, ApoE4 status, and dementia status determined by the clinical dementia rating score.

Were these differences truly linked to race, or could the baseline differences still be the cause, even after correction? To double-check, Schindler and colleagues also used a computer algorithm to match 86 of the 91 African Americans with a Caucasian counterpart who was closest to them in age, years of education, CDR score, and family history of dementia. African Americans still had less CSF sTREM2, t-tau, and p-tau181.

To see if these findings would hold in other cohorts, the researchers collected data on 23 older African Americans and 917 non-Hispanic Caucasians volunteers from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). In this group, African Americans had about a year less education than Caucasians, but were the same on all other demographics. CSF Aβ42, t-tau, p-tau181, and NfL did not differ by race. The researchers attributed this to the cohort size, which may be too small to tease out such subtle differences. Even so, in this small ADNI sample, sTREM2 was lower in African Americans as determined by both self-reported race and genetic ancestry. This difference held true after adjusting for confounders.

Could genetics explain the TREM2 dichotomy? The researchers searched for differences in TREM2 coding variants among the volunteers. In both cohorts, African Americans were five times more likely to have any of these variants than were Caucasians. Schindler also looked at the effect of two single-nucleotide polymorphisms—rs1582763 and rs6591561—around the nearby MS4A4A locus. These SNPs previously had been linked to higher and lower CSF sTREM2, respectively, likely through TREM2 processing differences (Jul 2018 news). Lo and behold, African Americans were 4.6 and 2.3 times less likely to have the sTREM2-boosting rs1582763 in the ADRC and the ADNI cohorts, respectively. The sTREM2-lowering rs6591561 did not differ between groups in either cohort.

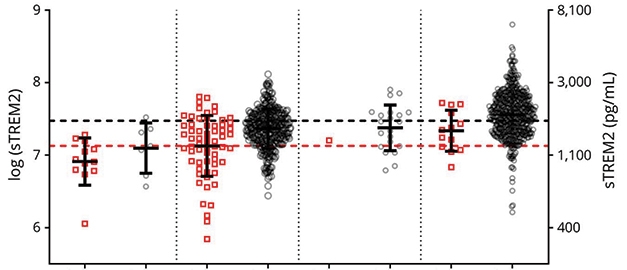

TREM2 Trends. On average, African Americans (red dots) had less sTREM2 (red line) in their CSF than non-Hispanic Caucasians (black dots and line). Left two panels show carriers and noncarriers, respectively, of a TREM2-lowering coding variant. Right two panels show the same, but this time among people who also carried the sTREM2-boosting rs1582763 SNP at the MS4A4A locus. African Americans were more likely to carry the TREM2-suppressing allele and less likely to carry the sTREM2-boosting SNP. [Courtesy of Schindler et al., Neurology Genetics, 2021.]

Did these variants directly relate to CSF sTREM2? Yes. People with a TREM2 coding variant had less sTREM2 in their CSF, while people with the rs1582763 SNP had more (see image above). These relationships remained after correcting for the previously mentioned confounds.

Schindler said the lower CSF sTREM2 levels in African Americans should be considered during diagnosis and treatment. Researchers believe that production of soluble TREM2 reflects microglial activity, and that less sTREM2 means fewer amyloid-clearing microglia. This could make African Americans more susceptible to amyloid pathology. In contrast, less CSF t-tau, p-tau181, and NfL, all markers of neuronal damage, could mean African Americans have less brain damage despite having similar amyloid levels as do Caucasians. This needs to be investigated, the scientists agree.

Researchers believe racial differences in TREM2 biology should also be considered when deciding diagnostic biomarker cut-offs, which are largely based on people of European ancestry. “Genetic variants tied to ancestry influence baseline biomarkers and, ultimately, whether someone is above the diagnostic threshold or not,” Cruchaga said. Lleó agreed. “The heterogeneity of TREM2 function and microglial activity, irrespective of self-identified race, may also contribute to clinical heterogeneity in AD, similar to what we see with tau,” he wrote to Alzforum.

Understanding racial diversity in the underlying biology of Alzheimer's is key to developing safe and effective drugs for everyone, researchers agreed. “If we do not know about biological differences as we design drugs, we may end up with drugs that do not work in African Americans,” Schindler said. This was the case with high blood-pressure medications, which work to varying degrees and with different side effects in African Americans than in Caucasians (Clemmer et al., 2020; Chekka et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2005).

One immediate example is Alector’s anti-TREM2 antibody, AL002. It is currently in Phase 2 for AD. In Phase 1, the antibody lowered sTREM2 in the CSF of people with mild to moderate AD (June 2020 news). “It will be important to investigate whether TREM2 therapies have a different effect in participants with lower TREM2 function,” Lleó and Suárez-Calvet wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Arnon Rosenthal at Alector LLC, South San Francisco, plans to do just that. For the Phase 2 study, the company will retrospectively screen for TREM2 mutations and look at drug efficacy through the lens of mutation carriers and baseline sTREM2 concentration. He said Alector also aims to broaden participant diversity. “We are opening additional clinical sites in places like Atlanta and Baltimore to make accessing the trial easier,” Rosenthal told Alzforum.

Mark Gluck and his group are building a research cohort of older African Americans at Rutgers University in Newark, New Jersey. They have not yet looked at TREM2 in the more than 400 people they have genotyped so far. “Based on this paper, we will add TREM2 to all our future analyses, especially as we begin new studies of immune health and COVID-19 history,” Gluck wrote to Alzforum (comment below).—Chelsea Weidman Burke

References

News Citations

- In the United States, Racial Disparities in Dementia Risk Persist

- Alzheimer’s Researchers Seek Advice on How to Include African-Americans

- Do Alzheimer’s Biomarkers Vary by Race?

- In Alzheimer’s, More TREM2 Is Good for You

- TREM2 Goes Up in Spinal Fluid in Early Alzheimer’s

- MS4A Alzheimer’s Risk Gene Linked to TREM2 Signaling

- In Mice, Activating TREM2 Tempers Plaque Toxicity, not Load

Therapeutics Citations

Paper Citations

- Garrett SL, McDaniel D, Obideen M, Trammell AR, Shaw LM, Goldstein FC, Hajjar I. Racial Disparity in Cerebrospinal Fluid Amyloid and Tau Biomarkers and Associated Cutoffs for Mild Cognitive Impairment. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Dec 2;2(12):e1917363. PubMed.

- Clemmer JS, Pruett WA, Lirette ST. Racial and Sex Differences in the Response to First-Line Antihypertensive Therapy. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7:608037. Epub 2020 Dec 17 PubMed.

- Chekka LM, Chapman AB, Gums JG, Cooper-DeHoff RM, Johnson JA. Race-Specific Comparisons of Antihypertensive and Metabolic Effects of Hydrochlorothiazide and Chlorthalidone. Am J Med. 2021 Jan 9; PubMed.

- Wu J, Kraja AT, Oberman A, Lewis CE, Ellison RC, Arnett DK, Heiss G, Lalouel JM, Turner ST, Hunt SC, Province MA, Rao DC. A summary of the effects of antihypertensive medications on measured blood pressure. Am J Hypertens. 2005 Jul;18(7):935-42. PubMed.

External Citations

Further Reading

Papers

- Jin SC, Carrasquillo MM, Benitez BA, Skorupa T, Carrell D, Patel D, Lincoln S, Krishnan S, Kachadoorian M, Reitz C, Mayeux R, Wingo TS, Lah JJ, Levey AI, Murrell J, Hendrie H, Foroud T, Graff-Radford NR, Goate AM, Cruchaga C, Ertekin-Taner N. TREM2 is associated with increased risk for Alzheimer's disease in African Americans. Mol Neurodegener. 2015 Apr 10;10:19. PubMed.

Primary Papers

- Schindler SE, Cruchaga C, Joseph A, McCue L, Farias FH, Wilkins CH, Deming Y, Henson RL, Mikesell RJ, Piccio L, Llibre-Guerra JJ, Moulder KL, Fagan AM, Ances BM, Benzinger TL, Xiong C, Holtzman DM, Morris JC. African Americans Have Differences in CSF Soluble TREM2 and Associated Genetic Variants. Neurol Genet. 2021 Apr;7(2):e571. Epub 2021 Mar 4 PubMed. Correction.

- Lleó A, Suárez-Calvet M. Race and Alzheimer Disease Biomarkers: A Neglected Race. Neurol Genet. 2021 Apr;7(2):e574. Epub 2021 Mar 4 PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

Rutgers Biomedical & Health Sciences

The work by Schindler and colleagues at the Knight ADRC adds to the growing number of studies showing CSF biomarker levels to differ between racial groups. Such studies—including our own—have been criticized in the past for highlighting how a social construction, i.e., race, can result in biological outcomes. The Knight ADRC investigators incorporated both self-reported race and genetic ancestry in their study, and found extremely high concordance between self-reported African American race and African genetic ancestry. This high level of concordance prevented a statistical determination of which was most strongly associated with lower CSF sTREM2 levels, but they further investigated the relationship between TREM2 genotype and sTREM2 levels. They found that more coding TREM2 variants in African Americans linked to lower sTREM2 levels, and less often than another variant associated with higher sTREM2 levels.

I believe this study contributes to our understanding of AD disparities in three ways. First, the imbalance between African Americans and whites in gene variants related to Alzheimer’s disease risk supports the notion that genetic ancestry may selectively influence risk-conferring or protective pathways. If therapeutic strategies targeting TREM2 are to be tested in the future, sufficient numbers of African Americans must be included to adequately assess the treatment’s impact in this subgroup. Second, some CSF biomarkers and their associated genes are tightly connected, and we have seen a similar relationship between APOE genotype and CSF ApoE protein levels.

Changes in these CSF biomarker levels will need to be adjusted for genotypes, which is not often done. Finally, it is not always straightforward to disentangle the social aspects of race from genetic ancestry using traditional statistical modeling, and more innovative methods are necessary to better understand Alzheimer’s disease risks from biological and sociological factors.

Rutgers University-Newark,

This Schindler et al. paper is an important and welcome contribution to the field for two reasons.

First, it highlights the importance of understanding how genetic variations that influence risk for AD differ in African Americans as compared to non-Hispanic whites. A growing literature suggests that two other genetic risk factors for AD, APOE and ABAC7, function differently in those of African descent, both in terms of their direct linkage to AD as well as in their interaction with behavioral and health factors (for review, see our paper, Berg et al., 2019). The Schindler et al. paper, however, is the first to show that variations in TREM2 may also differ in African Americans. Based on their findings, we plan to add assessing for variations in TREM2 to our own ongoing studies of Pathways to Healthy Aging in African Americans in Newark, N.J.

Second, this paper further illuminates the intriguing, but still not fully understood, role of immune system dysfunction in AD. Although there is increasing evidence that AD involves disruption to the immune system, we do not sufficiently understand the degree to which AD pathology and risk are related to immune system dysfunction. The Schindler et al. study will encourage further work in this area, especially with regard to elucidating links between TREM2, immune health, cognitive and brain health, and AD risk.

References:

Berg CN, Sinha N, Gluck MA. The Effects of APOE and ABCA7 on Cognitive Function and Alzheimer's Disease Risk in African Americans: A Focused Mini Review. Front Hum Neurosci. 2019;13:387. Epub 2019 Nov 5 PubMed.

Alector

Alector

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) was reported to be ~14 percent to 100 percent more prevalent among African Americans (AAs) compared to non-Hispanic whites (NHWs). The increased AD risk in AA is partially attributed to high cholesterol, high blood pressure, Type 2 diabetes, and vascular dementia, which are present disproportionately in AA, and constitute significant risk factors for AD (African-Americans and Alzheimer's Disease: The Silent Epidemic).

Here, Schindler et al. provide original mechanistic and genetic insights into the higher prevalence of AD among AAs, and open the perspective of targeted therapeutics for AAs suffering from the disease.

By studying two large cohorts of mixed ethnicity, Schindler et al. observed that cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of soluble TREM2 (sTREM2) are almost 30 percent lower in AAs compared to NHWs.

CSF sTREM2 is a highly relevant AD biomarker, because lower levels were previously linked to an increase in AD risk, a decrease in the age of AD onset, rapid loss of cortical and hippocampal volume in AD subjects, lower survival in symptomatic AD, higher rate of conversion from MCI to AD, and faster disease progression (Ewers et al., 2019; Gispert et al., 2016).

Schindler et al. also noted that rare TREM2 coding genetic variants and an MS4A4A noncoding genetic variant known to be associated with lower CSF sTREM2 levels are respectively five- and two- to fourfold more frequent in AAs, and showed that such higher prevalence of those variants in AA may explain the lower CSF sTREM2 levels observed in this population.

TREM2 and MS4A4A are key risk genes for AD that regulate the survival, proliferation, migration, and functionality of microglia, the disease-fighting, innate immune cells in the AD brain (Ulland and Colonna, 2018; Deming et al., 2019). The levels of sTREM2 are believed to reflect TREM2 and/or MS4A4A activity in microglia (Ewers et al., 2019; Deming et al., 2019).

Low levels of sTREM2 in the CSF of AA thus likely reflect a decreased functionality of the disease-fighting microglia. Fewer and/or disabled microglia are in turn less likely to counteract multiple AD pathogenic events, including the accumulation of Aβ and Tau, neuronal dystrophy, synaptic loss, and micro-hemorrhages.

The findings of likely defects in TREM2 and MS4A4A functions in AA, as manifested by the low levels of sTREM2, not only provide a possible mechanistic explanation for the prevalence of AD in AAs, but also suggest that AAs may respond differently, and possibly more robustly, to both TREM2 activation therapy and to MS4A4A therapies that would increase the level of sTREM2. The findings may thus open a new and exciting chapter in precision medicine for AD that is based on a deep understanding of human genetics and disease mechanisms.

A TREM2-activating investigational therapeutic is currently in a Phase 2 clinical trial for AD (INVOKE-2), and an MS4A4A investigational therapeutic is advancing toward the clinic in AD. Both investigational therapeutics are sponsored by Alector Inc. as part of the company’s broad immuno-neurology platform.

For both our TREM2 and MS4A (did not start yet) trials, we intend to retrospectively analyze for the presence of the TREM2 and MS4A4A mutations and stratify mutation carriers as well as the levels of sTrem2 at baseline to the magnitude of drug efficacy. This will help with the design and patient stratification of our Phase 3.

The participation of AA in AD trials was historically low (Donanemab Phase 2: 3 percent; Aducamab Emerge/Engage: ~5 percent, they only report white and Asian; Solanezumab: ~1.7 percent), but Glenn Morrison, VP, our lead clinician for TREM2, is looking for ways to change that with our Phase 2 Trem2 (INVOKE-2) trial by opening additional clinical sites in places such as Atlanta and Baltimore, to make access easier.

References:

Ewers M, Franzmeier N, Suárez-Calvet M, Morenas-Rodriguez E, Caballero MA, Kleinberger G, Piccio L, Cruchaga C, Deming Y, Dichgans M, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM, Weiner MW, Haass C, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Increased soluble TREM2 in cerebrospinal fluid is associated with reduced cognitive and clinical decline in Alzheimer's disease. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Aug 28;11(507) PubMed.

Gispert JD, Suárez-Calvet M, Monté GC, Tucholka A, Falcon C, Rojas S, Rami L, Sánchez-Valle R, Lladó A, Kleinberger G, Haass C, Molinuevo JL. Cerebrospinal fluid sTREM2 levels are associated with gray matter volume increases and reduced diffusivity in early Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2016 Dec;12(12):1259-1272. Epub 2016 Jul 14 PubMed.

Ulland TK, Colonna M. TREM2 - a key player in microglial biology and Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018 Nov;14(11):667-675. PubMed.

Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville

Differences in the levels of CSF Aβ and tau biomarkers in African Americans vs. non-Hispanic whites have been previously reported. This article from Schindler et al. provides evidence that CSF sTREM2 levels are lower in African Americans compared to non-Hispanic whites, and that this may be due to a higher frequency in African Americans of TREM2 variants that are associated with lower CSF sTREM2.

Taken together these findings underscore the importance of studying cohorts from diverse populations to ensure that effective therapies are developed by taking these differences into consideration.

In addition, this article is very encouraging for those of us conducting research focused on health disparities in underrepresented groups, as it demonstrates that, through carefully designed studies, it is possible to obtain valuable insight into the pathophysiology of disease, despite the challenge of having access to relatively smaller sample sizes.

BarcelonaBeta Brain Research Center; Hospital del Mar - Barcelona

Hospital de Sant Pau

Schindler et al. compared the levels of CSF soluble TREM2 (sTREM2) between African Americans (AA) and non-Hispanic whites (NHW), based on self-reported race and ethnicity. Interestingly, they found that CSF sTREM2 was lower in AA compared to NHW. This difference was probably explained by the fact that coding TREM2 variants associated with lower CSF sTREM2 (Piccio et al., 2016; Suárez-Calvet et al., 2019) were more frequent in AA. On the contrary, AA were less likely to carry the rs1582763 minor allele (A), located near MS4A4A, which is associated with higher CSF sTREM2 (Deming et al., 2019).

CSF sTREM2 reflects the amount of TREM2 competent signaling on the surface of microglia (Kleinberger et al., 2014) and higher CSF sTREM2 concentrations are associated with reduced cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (Ewers et al., 2019). The heterogeneity in CSF sTREM2 levels (and TREM2 function and microglial activity) may contribute to the clinical heterogeneity in Alzheimer’s disease, irrespective of self-identified race and ethnicity. Therapies that target TREM2 are currently being developed and it will be important to assess whether these therapies have a different effect in participants with a lower TREM2 function.

This study also reminds us about the importance of investigating the associations between biomarkers and race, and that race is a social construct with profound effects on health, including Alzheimer’s disease. Although some genetic variants are more frequently found in certain self-identified racial and ethnic groups, there are non-biological factors (e.g., social, economic, environmental) that also need to be considered. We must strengthen diversity in Alzheimer’s observational studies and clinical trials. The racial diversity of the Knight ADRC cohort can serve as an excellent model for other observational AD cohorts.

References:

Deming Y, Filipello F, Cignarella F, Cantoni C, Hsu S, Mikesell R, Li Z, Del-Aguila JL, Dube U, Farias FG, Bradley J, Budde J, Ibanez L, Fernandez MV, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Heslegrave A, Johansson PM, Svensson J, Nellgård B, Lleo A, Alcolea D, Clarimon J, Rami L, Molinuevo JL, Suárez-Calvet M, Morenas-Rodríguez E, Kleinberger G, Ewers M, Harari O, Haass C, Brett TJ, Benitez BA, Karch CM, Piccio L, Cruchaga C. The MS4A gene cluster is a key modulator of soluble TREM2 and Alzheimer's disease risk. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Aug 14;11(505) PubMed.

Ewers M, Franzmeier N, Suárez-Calvet M, Morenas-Rodriguez E, Caballero MA, Kleinberger G, Piccio L, Cruchaga C, Deming Y, Dichgans M, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM, Weiner MW, Haass C, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Increased soluble TREM2 in cerebrospinal fluid is associated with reduced cognitive and clinical decline in Alzheimer's disease. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Aug 28;11(507) PubMed.

Kleinberger G, Yamanishi Y, Suárez-Calvet M, Czirr E, Lohmann E, Cuyvers E, Struyfs H, Pettkus N, Wenninger-Weinzierl A, Mazaheri F, Tahirovic S, Lleó A, Alcolea D, Fortea J, Willem M, Lammich S, Molinuevo JL, Sánchez-Valle R, Antonell A, Ramirez A, Heneka MT, Sleegers K, van der Zee J, Martin JJ, Engelborghs S, Demirtas-Tatlidede A, Zetterberg H, Van Broeckhoven C, Gurvit H, Wyss-Coray T, Hardy J, Colonna M, Haass C. TREM2 mutations implicated in neurodegeneration impair cell surface transport and phagocytosis. Sci Transl Med. 2014 Jul 2;6(243):243ra86. PubMed.

Piccio L, Deming Y, Del-Águila JL, Ghezzi L, Holtzman DM, Fagan AM, Fenoglio C, Galimberti D, Borroni B, Cruchaga C. Cerebrospinal fluid soluble TREM2 is higher in Alzheimer disease and associated with mutation status. Acta Neuropathol. 2016 Jun;131(6):925-33. Epub 2016 Jan 11 PubMed.

Suárez-Calvet M, Morenas-Rodríguez E, Kleinberger G, Schlepckow K, Araque Caballero MÁ, Franzmeier N, Capell A, Fellerer K, Nuscher B, Eren E, Levin J, Deming Y, Piccio L, Karch CM, Cruchaga C, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Weiner M, Ewers M, Haass C, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Early increase of CSF sTREM2 in Alzheimer's disease is associated with tau related-neurodegeneration but not with amyloid-β pathology. Mol Neurodegener. 2019 Jan 10;14(1):1. PubMed.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.