Zuers—Can Spatial Navigation Guide Clinical Trials?

Quick Links

Like many Alzheimer’s disease research conferences these days, the 8th International Winter Conference on Alzheimer’s Disease, held 7-10 December 2012 in Zuers, Austria, hosted ample discussion of how a field lost in the rubble of negative trials can find its way out. As part of that conversation, it featured a little-known proposal. What if prodromal AD patients could be tested before and after treatment in a human version of the Morris water maze? After all, this mainstay of spatial navigation testing worked for tarenflurbil, bapineuzumab, and other drugs whose promising mouse effects withered when measured by the ADAS-cog in Phase 3. No one is suggesting nudging AD patients into a pool. Instead, Jakub Hort of Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic, and John Harrison at Metis Cognition in Kilmington, U,K., are pitching a real-life, dry version of the Morris water maze in hopes that the AD field will explore whether this kind of testing might be useful in trials. If so, most prospective patients may end up "navigating" a computerized version.

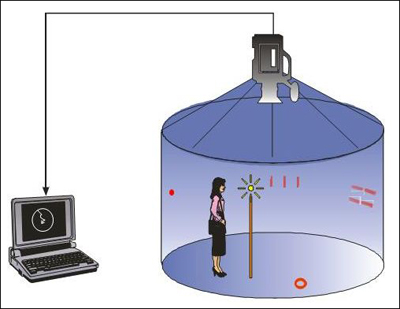

Human water maze for testing spatial navigation in prodromal Alzheimer's disease. Image courtesy of Jakub Hort

The scientists’ argument goes like this: One reason why preclinical data have failed to translate to patients may be that different phases of drug development tap different cognitive domains. At the mouse stage, it is spatial navigation; in humans, it is primarily episodic memory with verbal or visual tasks. “After all, mice don’t speak and AD patients don’t swim,” said Hort. The Morris water maze is as entrenched in mouse treatment studies as is the ADAS-cog in late-stage AD trials, said Harrison. “It is there; you have to work with it.” The disconnect can’t easily be bridged by going backwards from humans, as mice won’t start remembering word lists any time soon. However, Hort thought that forward continuity from preclinical through Phase 3 could be achieved by testing spatial memory in humans. It is something people use every day. “A test for finding your way across space will be more valid across cultures than the paper-and-pencil tests that were originally developed for white Anglo-Saxon college students,” Harrison quipped.

The new spatial navigation measure, Hort believes, could identify people with prodromal AD and detect drug response in clinical trials in this sought-after population. His is not the first attempt to provide much-needed predictive validity to the Morris water maze. The eight-arm spatial memory task of the CANTAB was developed with the same intention. Alas, its execution did not measure up to the idea, and it never found wide application in AD clinical trials, said Harrison. “There are no studies that show it is predictive clinically of what you have seen preclinically,” he said.

The Blue Velvet Arena

Hort developed a human analogue of the water maze, in which the person enters a circular tent 2.9 meters wide, enveloped by a dark-blue velvet curtain. Called Blue Velvet Arena, the installation’s name is eerily similar to Blue Velvet, a popular 1986 motion picture by David Lynch about a creepy, sinister world most people would not care to enter. According to the website of Polyhymnia TS, a company that classics aficionado Harrison founded with Hort and Manfred Windisch, the tent’s new name is Urania, after the daughter of Zeus and Mnemosyne. Readers who remember their Greek mythology may have already guessed that the computerized version goes by the name of Clio, Urania’s sister.

Inside, the arena features navigation signposts projected onto the curtains along its perimeter which guide volunteers in their task of locating a target. This exercise distinguishes allocentric navigation, which is independent of the seekers' starting position and uses the hippocampus and vision, from egocentric navigation, which incorporates people’s starting position and taxes primarily their parietal cortex and proprioception. Of the two, allocentric navigation is the kind that declines more at the prodromal stage of typical AD.

Initial performance data on cognitively normal volunteers and people with amnestic MCI and AD were published five years ago (see ARF related news story on Hort et al., 2007). Since then, follow-up papers have expanded the finding. One characterized the measured cognitive impairment (Laczó et al., 2009), one reported that ApoE4 status worsened spatial navigation in the arena (Laczó et al., 2010), and one linked allocentric navigation in prodromal AD to right hippocampal volume (Nedelska et al., 2012). This latest paper also reports data on how well a 2-D computer version, which would be cheaper to install in clinical sites than a physical arena, corresponds to the real-space test. For a review on spatial navigation in AD, see Gazova et al., 2012).

Hort noted in Zuers that he will soon publish data on 200 patients that suggests spatial navigation is a separate cognitive entity. Data on memory, language, executive, and visuospatial functions do not fully explain the variance he measures. “We think spatial navigation is a promising cognitive domain. We would like to evaluate our test in the context of clinical trials,” Hort said.

As a first step toward knowing whether the test responds to drug treatment, Hort reported on two small trials, one with donepezil in mild AD, one with scopolamine in healthy volunteers. When 18 newly diagnosed patients with mild AD started taking donepezil, their egocentric navigation stayed unchanged but their allocentric navigation improved slightly after three months, along with a small improvement on standard tests of delayed recall. The scopolamine trial—a crossover design in which each volunteer was subjected to each intervention at some point—disrupted their navigation at several hourly time points after they received a single dose of scopolamine; donepezil partially reversed this deficit.

The first paper in a major journal on the human Morris water maze came out in PNAS in 2007, but thus far, AD researchers have not adopted it. Why not? The research is sound, according to John Growdon at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, who called it an innovative approach to neuropsychology. “I have no qualms about the quality of the science; in fact, I am a proponent of this. To have a cognitive test in humans that mimics that in animal models is clearly an advantage for drug discovery,” said Growdon, who had intended to try out the virtual version at MGH until a grant application to this effect went unfunded.

A sometimes contentious bunch, neuropsychologists tend to hold strong beliefs in their own tests—or their favorite tests. It can take a while for a newbie to break in. Hort is known to the Alzheimer’s research community; for example, he co-organized the 2009 AD/PD Conference in Prague. The test might gain prominence if Hort made it readily available to a dozen or so leading neuropsychologists in the U.S. and Europe, inviting them to validate it with their local patients and comparing it to other tests they use for the prodromal/MCI stage. “That would be the U.S. style of gaining acceptance within the research community. It worked very well when the transgenic mice came out, for example,” said Growdon. This kind of outreach early on can persuade leaders in the field that the first published reports on a new test are true and robust. Hort and Harrison are licensing academic use of the technology to other interested research teams.

Commercialization may be a consideration in researchers’ minds as well. In the United States, there is movement away from fee- or license-based tests; for example, the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) is substituting some proprietary tests for free alternatives, even though the former have been used in observational research (see ARF related news story). “The fees can be an irritant and make consortia move away from such tests, even if that undercuts the longitudinal aspect of some studies,” said Growdon.

In Zuers, the audience urged Hort to compare the human Morris water maze directly to the ADAS-cog. “Head-to-head comparison has not been the primary objective of the ongoing research yet. This will be the next step. Our priority so far has been to translate animal spatial navigation data to clinical practice,” Hort wrote to Alzforum.

So far, one Blue Velvet Arena exists at the University of Prague, and similar installations exist in Kiel, Germany, and Warsaw, Poland, Hort said. One is being built at the research offices in Graz, Austria, of JSW, the CRO founded by Polyhymnia partner Windisch. Clinical trials within the catchment area of those cities could use these installations. “The limit for wider dissemination of the real-space version lies in its complexity, cost, and need for an experienced staff,” Hort wrote.

The computerized test could become more widely applied. Its correlation with the real thing is not perfect, the scientists agreed. At present it explains about 64 percent of the results in the real-space version, Hort wrote. “I suspect that ultimately we will be asked to show proof of concept using the Blue Velvet Arena, and that the computerized version will be employed in later confirmatory studies,” Harrison wrote to Alzforum.—Gabrielle Strobel.

This concludes a four-part conference series. See also Part 1, Part 2, Part 3. Read a PDF of the entire series.

References

News Citations

- “Morris Land Maze” Reveals Early Loss of Spatial Memory in MCI

- Zuers—Meeting Mixes Translational News and Debate

- Zuers—Αlpha, Beta, Sigma: Which Will Yield New AD Drug?

- Zuers—No Pill or Drip: Scientists Inject Phage Drug Into CSF

Paper Citations

- Hort J, Laczó J, Vyhnálek M, Bojar M, Bures J, Vlcek K. Spatial navigation deficit in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Mar 6;104(10):4042-7. PubMed.

- Laczó J, Vlcek K, Vyhnálek M, Vajnerová O, Ort M, Holmerová I, Tolar M, Andel R, Bojar M, Hort J. Spatial navigation testing discriminates two types of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Behav Brain Res. 2009 Sep 14;202(2):252-9. PubMed.

- Laczó J, Andel R, Vyhnalek M, Vlcek K, Magerova H, Varjassyova A, Tolar M, Hort J. Human analogue of the morris water maze for testing subjects at risk of Alzheimer's disease. Neurodegener Dis. 2010;7(1-3):148-52. PubMed.

- Nedelska Z, Andel R, Laczó J, Vlcek K, Horinek D, Lisy J, Sheardova K, Bures J, Hort J. Spatial navigation impairment is proportional to right hippocampal volume. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 Feb 14;109(7):2590-4. PubMed.

- Gazova I, Vlcek K, Laczó J, Nedelska Z, Hyncicova E, Mokrisova I, Sheardova K, Hort J. Spatial navigation-a unique window into physiological and pathological aging. Front Aging Neurosci. 2012;4:16. PubMed.

Other Citations

External Citations

Further Reading

Papers

- Kalová E, Vlcek K, Jarolímová E, Bures J. Allothetic orientation and sequential ordering of places is impaired in early stages of Alzheimer's disease: corresponding results in real space tests and computer tests. Behav Brain Res. 2005 Apr 30;159(2):175-86. PubMed.

- Deipolyi AR, Fang S, Palop JJ, Yu GQ, Wang X, Mucke L. Altered navigational strategy use and visuospatial deficits in hAPP transgenic mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2008 Feb;29(2):253-66. PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

Metis Cognition Ltd.

Regarding the call for comparative ADAS-cog data, the donepezil data that was shown in Zuers neared significance with a quite small cohort, which suggests greater sensitivity than the ADAS-cog. The ADAS-cog typically requires N = 200 per arm over six months to show efficacy. I would be surprised if the correlation turns out to be less than 0.7. It will probably be higher, as both measures fundamentally measure memory, though with different degrees of sensitivity.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.