CONFERENCE COVERAGE SERIES

Alzheimer's Association International Conference 2011

Paris, France

16 – 21 July 2011

CONFERENCE COVERAGE SERIES

Paris, France

16 – 21 July 2011

After disappointing trial results for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) drugs, all eyes are on the Phase 3 clinical trials of two monoclonal antibodies to amyloid-β: bapineuzumab, developed by Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy and Pfizer, and solanezumab, by Eli Lilly and Company. We will have to hold our collective breath a little longer for the results, which should be available at around the same time for both trials.

Although there were several bapineuzumab presentations at the 2011 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC, formerly ICAD), held 16-21 July in Paris, France, none shed new light on the all-important efficacy front. They did, however, suggest (for those looking for some good news) that the ongoing Phase 3 trials are unlikely to be derailed by safety concerns. In the process, they recast what was earlier thought to be a potentially show-stopping side effect of amyloid-targeting therapies into one that actually indicates the therapy is working.

When given intravenously to patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease, bapineuzumab has been shown by PET to decrease brain amyloid (see ARF related news story on Rinne et al., 2010). But the treatment also raised concern when some patients enrolled in the Phase 2 trial developed vasogenic edema—an abnormal accumulation of fluid—and tiny hemorrhages in the brain (see ARF related news story on Salloway et al., 2009 and ARF related news story).

At AAIC, scientists reported results of a re-evaluation of the Phase 2 safety data of bapineuzumab and of an ongoing long-term extension trial of a subset of patients enrolled in the Phase 2 trial. They revealed that these abnormalities are widespread among patients receiving bapineuzumab, but they appear “manageable,” according to Stephen Salloway of Butler Hospital and Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, one of the clinical investigators involved in the bapineuzumab trials. “What we have learned about dosing and risk factors is helping us manage the vascular edema,” Salloway told ARF. “We have found that most cases are relatively mild and transient. Most people with vascular edema can be re-dosed and can then resume treatment. So this is something we can manage.”

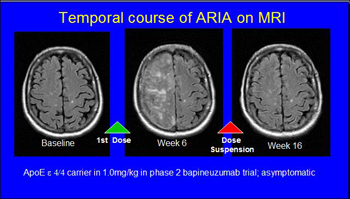

Series of MR scans of an AD patient who developed temporary ARIA without clinical symptoms while on bapineuzumab. View larger image. Image credit: Stephen Salloway and Reisa Sperling

If Not Music, Then What Is "ARIA"?

A working group of academic and industry experts, established by the Alzheimer’s Association to help guide the conduct of clinical trials of amyloid-lowering treatments for AD, renamed abnormalities corresponding to vasogenic edema and microhemorrhages, which are typically detected on MRI scans, as amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA)-E and ARIA-H, respectively (Sperling et al., 2011). “Vasogenic edema has radiological connotations of being tumor and abscess related,” said Salloway in a presentation on Thursday, 21 July, at AAIC. Changing the name would help identify the condition as a distinct phenomenon associated with AD and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA)—the deposition of amyloid-β on the walls of blood vessels in the brain.

Microhemorrhages (or ARIA-H) occur as a result of healthy aging and in AD patients. In a presentation at AAIC, Meike Vernooij of Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, The Netherlands, estimated that such abnormalities may be found in 3 to 15 percent of healthy older adults and in 18 to 32 percent of patients with AD. “The wide range of estimates reflects the fact that it depends on what tools and techniques you use,” said Vernooij. Although prevalence figures are unavailable for ARIA-E, some studies presented at AAIC suggest that it might also occur in some AD patients in the absence of treatment.

Although ARIA may occur “naturally” in some AD patients, there is no doubt that medications such as bapineuzumab hasten its development—and scientists now have some mechanistic hints as to why. At AAIC, Sally Schroeter and Wagner Zago, two researchers at Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy, presented a poster suggesting that bapineuzumab treatment causes blood vessels to become leaky due to the movement of amyloid-β from plaques in the brain into and then out of blood vessel walls. When 15–21-month-old PDAPP transgenic mice (see PDAPP line109) were treated weekly with a murine form of bapineuzumab for up to 36 weeks, blood vessel walls became temporarily weakened precisely at sites where Aβ had been deposited. During early stages of treatment, amyloid-β moves from the parenchyma to blood vessel walls. As Aβ is then removed from blood vessels, fluid leaks out. Aβ moves to the capillaries, where “it reduces the function of the water channel aquaporin AQ4,” Zago told ARF. “But eventually, the normal vascular integrity is restored.”

These results may explain how the side effects seen in AD patients treated with bapineuzumab occur. In his presentation, Salloway showed MRI results from one AD patient who participated in the Phase 2 bapineuzumab trial. In those images, the location of ARIA-E corresponded precisely to sites with high amounts of amyloid deposition. A follow-up MRI in the same patient showed that both the ARIA-E and amyloid were gone.

ARIA by the Numbers

The Phase 2 trial of bapineuzumab was an 18-month-long, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multiple ascending dose trial of 234 patients randomized to receive one of four doses of drug by intravenous infusion every 13 weeks. (It was carried out by the pharmaceutical companies Elan and Wyeth, but since then, Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy, a newly formed subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson, purchased Elan’s AD immunotherapy program and Pfizer bought Wyeth.)

Reisa Sperling of Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, one of the clinical investigators involved in the Phase 2 bapineuzumab trial, presented results at AAIC 2011 of a re-evaluation of more than 2,000 MRI scans taken during the trial. “We realized the ability to recognize ARIA-E has evolved over time, so we suspected there might have been some missed cases,” said Sperling. “We also wanted to do a more systematic analysis of the data.”

The researchers identified 36 people (about 17 percent of the 210 trial participants who received treatment) whose MRI scans showed ARIA-E that the scientists thought was brought on by bapineuzumab; in other words, the abnormalities were absent at baseline and detected post-treatment. In 21 of those patients, ARIA-E had been identified during the Phase 2 trial. The additional 15 people with ARIA-E identified by Sperling’s re-evaluation had escaped detection in the original trial. “They had more subtle MRI changes, which may explain why they were missed,” said Sperling. None of these 15 patients had symptoms related to the ARIA-E, which can include headaches, loss of coordination, and disorientation. Many of the patients with ARIA-E (17 out of 36) also had ARIA-H that occurred during the trial (incident ARIA-H), indicating that the two conditions are related; incident ARIA-H was detected in only seven of the patients who did not have ARIA-E.

Although the prevalence of ARIA-E is high among patients receiving bapineuzumab, the fact that many patients did not have clinical symptoms related to the condition is reassuring to Sperling. “Those people continued to be treated throughout the trial because the ARIA-E was not detected, and they remained asymptomatic,” said Sperling. “I think that stopping therapy for patients who show evidence of ARIA-E makes sense. But on the other hand, if there are very mild cases and they get missed, we know from these data that we are probably not causing terrible harm to patients.”

Consistent with earlier studies, Sperling’s re-evaluation of the MRI data showed that patients with the apolipoprotein E4 allele (ApoE4) and those receiving the highest dose (2 mg/kg) of bapineuzumab were more likely to show evidence of ARIA-E. “There are no surprises here,” said Sid Gilman at the University of Michigan, commenting on an abstract of Sperling’s presentation. (The 2 mg/kg dose was dropped in the Phase 3 trials to minimize ARIA-E. For more information, see ARF related news story).

There were also few surprises in the interim results, presented by Salloway, on the ongoing long-term open-label extension study of 194 patients who continued to receive bapineuzumab after they completed the blinded Phase 2 trial. (Some subjects in the study who were originally receiving 2.0 mg/kg of the drug were switched to 1.0 mg/kg in the extension trial.) At the time of Salloway’s presentation, 94 people had received bapineuzumab treatment for at least three years, 43 for at least four years, and 22 for at least five years. The extension trial is expected to continue until the Phase 3 results are in.

Most participants (95 percent) reported a wide array of adverse events, including falls, agitation, urinary tract infections, upper respiratory tract infections, and anxiety. About 24 percent of patients reported adverse events that Salloway and colleagues tied to bapineuzumab treatment. The most common of those was ARIA-E, which occurred in 9.3 percent of patients. “The most encouraging result from this long-term study is that there are no new safety issues,” said Salloway.

Among the 18 patients with ARIA-E, two had headaches and other symptoms related to this condition, while the rest were asymptomatic. In addition, the risk of developing ARIA-E diminished as people received more infusions of the drug. The cumulative risk of developing ARIA-E dropped from 6.7 percent for infusions 1 to 3 to 2.7 percent for infusions 4 to 10. “This result,” said Salloway, “sheds light on the mechanism of action of bapineuzumab.” The interpretation is that the treatment-related edema develops early on as large quantities of pre-existing amyloid are being mopped up by the antibody and then occurs less frequently once more amyloid has been cleared.

This mechanism would explain why ApoE4 carriers, who have higher amounts of Aβ in their brains and blood vessels, are more prone to ARIA-E. It also explains why higher doses of the drug, inducing greater Aβ clearance, would increase the risk for ARIA-E.

Not Just Bapi: ARIA Seen With Other Treatments

Scientists have suspected for some time that these side effects may be a broader phenomenon of amyloid removal from the brain (see ARF HAI story). In another poster at AAIC, Sperling described the occurrence of vascular edema and microhemorrhages in patients participating in a Phase 2 trial of the γ-secretase inhibitor BMS-708163, developed by Bristol-Myers Squibb (see Drugs in Clinical Trials). ARIA-E was found in three out of 100 patients receiving the drug, compared with zero out of 29 patients receiving placebo. All three were ApoE4 carriers. In one of the three patients, several microhemorrhages were present before treatment started and increased in number and severity during the trial. “This is just three patients, so I don’t want to speculate that this is the same mechanism,” said Sperling. “All I can say is that, at this stage, it looks very similar to the ARIA-E that we detected in patients receiving immunotherapy. No one expected to see this in this γ-secretase inhibitor trial.”

The BMS team itself presented a poster on cerebral microbleeds in a Phase 2 trial of BMS-708163 in people with mild to moderate AD. Led by Howard Feldman, these authors reported that baseline and six-month scans in 175 trial participants revealed the presence of such microbleeds in 26 percent of people, plus, at six months, a 10 percent rate of incident microbleeds in the placebo group, and 13 to 19 percent in the treatment groups. People who had one or more microbleeds at baseline were more likely to have another during the trial, though that did not affect people’s clinical outcome, the scientists reported. This study did not use the new ARIA terminology presented at AAIC.

Preliminary results from ongoing Phase 3 trials of solanezumab, Lilly’s Aβ antibody (see ARF related news story and ARF ICAD story), indicate that “less than 0.5 percent of our patients have vasogenic edema,” said Eric Siemers at Lilly. “We never had seen it in the Phase 1 and 2 studies.” As these trials are ongoing and blinded, Siemers does not yet know which patients with the vasogenic edema belong to the placebo or treatment groups.

Presentations on clinical trials data of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), an old treatment by Baxter Bioscience now being tested for possible use in AD (see ARF related news story and ARF ICAD story), did not provide any information regarding the occurrence of ARIA in IVIG-treated AD patients. However, Lakshman Puli of the University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio, presented data from a Baxter-funded study showing that IVIG does not cause microhemorrhages in a mouse model of AD.

These studies are helping elucidate the mechanisms underlying vascular side effects seen in AD patients, but getting more definitive answers about their clinical impact will have to wait until results of the Phase 3 trials of amyloid-lowering therapies are available. Key questions for bapineuzumab are whether the drug is effective in treating AD and whether its benefits will outweigh side effects. “An extension to these questions is whether any beneficial effect will be greater in patients who have vasogenic edema,” said Gilman. “One possibility is that vasogenic edema is an indication that the drug is removing amyloid-β. Whether or not vasogenic edema has to occur for the antibody to work remains to be determined.”

Another important question is to what extent ARIA-E occurs as part of the natural history of AD. One of the presentations at AAIC by Christopher Carlson from Eli Lilly looked at the prevalence of vasogenic edema and microhemorrhages at baseline—in other words, before patients receive any treatment—in two ongoing multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 3 trials of solanezumab. The study identified two cases of ARIA-E in baseline MRI scans from 2,134 patients. “It seems that ARIA-E rarely occurs spontaneously, and it is probably more likely to occur in people with high vascular amyloid burden,” said Sperling.

New ARIA Guidelines

The talks and posters at AAIC came on the heels of new recommendations by the Alzheimer’s Association working group, published online July 12 in Alzheimer’s & Dementia (Sperling et al., 2011). The recommendations ease some of the safety restrictions the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had previously put in place. “I think that when the FDA first identified the problem, they were correct in establishing strict criteria,” said Andy Satlin at Eisai Inc. in Woodcliff Lake, New Jersey. Satlin has no role in the bapineuzumab trials, but oversees Eisai’s/Bioarctic’s clinical trials for an antibody against protofibrillar forms of Aβ (see ARF related news story). “Then, with the available data, we were able to determine more appropriate criteria that everyone has agreed to.”

The original FDA guidelines directed clinical trial sponsors to exclude participants with more than two existing brain microhemorrhages from studies. But after reviewing all publicly available data, the working group proposed that participants with up to four pre-existing microhemorrhages (or ARIA-H) could enroll in clinical trials. Contrary to what was suggested by a number of news stories that appeared immediately after the working group’s publication, the new guidelines do not change the FDA’s requirements for monitoring patients for ARIA-E. Companies testing amyloid-reducing compounds need to perform frequent MRI tests on patients, typically every three months. Any patient who develops ARIA-E during the trial has to be taken off the medicine until those complications clear, and then treatment can resume. Anyone developing ARIA-H during the trial should continue to receive treatment, provided that these abnormalities do not worsen symptoms. “Microhemorrhages don’t disappear on subsequent MRIs as the edema does, and can be difficult to reliably track over time,” said Sperling, lead author on the working group’s report. “We don’t yet know what ARIA-H occurring in trials means for long-term outcome in AD patients.”—Laura Bonetta.

No Available Further Reading

Last August, Eli Lilly and Company halted Phase 3 clinical trials of semagacestat, its γ-secretase inhibitor, after its Data Safety Monitoring Board discovered that patients on the medication fared worse on cognitive symptoms than those on placebo (see ARF related news story). At the 11th annual Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC, formerly ICAD), held 16-21 July 2011 in Paris, France, Eric Siemers of Lilly told a packed audience what went wrong.

During the first of the 76-week-long Phase 3 trials, which were dubbed IDENTITY and IDENTITY-2, cognitive symptoms of patients in the placebo group increased (or worsened) by 6.2 points on the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive (ADAS-cog) scale, compared to an increase of 7.8 points for patients receiving the highest dose of the drug, said Siemers. He put a positive spin on the findings in pointing out that, so far, other amyloid-β-lowering medications have not budged cognition at all. Semagacestat, on the other hand, “did have an effect,” he said. “It was not the direction we wanted, but it is the only compound that has gone into Phase 3 trials that has had an effect on cognition.”

Lilly promptly halted dosing in the two trials but continued to follow participants for 32 weeks after they received the last dose of the drug. At AAIC, Siemers presented data from the follow-up study of patients in the IDENTITY trial. During the 32-week follow-up, participants' cognition didn't continue getting worse, but neither did it return to baseline or catch up to the placebo group. “The lines did not continue to diverge after dosing stopped, but there was no reversal in worsening,” said Siemers.

The results shed light onto the mechanism of action of the drug. If semagacestat had induced some kind of metabolic change to occur in the brains of people receiving the treatment, which was responsible for the drop in cognition, then removing the drug should have caused the cognition to go back to the same level as in the placebo group. It did not, said Siemers. On the other hand, the fact that the treatment group did not keep getting worse after the trial was stopped means that semagacestat did not set off some kind of pathogenic cascade that continued even in the absence of the drug.

The follow-up results also suggest that reducing the amount of Aβ in the brain is not, in itself, a bad thing, reasoned Siemers. Semagacestat decreases production of Aβ in the central nervous system of patients (see ARF related news story and ARF related news story). This effect, detected during Phase 1 and 2 trials, was thought to bode well for the drug’s success in Phase 3. It is possible that lowering Aβ in the brain isn’t beneficial to patients. Siemers, however, argued that the follow-up data go against that explanation. “The reduction in amyloid is immediate,” he told ARF. “But you don’t see the effects on cognition immediately.” In addition, he said, if removing Aβ was the problem, stopping the drug treatment should cause patients to go back to the same level of cognition as those in the placebo group, which did not happen.

If the semagacestat trial was a downer, Lilly had an upper ready. Any disappointed, travel-weary scientists who were wont to forget about Lilly's AD program could avail themselves of free-flowing cappuccino and, upon taking the first fragrant sip, were promptly reminded whose pleasure it was. Judging by the long lines in the exhibit area, the strategy was a raging success. Image credit: Laura Bonetta

Another explanation is that the negative effects on cognition are due to some other effect of blocking γ-secretase, unrelated to it cleaving the amyloid precursor protein (APP). In addition to targeting APP, γ-secretase regulates the activity of Notch, a protein that is important for cell-to-cell communication in multiple processes and has also been implicated in cancer. But there are additional targets. “When we started the clinical development on semagacestat, the only other known substrate for γ-secretase was Notch,” Siemers told ARF. “Now over 50 substrates are known. If you go through the list of those 50-odd substrates, several imply a plausible story that, if you inhibit γ-secretase, you do bad things.” For example, one substrate, the ephrin type-A receptor 4, is involved in dendritic spine formation.

Aside from cognition, other side effects of the drug seemed to resolve by the end of the follow-up period. Lilly had previously disclosed that 5 percent of trial participants developed squamous or basal cell carcinoma; during the follow-up period, the rate of skin cancer in patients initially treated with semagacestat returned to the rate in placebo-treated patients.

Even though semagacestat failed, Lilly’s approach of using biomarker data to determine that the drug got in the brain in sufficient doses to have the intended biological effect before moving to Phase 3 trials was a valid one, said Siemers. “We have enough biomarker data to say it got in and it hit the target. And we know it did because it is the first compound to go in the brain and change cognition. It did it in the wrong direction, but we think our Phase 2 strategy has potential,” he told ARF.

Others agree. “The semagacestat study was extremely well done. The patients were well selected and followed, they had a good number of patients, they had information about different biomarkers. They did not have a positive result, but we have learned a lot from that trial,” said Joel Menard, who chairs the scientific board that advises the French National Foundation on Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders.

Perhaps the biggest change is that, while the results of AD trials are still negative, recent trials are gradually becoming of better quality than they were in the past decade, when trials failed without the redeeming factor of having taught the field much.

γ-Secretase Inhibition on Trial?

The door is still ajar on γ-secretase inhibitors. The one developed by Bristol-Myers Squibb, BMS-708163, is currently in Phase 2 trials (see ARF related news story and ARF news story). Data presented at AAIC identified a dose range with adequate safety and tolerability, and provided some evidence of γ-secretase engagement and biomarker effects. However, it also hinted that BMS-708163 may end up being more similar to semagacestat than originally anticipated.

Christopher van Dyck of Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, presented data from a recently completed Phase 2 safety and tolerability study in mild to moderate AD. The two lower doses of 25 and 50 mg daily were well tolerated; the two higher doses of 100 and 125 mg daily were not. Importantly, the study also found a trend for cognitive worsening in patients receiving one of the two higher doses, whereas patients receiving the two lower doses showed no significant changes in cognition. None of the patients, regardless of treatment dose, had significant changes in brain volume. However, patients receiving the highest doses showed trends for changes in CSF Aβ concentrations, indicating an effect on the drug’s intended target.

Twice as many patients receiving the two higher doses of the drug elected to discontinue treatment, compared to patients receiving the two lower doses or placebo; the most common reasons for discontinuing were gastrointestinal and dermatological side effects (see ARF related news story). Some patients receiving the drug developed squamous cell carcinoma or basal cell carcinoma, but no cases of melanoma. “The increase in skin cancer bears watching,” said van Dyck. Another ongoing Phase 2 trial of BMS-708163 is testing the 50 mg daily dose against placebo in prodromal AD.

With results on the γ-secretase inhibitor front not looking overly promising, many researchers are hoping for positive results, at least for the group of patients with mild AD, from the Phase 3 results of two antibodies to Aβ: solanezumab by Lilly and bapineuzumab by Pfizer and Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy (a Johnson & Johnson affiliate). Both appear to lower the amounts of Aβ in the brains of AD patients (see ARF related news story and ARF news story on Rinne et al., 2010). If the Phase 3 results, expected in 2012, are negative, then this setback would likely spark intense debate about the validity of the amyloid hypothesis in AD.

No new efficacy data were presented at AAIC on either antibody, but Siemers told ARF of two hopeful signs. When the Data Monitoring Committee looked at the cognitive data for the Phase 3 trial of solanezumab at the analogous snapshot that stopped the semagacestat study, “they recommended that the study continue without modification.” In addition, more than 95 percent of the people who completed the 18-month-long double-blind portion of the Phase 3 trials opted to continue on into the open-label extension trial, compared to less than 80 percent of patients electing to do so for semagacestat.

Bapineuzumab had raised concerns when some patients receiving treatment developed brain swelling and tiny brain hemorrhages (see ARF related news story), but data presented at AAIC suggest that these side effects, now called amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), may be transient and manageable (see ARF related news story).

During this period of waiting, several presentations at AAIC focused on other potential treatments that do not directly target Aβ production or clearance, or that target AD before clinical symptoms develop. Some of those studies, currently ongoing or in the planning stages, are highlighted in Part 2 of this series.—Laura Bonetta.

This is Part 1 of a two-part series on clinical trial news. See also Part 2.

No Available Comments

Updated 03 August 2011.

With the buzz surrounding amyloid-targeting therapies, it is easy to lose sight of the fact that other treatments are being tested as well. Presentations at the 11th annual Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC, formerly ICAD), held 16-21 July 2011 in Paris, France, provided snippets of new information on ongoing trials.

One that is being closely watched is the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study (ADCS) Phase 3 trial of a plasma-derived human antibody product called intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), or Gammagard, developed by Baxter Healthcare. In small studies, this treatment has resulted in both improved cognition and increases in brain volume in AD patients (see ARF related conference story). “As far as I know, the only experimental treatment that has shown a positive correlation between a biomarker and a clinical measure is IVIG,” said Pierre Tariot at the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute in Phoenix, Arizona, who serves as a sub-investigator in the ADCS/Baxter IGIV trial.

It is not yet clear whether IVIG decreases amyloid-β in the brains of AD patients, but the antibody mixture does contain some antibodies against Aβ (Dodel et al., 2011 and Szabo et al., 2010). The drug could have other mechanisms of action, as well, such as immune system-modulating properties, which could explain its beneficial effects. This suggestion came from Norman Relkin at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City in his AAIC presentation. Relkin measured plasma cytokine levels in 24 AD patients who had enrolled in a prior Phase 2 placebo-controlled IVIG clinical trial. Results from that trial indicated that the cognitive symptoms of patients receiving the treatment improved (see ARF related conference story and ARF conference story). In these patients, nine out of 31 blood cytokines tested increased significantly, and in a dose-dependent manner, following IVIG treatment. The nine cytokines were IL-1A, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-13, GCSF, EGF, and VEGF; increases in IL-5 and IL-8 best correlated with six-month cognitive outcomes. Relkin is currently leading the ADCS Phase 3 multicenter trial of IVIG in 390 AD patients. That study is now fully enrolled and expected to read out during the first half of 2013.

AAIC featured a handful of presentations on IVIG. A poster by William Shankle, at the Hoag Neurosciences Institute in Newport Beach, California, reported a slowing of cognitive and functional decline in a subset of 17 patients with AD or Lewy body disease when these patients were treated with IVIG for up to five years. This slowing persisted for up to three years after stopping IVIG in patients who discontinued the treatment. These are not data from a blinded trial; through his private practice in Newport Beach, California, Shankle has for some years administered IVIG to a number of patients, who pay for this treatment out of pocket. “While this is not a controlled, clinical trial, it has the advantage of adjusting each outcome to the patient's own rate of decline before IVIG treatment,” wrote Shankle in an e-mail to ARF.

At AAIC, Anton Porsteinsson of the University of Rochester Medical Center presented some of the data from the Phase 2 trial of ELND005 (aka scyllo-inositol), a potential oral treatment for AD, being developed by Elan Corporation and partner Transition Therapeutics. The drug has been shown to inhibit aggregation of Aβ in transgenic TgCRND8 mice (McLaurin et al., 2006), and based on Phase 2 trial data, the companies announced they would take the compound into Phase 3 (see ARF related news story).

Originally, 353 patients with mild to moderate AD were randomized to one of three doses of ELND005 (250, 1,000, or 2,000 mg), but Elan later dropped the two higher doses because of safety concerns. At AAIC, Elan and academic scientists reported on a poster that there were no deaths in the placebo group versus one death in the 250 mg group and five and four deaths in the two higher dose groups, respectively. Infections also were more common in the high-dose groups. All subsequent functional and biomarker analyses pertain to the lower 250 mg dose.

With regard to function, Stephen Salloway of Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, showed data indicating that the treatment group and the placebo group did not differ significantly on the neuropsychological test battery (NTB) or AD Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living Scale (ADCS-ADL). This means the study missed its co-primary endpoints. The scientists then moved on to subgroup analyses pre-specified in the protocol, and saw that patients with mild AD receiving 250 mg of ELND005 had significantly higher NTB scores at week 78 compared to placebo.

With regard to biomarkers, at week 78, the 84 patients receiving 250 mg of the drug had an increase in their brain ventricular volume compared to the 82 patients on placebo. Ventricular volume expansion indicates atrophy of brain matter. This difference was seen in the subset of patients with moderate AD, not in those with mild AD. Both mild and moderate patients treated with 250 mg of ELND005 also had a 27 percent decrease in CSF amyloid-β 42 (Aβ42) levels after 78 weeks of treatment. CSF total-tau (t-tau) and phosphorylated tau (p-tau) did not change with ELND005 treatment. In toto, then, patients with mild AD showed a positive trend on the study’s primary cognitive outcome and CSF Aβ42 reduction, but no significant change in ventricular volume or CSF t-tau or p-tau, whereas more advanced patients had no cognitive benefit or brain shrinkage.

One of the new kids on the block is PF-04447943, a selective phosphodiesterase-9A (PDE9A) inhibitor that elevates the amount of cyclic GMP in brain and CSF. Pfizer is testing the drug in AD, but as reported in Paris, results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 2 trial were not particularly encouraging. Although the drug was generally safe, Elias Schwam of Pfizer in Groton, Connecticut, explained that after 12 weeks of treatment, there was no significant difference in ADAS-cog scores or in the global clinical scores between 91 patients with mild to moderate AD who received 25 mg of the drug and 100 patients who received placebo. “This suggests that, within mild to moderate, a target like cyclic GMC does not show efficacy in a short trial,” said Schwam. “Maybe the treatment is effective in earlier stages of disease.”

Too Little Too Late

A growing number of researchers are seeing recent failures in AD clinical trials as a sign that treatment is being given too late in the disease process. “We have had some spectacular Phase 3 failures in mild to moderate disease. It is precisely for these failures that we need to move earlier,” said Reisa Sperling of Harvard Medical School. She will be lead investigator for a therapeutic trial of preclinical AD planned by ADCS (see ARF related Webinar).

A proposal for another trial in preclinical AD has also been submitted for funding by the Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative (API) of Banner Alzheimer’s Institute in Phoenix (see ARF conference series), according to a presentation by API’s co-director Pierre Tariot. If approved and funded, that trial should begin by the end of 2012, or, more likely, the beginning of 2013, Tariot told ARF.

In his presentation at AAIC, Tariot reviewed several alternative approaches for designing clinical trials for preclinical AD. He suggested that, in the future, when sufficient data become available to conduct the necessary modeling, Bayesian designs may be well suited to such studies. These permit use of accumulating data analyzed at frequent intervals to decide how to modify aspects of the study as it is being conducted (see ARF related news story). In the meantime, the first trial proposed by API incorporates a so-called adaptive frequentist design with a nested cohort study. The primary outcome of the study would be a change in cognition, but it would also measure different biomarkers. Changes in the biomarkers would be used to make decisions during the trial without prespecifying a hierarchy in response pattern. This information would then serve to design future trials in a different way, as well as to establish the predictive, prognostic, and correlateive value of biomarkers. “Multiple hypotheses can be addressed in this type of trial,” said Tariot.

The trial would be carried out in cognitively normal carriers and non-carriers of mutations causing early onset AD, including a large kindred from Colombia, in which AD is caused by the E280A presenilin-1 (PS1) mutation. Tariot and colleagues have calculated that the trial will probably need to enroll 300 participants without clinical symptoms of AD, including both mutation carriers and non-carriers; carriers would be randomized to treatment. API has proposed a prototype treatment in the grant proposal, although all involved agree that the best available agent will need to be used when such a trial is launched, and the choice could change. Tariot could not, however, disclose the drug the investigators have incorporated in the grant proposal. (see ARF related news story).

“I am really impressed with people wanting to go earlier, as it might be easier to go on to conduct another Phase 3 trial,” said Nick Fox of University College London, U.K., who chaired the session at which Tariot spoke. However, in discussions following the presentation, some conference attendees questioned the rationale of going full-steam with a large trial of preclinical AD before there are officially validated biomarkers or cognitive tests for the condition. Both API and a sister effort for preclinal-stage trials, the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer's Network (DIAN), are doing extensive work on biomarkers and cognition in preparation for clinical trials in their respective populations.

Others question the conclusion that the current failure of AD drugs to succeed in trials of mild to moderate AD means researchers should focus on treating preclinical stages of disease. “People make the argument that, by the time you have AD, you have too much neuronal loss and it is too late. I do not think there are enough data to say that,” said Eric Siemers of Eli Lilly and Company. “The other drugs to date never got into the brain in sufficient quantities to really test the hypothesis. But if you can make the rate of cognitive decline faster [as it happened with semagacestat], you might also make it slower.”—Laura Bonetta.

This is Part 2 of a series on clinical trial news. See also Part 1.

Luc Buée of the University of Lille was one of the few tauists among the plenary speakers at this year’s Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC), held 16-21 July 2011 in Paris. But he did not get a chance to tell the whole story. He was but a few slides away from finishing his talk when he had to step off the stage tout de suite because French President Nicolas Sarkozy was ready to address the audience.

Sarkozy updated a packed hall on the Republic’s National Plan on Alzheimer's and related diseases that his administration implemented for the years 2008 to 2012. "I am very happy that France is hosting, for the first time, the International Conference on Alzheimer’s Disease. We have made the fight against Alzheimer's disease a priority for France since my election in 2007,” said Sarkozy. His 15-minute address featured mots justes that garnered a burst of applause, namely, when Sarkozy announced that his government has pledged €1.6 billion (U.S.$2.3 billion at the time of the conference) to Alzheimer's-related programs over a five-year period. “This is considerable, but I tell you, it’s less costly to give money to researchers and physicians than to wait for the development of the disease,” he said.

French President Nicolas Sarkozy spoke on Wednesday, 20 July 2011, at AAIC. View larger image. Image credit: Alzheimer’s Association

France is one of five European countries that has a dementia plan in place; the other four are Denmark, The Netherlands, Norway, and the United Kingdom (with separate plans for England, Scotland, and Wales). Additional European governments have identified the need for a plan to be developed (for more information, see the Alzheimer Europe website). In January 2011, U.S. President Barack Obama signed into law the National Alzheimer's Project Act (NAPA; see ARF related news story) requiring the creation of a national strategic plan to address the Alzheimer's crisis, but that law to date has no financing attached to it.

The French plan lists 11 objectives and identifies more than 40 comprehensive measures for reaching these objectives, some of which are centered around AD research (for details on the French plan, see the French Alzheimer Plan). Two hundred million euros have been set aside for research, and 70 million of those have already been spent, said Sarkozy at AAIC.

One of the unique features of the French plan is its oversight, said Joel Menard, who helped write portions of the plan. Menard now chairs the scientific board that advises the Fondation Plan Alzheimer, the foundation created to oversee the funding of research under the French plan. “All those involved in heading the various research projects meet around the table once a month to discuss progress, and every six months there is a meeting in the presence of Sarkozy,” explained Menard. “This oversight is to make sure that the money is used correctly and not lost in administration. I guess this is analogous to the U.S. Congress having scientists testify to them once a year,” Menard said.

Currently the Fondation Plan Alzheimer funds more than 100 research projects, said Sarkozy. Projects include the creation of automated image processing algorithms, the long-term monitoring of large patient population cohorts, high-speed genotyping of patients and controls, as well as genome sequencing of the microcebe, a small lemur that develops a disorder comparable to AD. In addition, the French plan has earmarked €5.5 million over five years for doctoral and postdoctoral grants.

Going From SNPs to Function

One of the research initiatives Sarkozy singled out is the European Alzheimer's Disease Initiative (EADI), led by Philippe Amouyel at the Institute Pasteur de Lille and Lille University. (Amouyel also directs the Fondation Plan Alzheimer and was acknowledged during Sarkozy’s speech, along with Menard, Philippe Lagayette, president of the foundation, and Florence Lustman, who has been overseeing the plan on behalf of Sarkozy since February 2008.)

French genomic research has seen a whirlwind of activity in the last two years. In his talk at AAIC, Jean-Charles Lambert, who works with Amouyel at Lille, reviewed EADI’s accomplishments. In 2009, EADI researchers published a two-stage genomewide association study (GWAS) that identified several single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with AD risk, including two loci, CLU/APOJ on chromosome 8 and CR1 on chromosome 1, with genomewide significance (see ARF related ICAD story and ARF related news story on Lambert et al., 2009). Pooling DNA samples from EADI and other consortia that conduct research on AD genetics, Lambert and colleagues subsequently identified BIN1 as a genomewide susceptibility gene (see ARF related news story on Seshadri et al. 2010).

Since then, EADI has formally joined hands with other genomic consortia around the world through the International Genomics of Alzheimer's Project (IGAP; see ARF related news story) to increase statistical power for the discovery of further genetic determinants of AD. IGAP, funded in part by the Fondation Plan Alzheimer, made possible two large GWAS published earlier this year, bringing the total number of AD-susceptibility genes to 10 (see ARF related news story on Naj et al., 2011 and Hollingworth et al., 2011; see top 10 on AlzGene).

EADI researchers are continuing to validate SNPs in larger cohorts and with different statistical methods. For example, a meta-analysis using available data from AlzGene and genotypes from public repositories confirmed that the association of the CR1 SNP rs3818361 to AD risk is highly significant, but its estimated effect size is modest, Lambert said at AAIC. Many polygenic diseases involve several gene variants, each contributing a small portion of the overall disease risk. During his talk, Lambert also presented an emerging approach for characterizing genetic risk factors not detected by classical GWAS. Called genomewide haplotype study (GWHS), this approach uses multi-allelic haplotype markers rather than single-SNP markers in mapping disease loci. Lambert’s group tested more than 37 million associations for each DNA sample to identify a haplotype on chromosome 10p13 that is systematically associated with AD in seven independent European populations comprising 9,938 AD patients and 15,578 controls.

Lambert’s group is further trying to determine how different SNPs might affect the function of genes involved in AD. One approach is to sequence the DNA at a particular locus in hundreds of AD patients, or, as a faster and cheaper alternative, to look for variants in genomes that have already been sequenced through the 1000 Genomes Project (see ARF related news story). Using this approach, Bart Dermaut, a researcher in Lambert’s lab, discovered that many variations at the BIN1 locus, including the most frequently occurring one (SNP105), are in the 5’ region of the gene, suggesting that they might affect BIN1 transcription.

To test the hypothesis, Dermaut and colleagues looked at the expression of BIN1 by immunohistochemistry in the brains of 64 deceased AD patients and 64 people without the disease. They found that BIN1 was expressed at higher levels in AD brains. More specifically, people carrying one copy of the SNP105 expressed 32 percent more BIN1 than controls, whereas people homozygous for the variation expressed 50 percent more. The expression of BIN1 in AD patients further increased according to the Braak stage (see AD clinical guidelines), said Dermaut.

The researchers then turned to the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, as a number of Drosophila AD models are available that overexpress either amyloid-β or tau (see ARF Live Discussion). When the scientists used RNAi to knock down expression of the BIN1 fly ortholog, called Amph, they improved readouts of tau overexpression and toxicity, such as retinal degeneration, notal bristle loss, mushroom body ablation, and neuronal motor performance. On the other hand, BIN1 knockdown did not affect Aβ-related phenotypes, such as the rough eye phenotype. If the results pan out in subsequent analyses, BIN1 “would be the first AD risk factor mechanistically related to the tau pathway,” said Dermaut. For more on French AD science, see Part 2 of this series.—Laura Bonetta.

This is Part 1 of a two-part series. See also Part 2.

No Available Comments

As might be expected, there was a potpourri of French AD science at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC), held 16-21 July 2011 in Paris. One French research initiative par excellence, highlighted in Part 1 of this series, is the European Alzheimer's Disease Initiative (EADI)—but many other efforts also stood out.

EADI genomic studies have relied in part on DNA samples from the prospective Three-City (3C) cohort study (see ARF related news story). This population-based observational study of community-dwelling elderly in the three French cities of Bordeaux, Dijon, and Montpellier has been drawing attention in the U.S. of late for its deep neuropsychology dataset and insight into preclinical AD.

The study has been running for over a decade, and researchers are currently in the process of analyzing the 10-year data. At AAIC, Karen Ritchie at La Colombière Hospital in Montpellier, France, presented four-year follow-up data on risk factors that contribute to the progression from MCI to dementia. The principal factors for men were, in order of significance, ApoE4 allele, stroke, low level of education, loss of Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL), and age. In women, progression most frequently followed IADL loss, ApoE4 allele, low level of education, subclinical depression, use of anticholinergic drugs, and age. These risk factors are consistent with those identified in other population-based studies, said Ritchie. Revised diagnostic criteria for the MCI phase of AD have been recently issued (see MCI Symposium and ARF Webinar).

In another session at AAIC, Jean-Charles Lambert at the Institute Pasteur de Lille mentioned that an analysis based in part on the 3C Study population, led by Dominique Campion of the University of Rouen, gave new insight on the risk for developing AD faced by carriers of the ApoE4 allele. Results showed that people with two copies have a risk of developing AD similar to that women with the BRAC1 mutation have for developing breast cancer (Genin et al., 2011). This result has important implications for disclosing ApoE status to people participating in AD trials, said Lambert (see ARF related news story).

In addition to the 3C Study, the French government is supporting the development of a national network of patients with familial AD, similar to the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN) in the United States (see ARF related news story and ARF news story). The French network consists of a collaboration of 23 memory clinics in Lille, Rouen, and Paris. “The main goal of this network is to improve care for patients with early onset AD, but it also makes biological samples from more than 120 families all over France available for research,” said Joel Menard of Fondation Plan Alzheimer.

Turning the Spotlight on Imaging

Another focus of French AD research under the country’s national plan, said Menard, is neuroimaging. At AAIC, Gaël Chételat at INSERM-EPHE-University of Caen in Basse-Normandie, France, presented research from the French multimodal neuroimaging project on early stage AD, which she heads. IMAP stands for Imagerie Multimodale de la maladie d’Alzheimer à un stade Précoce. The project uses different neuroimaging modalities—such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), functional MRI (fMRI), and positron emission tomography (PET)—to understand the pathological mechanisms that underlie AD.

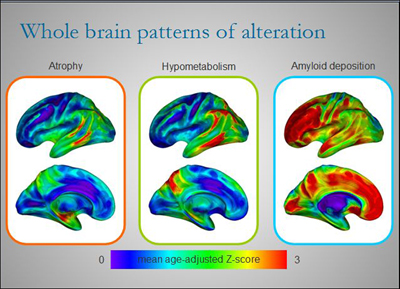

Different regions of the brains of AD patients are affected to varying degrees by atrophy, hypometabolism, and amyloid deposition at any one point in time. Although there is some overlap, each alteration paints its own picture of the disease. By combining several imaging techniques to view AD in patients over time, researchers like Gaël Chételat are starting to build a dynamic picture of disease development and progression. View larger image. Image credit: Inserm U923

These modalities have opened a window into some of the changes that occur in the brains of people as they progress from MCI to AD. PET imaging combined with Pittsburgh Compound-B (PIB), for example, makes it possible to view the increase in Aβ deposition in the brain of patients (see ARF related news story and Hatashita and Yamasaki, 2010). Other changes that occur during this stage include brain atrophy as detected by MRI and a decrease in glucose metabolism as detected by PET combined with the radiotracer 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG-PET) (see ARF related news story). In a plenary session and several posters at AAIC, Chételat and colleagues compared results obtained using these different markers.

In one study, 74 healthy elderly people underwent a PIB-PET scan and two MRI scans 18 months apart to look at differences in amyloid deposition and rate of brain volume change over time, respectively. Chételat and colleagues found that the rate of brain atrophy was higher in people with high Aβ deposition at baseline than in those with low Aβ load, with highest significance in the temporal neocortex and the posterior cingulate cortex. Her findings support the fast-growing notion that Aβ deposition is a pathological condition associated with accelerated neuronal loss. In another study, Chételat and colleagues examined by MRI 61 healthy people aged 19 to 84. They found that the density of the brain’s white matter decreases with increasing age, mainly in the anterior corpus callosum (CC), prefrontal lobe, and posterior CC. This change in white matter parallels the shrinking of the hippocampus, and more specifically of a subpart of this structure, the subiculum, which is the major output area of the hippocampus.

Perhaps the most exciting result from Chételat’s work is that different brain regions are affected by Aβ deposition and other markers of AD to varying degrees at any given point in time. When the researchers looked at three different markers of AD in 16 patients with clinical AD and 26 healthy controls, they found that in most brain areas, the amount of local Aβ deposition exceeded the degree of glucose hypometabolism, which in turn exceeded atrophy. Aβ deposition was highest in the anterior cingulate and prefrontal cortex, where there was little atrophy and hypometabolism, especially in early disease. However, in the hippocampus, the hierarchy was reversed. Here there was a lot of atrophy, whereas hypometabolism was mild and Aβ deposition negligible. Neurofibrillary tangles in early AD were typically confined to the medial temporal lobe and strongly correlated to atrophy in this area.

The regional lack of correlation among the different ways of looking at AD evokes a sense of déjà vu in many scientists. Indeed, the observation has emerged in a piecemeal fashion over many studies and years. It has long puzzled the field, and fueled skepticism of the amyloid hypothesis. As illustrated by the work of Chételat and others, the tools have now been developed for longitudinal multimodal imaging to resolve these earlier findings and reach for le grand prix of understanding brain imaging in AD. That is, establish an integrated, dynamic picture of what changes occur when and where as the brain slides toward AD, and how these changes might be connected, i.e., drive each other, as disease develops.

Moving to the Clinic

Another widely noticed recent French contribution to international AD research has been a new diagnostic framework for prodromal AD recently proposed by the International Working Group for New Research and Criteria for Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease (Dubois et al., 2010 and ARF related Webinar). Researchers hope that the diagnostic guidelines will help them avoid costly faux pas of previous clinical trials.

At AAIC, Bruno Dubois of the Pitié-Salpêtière Hospital in Paris presented results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of donepezil (see ARF related news story), one of the four FDA-approved drugs available for treating AD symptoms, in a carefully selected population.

A total of 216 patients with early AD were randomized to receive 10 mg daily of donepezil or placebo. These patients did not have dementia, i.e., would not have met the old 1984 diagnostic criteria for AD, but had increased amyloid deposition in their brains as indicated by PET scans. Researchers obtained automated reading of hippocampus size using a new software developed by Marie Chupin at the University of Paris. The results showed that patients in the donepezil group had a 45 percent lower rate of hippocampal atrophy than those in the placebo group after one year. There was no difference between groups on any of the cognitive measures included in the study.

Dubois said they were able to see such a striking effect on hippocampal volume with this drug because they selected the right population, otherwise the effect would have been diluted. “The study is exciting for two reasons. It shows a dramatic effect of a drug [on a biomarker], and it validates the selection criteria for prodromal AD,” Dubois told ARF. “The clinical trial was conducted entirely in France,” he added. MRI is being discussed internationally as an outcome measure for earlier-stage clinical trials.—Laura Bonetta.

This is Part 2 of a two-part series. See also Part 1.

No Available Comments

July 18, 2011. Alzforum has covered the connection between traumatic brain injuries (TBI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in a recent series (see ARF related news story). Two presentations at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC, formerly ICAD) bolster that link. AAIC was held 16-21 July 2011 in Paris, France.

Severe brain injuries, such as traumatic brain injuries (TBI), have been shown to induce deposition of amyloid-β peptide and increase the risk of AD. How milder concussions, occurring repeatedly over time, might also lead to dementia is less clear. Some studies have shown that athletes who suffer repeated concussions develop a form of brain degeneration, different from AD, known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) (e.g., see ARF Live Discussion and ARF related news story). “Determining the prevalence of the two conditions and developing clinical and biomarkers for distinguishing the two are high priorities,” wrote Sam Gandy of the Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City in an e-mail to ARF.

But not everyone agrees that the two types of injuries lead to dementia via distinct mechanisms. “I don’t subscribe to the theory that repetitive head trauma results in some clinical entity that is completely different from Alzheimer’s disease,” said Christopher Randolph of Loyola University Medical Center in Chicago, Illinois. Instead, Randolph believes that repeated concussions from many years of playing contact sports may result in diminishing brain reserve—essentially making the brain less able to withstand damage as it accumulates throughout a person’s life. As a result, neurodegenerative diseases such as mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD occur at an earlier age than they normally would.

At AAIC, Randolph presented preliminary data to support his conclusion. In 2001, Randolph and colleagues had mailed a general health survey to more than 3,000 retired NFL players. All players over 50 who responded to that survey then received an additional survey in 2008. The second survey specifically focused on memory issues, including an Alzheimer’s screening questionnaire known as the AD8. The brainchild of James Galvin, now at New York University in New York City, the AD8 has been validated against the clinical dementia rating scale and against neuropsychological tests (see ARF Live Discussion).

In total, 513 people completed the follow-up surveys, including the AD8, which had to be taken by both the former player and his spouse. Just over 35 percent of respondents had an AD8 score of 2 or higher, which suggested possible dementia. “It is a remarkably high proportion of people with cognitive impairment,” said Randolph. “The average age of people who completed the surveys was 61, which is fairly young.”

Former players thought to have cognitive impairment were interviewed by telephone, and then 41 of them came in for neuropsychological testing. The tests included the Repeatable Battery for Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) and a short form of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-II. Their results were compared to those obtained by examining two groups of non-athletes: 41 demographically similar adults with no cognitive changes and a clinical sample of 81 people diagnosed with MCI.

These numbers are small. That said, the athletes showed definite signs of being impaired when compared to the demographically similar adults. In addition, their MCI was similar to that of other adults with MCI, except the athletes were slightly less impaired. “Our suspicion is that former athletes have higher rates of cognitive impairment than do non-athletes, and that their type of cognitive impairment looks very much like prodromal AD,” said Randolph. “However, we will need a larger prospective study to confirm this result.”

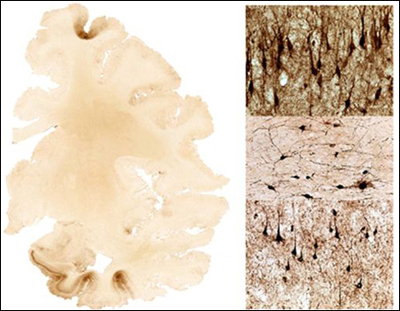

But not everyone is sold on the conclusion. “They propose that these former athletes have MCI, but our experience is that it is more likely to be CTE,” said Christopher Nowinski at the Boston University School of Medicine. “Right now, we don’t have any way to distinguish the two clinically.” Both AD and CTE can lead to dementia, but on pathological examination, AD brains show the presence of amyloid-β deposits, whereas CTE brains show more signs of tauopathy (see McKee et al., 2009).

Brain section from a person with repeated traumatic brain injuries shows dense tau deposits in frontal cortex and medial temporal lobe (dark brown areas). The panels on the right show tau-positive neurofibrillary tangles and abnormal neurites. View larger image. Image credit: Ann McKee

The mechanistic link between TBI and AD is more established. However, it is not clear how prevalent TBI is, and to what degree it increases AD and dementia risk. “A particular challenge in determining the prevalence is the latency between injury and clinical manifestations,” said Gandy.

To help address such questions, Kristine Yaffe at the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues reviewed medical records of 281,540 U.S. veterans age 55 years and older who received care through the Veterans Health Administration. These people had had at least one inpatient or outpatient visit at some point in 1997-2000 (baseline period) and a follow-up visit in 2001–2007.

Yaffe and colleagues searched the database for people with a TBI diagnosis, including intracranial injury, concussion, skull fracture, and unspecified head injury. They then determined whether TBI of any type was associated with a greater risk of being diagnosed with dementia at the follow-up visit. The results, which were presented at AAIC, indicated that about 2 percent of older veterans had a TBI diagnosis during the baseline period. The risk of developing dementia was 15.3 percent for people with a TBI diagnosis compared with 6.8 for those without (p The results build on earlier findings from other groups (Plassman et al., 2000). What is new here is that “this is the largest study to date with almost 300,000 participants. We were able to look at mild TBI and subtypes of TBI, and the follow-up was seven years,” wrote Yaffe in an e-mail to ARF. “We also carefully adjusted for other variables, such as medical and psychiatric comorbidities.”

“The large sample size yielding very tight confidence intervals makes this an impressive effort,” wrote David Brody at Washington University in St. Louis in an e-mail to ARF. “Imaging and other biomarker-based assessments of an epidemiologically valid subset of the subjects would be a logical next step.”—Laura Bonetta.

No Available Comments

In the fall of 2009, a large quality control (QC) program started comparing measurements of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers from labs across the world (see ARF related news story). The aim was to come up with standard procedures that would ensure consistent results. Two years later, the initiative’s main accomplishment has been to recruit more than 60 labs to participate in the project, but consistency across labs remains elusive, according to presentations at the 11th annual Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC, formerly ICAD) held 16-21 July 2011, in Paris, France.

Achieving consistency across labs has emerged as a key challenge in the field, which in the past two decades has amassed strong evidence that CSF markers can predict AD. Consistency is necessary if this evidence is ever to be applied to multicenter treatment trials, and especially in broad clinical settings beyond a few leading academic medical centers. Brain imaging faces its own standardization challenges. Compared to CSF biochemistry, this field is at an even earlier stage in that regard, as large-scale standardization initiatives are only just beginning to form.

Three times a year, the Alzheimer’s Association Cerebrospinal Fluid Quality Control Program, headquartered at the Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Molndal, near Göteborg, Sweden, sends out for testing three CSF samples to each of the participating labs. Two of the samples are unique to each round of testing, and serve to gauge the variability in measurements among labs; the third sample is the same every time to assess longitudinal stability of measurements. At the same time, four reference laboratories process several additional copies of every CSF sample to determine the variability in measurements within a single lab (see ARF related news story). The samples are analyzed for the presence of the three most established biomarkers: amyloid-β42 (Aβ42), total-tau (t-tau) and phosphorylated tau (p-tau).

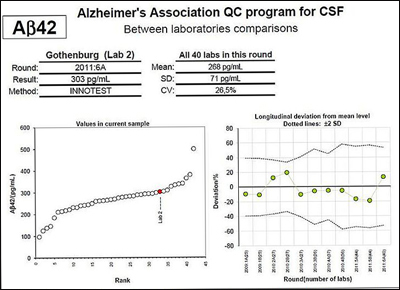

At AAIC, Kaj Blennow at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, who heads the QC program, presented the results of the first six rounds of testing (Mattsson et al., 2011). He showed scatter plot graphs of biomarker measurements, indicating variation among laboratories in the range of 13 to 36 percent. Variation of less than 5 to 10 percent is the goal. “You can see quite marked drift among labs,” said Blennow.

Variation was similar irrespective of the assay kit used for the test (i.e., INNOTEST ELISAs, Luminex xMAP or MSD). Furthermore, the group did not see differences in variability among rounds of testing, in other words, variability is not yet going down with repeat testing. “Variability for tau is a bit less than for Aβ42 but still higher than we need,” said Blennow’s colleague Henrik Zetterberg, also at the Sahlgrenska University Hospital.

The left panel shows results from all labs doing the INNOTEST amyloid-β42 (Aβ42) ELISA on one of the unique CSF samples sent to them, with one lab indicated in color. The panel on the right shows the percent deviation in measurements obtained by the same lab for the longitudinal sample over six rounds of testing (two measurements performed for each round). Both panels show marked variation. Although some of the reference labs that are part of the QC initiative are able to obtain reproducible results time after time, most participating laboratories do not yet produce consistent results. View larger image. Image credit: Kaj Blennow

But despite this seeming lack of progress, Zetterberg said there is reason to be optimistic. “The reference laboratories that are part of the initiative are collecting longitudinal data, and those labs do produce stringent results that are reproducible time after time, except that we sometimes see changes due to batch variation among kit lots,” he said. “This means that standardization across labs should also be possible.”

There are many possible sources of variation in measuring CSF biomarkers, which have been previously discussed on Alzforum (see ARF related news story). In order to pinpoint the main ones and eliminate them from future rounds of testing, the Sahlgrenska group has started asking participating labs to fill out a checklist for each analytical technique. The checklists include information on assay reagents and instruments, details on sample handling and storage, such as which kinds of pipette tips or plates the technician used, as well as questions about internal control samples, assay conditions, settings for data analysis, and so on. They will be available on the program’s website.

The QC program has already developed standardized protocols for participating labs to follow when measuring CSF biomarkers, but they are “not detailed enough,” Zetterberg told ARF. “We are collecting more detailed information and in the long-run will be able to reduce variability.” The group will conduct hands-on practical courses to train lab personnel on how to carry out the standardized protocols (see ARF related news story).

Moreover, the program is pushing for better assay kits on the market. “Biomarkers in other fields of medicine (i.e., troponin-T and cholesterol) have gone through similar standardization procedures, and biotech companies producing this type of assay have put in the time, effort, and money it takes to make highly validated tests. We hope that the same will come true for these AD CSF biomarkers,” wrote Blennow in an e-mail to ARF.

Zetterberg stressed that the observed variability in CSF biomarkers measurements among labs does not diminish the value of these markers in research. “A lab that has established rigorous methods of its own can reliably monitor relative changes in biomarkers,” he said. As an example, at AAIC, Zetterberg presented a study showing that relative changes in biomarker levels can be used to predict with high certainty which patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) will go on to develop AD. His group measured CSF biomarker levels in 137 people with MCI at the start of the study and then followed these people clinically for more than nine years. Previous studies have reported that CSF markers predict AD risk at the MCI stage, but not with follow-up that long. During those nine years, 54 percent developed Alzheimer’s, and those people who did had had lower CSF Aβ42 levels and higher t-tau and p-tau when compared to people who did not. “Aβ is already down nine to 10 years before progression to AD,” said Zetterberg. The ratio of baseline Aβ42/p-tau predicted the development of AD within 9.2 years with a sensitivity of 88 percent and specificity of 90 percent.

Eventually, researchers would like to have biomarkers that determine whether someone who has no clinical symptoms of MCI is at risk for developing AD—somewhat akin to taking a cholesterol measurement to ascertain one’s risk for cardiovascular disease. At AAIC, Zetterberg said his group just completed a study of 86 healthy people who were followed for 13 years. Fourteen of them developed AD during this time. Preliminary data from his lab indicate that those individuals with CSF Aβ42 levels lower than 700 pg/mL are at higher risk for developing AD. “But I do not advocate screening at this stage,” said Zetterberg. “These data are purely for research purposes.”

In future, if researchers do find reliable CSF biomarkers for preclinical AD, having consistent results across labs will be essential to instituting universal cutoff levels that can be used to determine risk or establish a diagnosis. Standardization will also be necessary for comparing results of studies from different labs.

Think Standardizing CSF Is Hard? Try Hippocampal MRI

In the wake of the CSF Quality Control Program, other initiatives are springing up to make diagnostic markers for the early detection of AD robust across centers. Giovanni Frisoni of the San Giovanni di Dio Fatebenefratelli Hospital in Brescia, Italy, and Clifford Jack of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, are heading an initiative formally named A Harmonized Protocol for Hippocampal Volumetry: An EADC-ADNI Effort. (EADC stands for the European Alzheimer’s Disease Consortium, and ADNI is the U.S.-based Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative).

Hippocampal volumetry has proved its value in aiding AD diagnosis and in tracking disease progression (see ARF related news story on Erickson et al., 2011). Before it can move into wider clinical use “we have to agree precisely on what to measure,” said Frisoni. “Measurements must be standardized so that they can be used in all memory clinics all over the world.”

As a first step in this process, Frisoni’s group surveyed all published protocols for assessing hippocampal volume. “If you look at the hundreds of publications on the subjects, you'll find tens of different ways of segmenting the hippocampus. Of these, 12 are the most popular among scientists,” said Frisoni. Segmentation is the way outlines of brain structures are drawn on magnetic resonance images to delineate those structures; using different segmentation techniques leads to different estimates of hippocampal volume.

Frisoni’s group took the 12 most popular protocols and evaluated the information each one provides and its reliability in measuring AD-atrophy. These data were then fed to an international task force of experts who were asked to harmonize currently used segmentation protocols and come up with a single standard procedure for everyone to use. The task force comprises principal investigators at EADC and ADNI centers as well as other imaging centers across the world, comprising more than 30 groups in all.

The task force is currently developing and testing the harmonized protocol. Once it has been defined in minute detail, researchers at different imaging labs participating in this effort will have a chance to compare it to the segmentation procedures they currently use. Following this validation step, Frisoni and Jack plan to create a Web portal for people to obtain certification as an expert Qualified Hippocampal Tracer, wrote Frisoni in an e-mail to ARF. Tracers are people in imaging labs with expertise in brain anatomy; for the certification, they will need to manually trace the boundaries of the hippocampus slice by slice on a high-resolution computer screen. In addition, the group plans to develop educational material on how to use the harmonized protocol and hippocampal probability maps that will provide a reference for the tracings.

The finalized guidelines should be made available to the research community in September 2012, said Frisoni. Once available, they will be open to discussion and validation. More information and updates on the program can be found on the EADC-ADNI Initiative website.—Laura Bonetta.

No Available Comments

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.