In the Running: Trial Results from CTAD Conference

Quick Links

Researchers presented a fall crop of Phase 1 results at the recent Clinical Trials in Alzheimer’s Disease meeting, held November 1–4 in Boston. New treatments aimed at neurotrophin signaling, tau, and cholinergic pathways moved on to Phase 2, where their sponsors face decisions about which biomarkers are worth their price tag.

- The neurotrophin receptor activator LM11A-31 moves to Phase 2.

- So do tau antibody BIIB092 and phosphodiesterase inhibitor BPN14770.

- Which biomarkers should small drug programs use?

LM11A-31

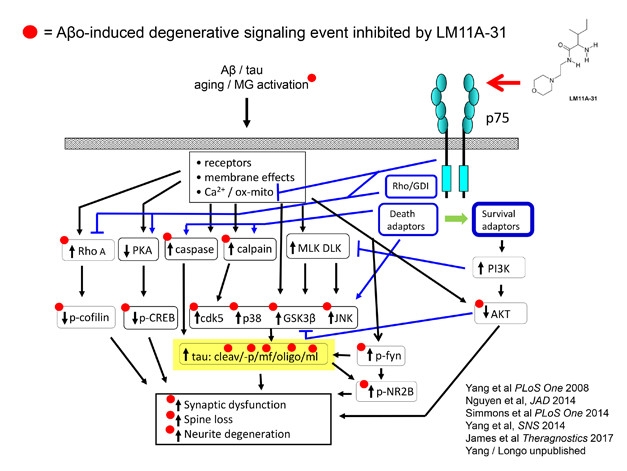

Sandwiched between toxic Aβ and tau proteins on one side, and synaptic dysfunction and neurite loss on the other, lies a complex web of neuronal middlemen. Think G proteins, kinases, proteases, transcriptional activators, and cytoskeletal proteins. How best to intervene when the target is not one pathway or mediator, but many? Frank Longo of Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, proposes that one answer could be LM11A-31, an activator of the p75 neurotrophin receptor. A top-level regulator of synapse life and death in the nervous system, p75’s own signaling network overlaps with those of Aβ and tau.

LM11A-31, a brain-penetrant small molecule that can be taken by mouth, boosts the pro-synaptic effects of p75 and antagonizes Aβ and tau signaling at multiple points. In animal models, LM11A counteracts the toxicity of Aβ and tau to prevent synaptic dysfunction, spine loss, neurite degeneration, microglia activation, and cognitive deficits (Knowles et al., 2013; Nguyen et al., 2014; James et al., 2017). The compound appears to reverse degeneration in 12-month-old AD mice (Simmons et al., 2014). New work presented at CTAD suggested that LM11A-31 repairs age-related loss of cholinergic neurons in wild-type mice, Longo told the audience.

Tweak a Tangled Web. LM11A-31 activation of the p75 neurotrophin receptor protects synapses by way of interfering with Aβ- and tau-induced signaling. [Courtesy of Frank Longo.]

In a Phase 1 trial, single or multiple doses of LM11A-31 taken by young or old volunteers produced no adverse events and were well tolerated. This study has now cleared the way for an international multicenter Phase 2a trial sponsored by Longo’s company, PharmatropiX, Inc., Menlo Park, California, and supported by the NIA and philanthropic funding. The trial aims to treat at least 180 mild to moderate AD patients with a low or a high dose of LM11A-31, or placebo, for 26 weeks. The primary endpoint will be safety; exploratory endpoints include a cognitive battery, CSF biomarkers, and FDG-PET.

After a low-key early development phase, LM11A-31 recently nabbed John Harrison of Metis Cognition Ltd., U.K., to help with cognitive assessments, University of Gothenberg’s Kaj Blennow for biomarker measurement, as well as Manfred Windisch at NeuroScios, St. Radegund/Graz, Austria, and Niels Andreasen and Agneta Nordberg of the Karolinska Institute in Solna, Sweden, to oversee the Phase 2a trial, Longo said at CTAD.

BIIB092

An approach to target tauopathy is advancing in the clinic, as well. Irfan Qureshi, now at Biohaven Pharmaceuticals of New Haven, Connecticut, at CTAD presented a poster on the humanized monoclonal tau antibody BIIB092. While at Bristol-Myers Squibb, Qureshi worked on this antibody, formerly known as BMS-986168. It recognizes N-terminal fragments of tau (aka eTau), which are secreted from neurons and end up in brain interstitial fluid and CSF. In mouse models of AD, the antibody lowered CSF eTau, and decreased tau-induced neuronal hyperexcitability and amyloid pathology (Bright et al., 2015). It also reportedly reduced tau toxicity in mouse models of frontotemporal dementia (Nov 2012 news). While the precise role of eTau is unclear, one idea is that it might be involved in propagating pathology from cell to cell.

Qureshi examined what ascending doses of BIIB092 would do to CSF eTau in PSP. Forty-eight participants received doses of up to 2,100 mg, infused once every four weeks for 12 weeks. The investigators saw no more adverse events in any dose than in placebo. Most events were mild, and none led to discontinuation. The antibody showed a dose-dependent accumulation in serum and CSF. Importantly, it generated a marked reduction in CSF free eTau that exceeded 90 percent for all doses. Reductions averaged 90–96 percent after 39 days of treatment, and 91–97 percent after 85 days. The investigators concluded that the antibody was safe, well tolerated, and engaged its target.

Biogen has licensed BIIB092 from Bristol-Myers Squibb, and is conducting an efficacy study in patients with PSP. The company is now developing plans for an additional Phase 2 efficacy study in Alzheimer’s disease.

BPN14770

Mark Gurney, Tetra Discovery Partners, Grand Rapids, Michigan, presented preclinical and human Phase 1 results for BPN14770, an allosteric inhibitor of the enzyme phosphodiesterase 4D (PDE4D). In the brain, PDE4D inhibitors boost cAMP, a second messenger for acetylcholine. BPN14770 hits the same pathway as acetyl cholinesterase inhibitors such as donepezil, though at a point farther downstream. Gurney and colleagues designed BPN14770 based on the PDE4D crystal structure, to try to remove a dose-limiting side effect of previous inhibitors that induced vomiting (Burgin et al., 2010).

Getting preclinical data on BPN14770 required a special effort in mouse models, Gurney said. Mouse and human PDE4D differ at a critical amino acid in the active site, and inhibitors tailored to the human enzyme are much less potent in mice. To clear that hurdle, Gurney created a mouse whose PDE4D DNA sequence was altered to match the human enzyme. Gurney showed that in these humanized mice, but not their wild-type counterparts, low doses of BPN14770 increased brain cAMP, enhanced hippocampal long-term potentiation, and improved performance in the 24-hour novel object recognition test for long-term memory. Dosing for two weeks boosted hippocampal phospho-CREB and BDNF, markers of long-term memory consolidation.

A PET ligand to PDE4D is available. In primates, it binds to brain regions important for memory and cognition, including the hippocampus and the entorhinal and prefrontal cortices. Gurney showed that BPN14770 displaced binding of this tracer, giving an estimated target occupancy rate of 83 percent for the drug in pertinent brain regions.

In a Phase 1 trial, 32 healthy volunteers received ascending doses of up to 100 mg BPN14770. Although some vomited on the 100 mg dose, there was no such distress on lower doses that still maintained pharmacologically active blood levels. Multiday dosing in both young and old volunteers produced the same pharmacokinetics, and older participants tolerated the drug well, without nausea, vomiting, or CNS effects at doses of 10, 20, or 40 mg, Gurney showed.

Even in this small trial, the drug did cause a measurable memory enhancement, Gurney claimed. Older adults treated for seven days improved their response times in the One Card Back test compared to the placebo group. The effect showed up immediately after the first treatment, and continued for the week.

BPN14770 will now advance to a Phase 2 trial in 180 patients with early AD. Gurney said he expects to see improvements in short-term, and perhaps also long-term memory. “The compound modulates a fundamental mechanism of memory. It is not amyloid-directed, and should work regardless of cholinergic deficits,” he told Alzforum.

VU319

Another cognitive enhancer entered Phase 1 testing shortly before CTAD, reported Paul Newhouse of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. VU319 is an allosteric modulator of the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor that is being developed at Vanderbilt, with Phase 1 funding from the Alzheimer’s Association and the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation. Newhouse showed quantitative EEG and event-related potential readouts that he will implement in the trial to judge target engagement and drug effects. He also investigates nicotinic acetylcholine activation in cognition, and recently started the Memory Improvement Through Nicotine Dosing (MIND), a two-year trial that asks whether long-term treatment with a nicotine patch improves memory and function in adults with mild cognitive impairment.

To Scan or Not to Scan …

As sponsors advance their investigational drugs, they have to decide which biomarkers to use. It can be a tough call for a small company on a budget.

Biomarkers have become de rigueur in the field; indeed, one argument holds that every drug trial should include AD biomarkers not only to better show what the drug did but also to help build a collective knowledge base tying biomarker change to disease progression and to drug response. Most researchers agree that future trial populations should be characterized with biomarkers so that results can be more fully understood. Good biomarker data can make the difference between a negative but valuable and an uninterpretable, i.e. failed, trial.

For example, adding amyloid positivity at screening to ascertain the diagnosis has become a nearly standard inclusion criterion for AD trials over the past five years. This practice followed revelations that about a third of ApoE4 noncarriers in the first solanezumab Phase 3 trials, and also in ADNI, were amyloid-negative. These participants were then thought to have had a disease other than AD.

But some scientists are pushing back. They question whether biomarkers, at least expensive ones such as PET, are always worth the expense. This is controversial among trialists, but some say the clinical diagnosis itself has improved somewhat in recent years. Take Merck’s EPOCH trial of verubecestat in mild to moderate AD (see Part 6 of this series). Its inclusion criteria did not require amyloid positivity, but even so, 90 percent of participants were amyloid-positive in both a flutemetamol PET and a CSF sub-study, each containing 21 people whose demographics were representative of the overall trial population. “This suggests that the clinical diagnosis was not so bad in this trial,” Mike Egan of Merck in Pennsylvania told the CTAD audience.

Similarly, Lon Schneider of University of Southern California, Los Angeles, reported that in a negative Phase 2 trial of edonerpic, aka T-817, 98 percent of clinically diagnosed participants turned out to be biomarker positive (see Part 12 of this series).

And Tobias Hartmann of Saarland University, Homburg, Germany, presented a new analysis done with Pieter Jelle Visser of Maastricht University in the Netherlands and the University of Gothenberg's Blennow, which hinted at much the same. These scientists asked how the prodromal AD population enrolled into the negative treatment trial of the medical food Souvenaid (Nov 2017 news) would have fared had it been classified with newer diagnostic criteria published after this trial started. “In this trial, most of our patients were included not based on CSF or pathology markers, but based on structural MRI. MRI was available, and participants readily agreed to do it,” Hartmann told the CTAD audience. However, many patients in this trial donated CSF, as well, and when reclassified according to new criteria that require Aβ/tau biomarker information, 91 percent of the enrolled patients ended up with the same diagnosis. “We did not expect this large overlap. I thought CSF would make more difference. That is encouraging. It is not as if you always have to have amyloid CSF or PET,” Hartmann said.

Other scientists agreed. “We can do some future mild to moderate AD trials without this expense,” said Bruno Vellas of Gerontopole in Toulouse, France. And Lawrence Honig of Columbia University in New York told Alzforum, “Maybe the clinical diagnosis is less defective than one might think. Perhaps it is not always critical to ascertain amyloid positivity, especially when it is unavailable or too costly.” —Pat McCaffrey and Gabrielle Strobel

References

News Citations

- SfN: Tau Toxicity in the Limelight

- Verubecestat Negative Trial Data: What Does it Mean for BACE Inhibition?

- At Least We Know These Don’t Work: Negative Trials at CTAD

- LipiDiDiet Data Published

Therapeutics Citations

Paper Citations

- Knowles JK, Simmons DA, Nguyen TV, Vander Griend L, Xie Y, Zhang H, Yang T, Pollak J, Chang T, Arancio O, Buckwalter MS, Wyss-Coray T, Massa SM, Longo FM. A small molecule p75NTR ligand prevents cognitive deficits and neurite degeneration in an Alzheimer's mouse model. Neurobiol Aging. 2013 Aug;34(8):2052-63. PubMed.

- Nguyen TV, Shen L, Vander Griend L, Quach LN, Belichenko NP, Saw N, Yang T, Shamloo M, Wyss-Coray T, Massa SM, Longo FM. Small molecule p75NTR ligands reduce pathological phosphorylation and misfolding of tau, inflammatory changes, cholinergic degeneration, and cognitive deficits in AβPP(L/S) transgenic mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42(2):459-83. PubMed.

- James ML, Belichenko NP, Shuhendler AJ, Hoehne A, Andrews LE, Condon C, Nguyen TV, Reiser V, Jones P, Trigg W, Rao J, Gambhir SS, Longo FM. [(18)F]GE-180 PET Detects Reduced Microglia Activation After LM11A-31 Therapy in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer's Disease. Theranostics. 2017;7(6):1422-1436. Epub 2017 Mar 24 PubMed.

- Simmons DA, Knowles JK, Belichenko NP, Banerjee G, Finkle C, Massa SM, Longo FM. A small molecule p75NTR ligand, LM11A-31, reverses cholinergic neurite dystrophy in Alzheimer's disease mouse models with mid- to late-stage disease progression. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e102136. Epub 2014 Aug 25 PubMed.

- Bright J, Hussain S, Dang V, Wright S, Cooper B, Byun T, Ramos C, Singh A, Parry G, Stagliano N, Griswold-Prenner I. Human secreted tau increases amyloid-beta production. Neurobiol Aging. 2015 Feb;36(2):693-709. Epub 2014 Sep 16 PubMed.

- Burgin AB, Magnusson OT, Singh J, Witte P, Staker BL, Bjornsson JM, Thorsteinsdottir M, Hrafnsdottir S, Hagen T, Kiselyov AS, Stewart LJ, Gurney ME. Design of phosphodiesterase 4D (PDE4D) allosteric modulators for enhancing cognition with improved safety. Nat Biotechnol. 2010 Jan;28(1):63-70. PubMed.

Other Citations

External Citations

Further Reading

No Available Further Reading

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.