Brain of Woman Who Died on Leqembi Shows Worst-Case Scenario

Quick Links

Part 2 of 2. Click here for Part 1.

What happens in the brain of a person with fatal ARIA? Researchers now have one of their first detailed looks at the pathology of this rare and calamitous condition. In the December 12 Nature Communications, researchers led by Matthew Schrag at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, published postmortem data from a woman who received three doses of the anti-amyloid antibody lecanemab in the open-label extension of the Phase 3 Clarity study. The autopsy showed extensive vascular inflammation and numerous ruptured blood vessels that led to bleeding throughout her brain. She likely died of complications from lecanemab treatment, the authors concluded.

- The second neuropathological study of active ARIA, like the first, finds vascular inflammation throughout the brain.

- The condition resembles inflammation related to cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

- Aβ-immune complexes trigger perivascular macrophages to damage vessels.

Costantino Iadecola at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, said the inflammatory findings resemble those seen in trials of earlier immunotherapies, such as bapineuzumab and the active vaccine AN-1792. He suggested that the term ARIA, i.e., amyloid-related imaging abnormalities, is a misnomer for what is actually Aβ-related vascular inflammation. “The emerging picture is of an innate immune attack on blood vessels, triggered by Aβ,” he told Alzforum.

Why did treatment go so badly for this woman? Schrag and colleagues found she had previously unrecognized risk factors that made her a poor candidate for immunotherapy, being an APOE4 homozygote with severe cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

Several experts told Alzforum the presence of CAA is the critical factor sparking ARIA. “The data … support the hypothesis that the mechanism underlying ARIA closely relates to CAA and likely shares many mechanistic links with CAA-related inflammation,” Mariel Kozberg at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, wrote to Alzforum (full comment below).

Researchers Alzforum spoke with emphasized that to avoid future deaths and other serious outcomes, clinicians will need to screen potential immunotherapy patients carefully, looking in particular for signs of CAA. With thousands of people nationwide now being treated with lecanemab for early Alzheimer’s disease, clinicians must quickly learn to do this well (see related story).

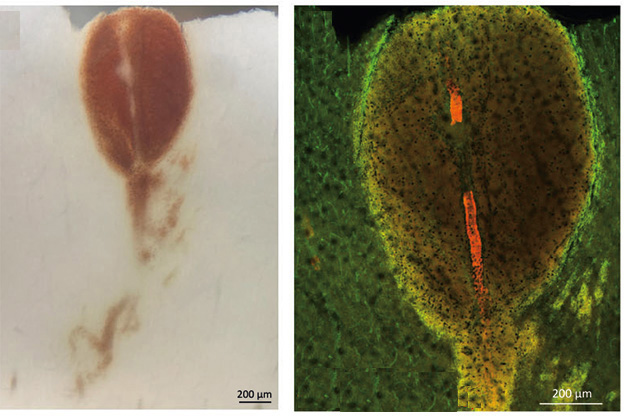

Bursting Pipes. In a woman who died from ARIA after lecanemab treatment, blood vessels (green) in the meninges were packed with amyloid (red) and bulging with multiple aneurysms (arrows, inset). [Courtesy of Solopova et al., Nature Communications.]

Catastrophic Vascular Breakdown

Previous autopsy data have been sparse, but a few cases from the AN-1792 and bapineuzumab trials had already shown that amyloid immunotherapy can worsen CAA. This is believed to happen because Aβ freed from plaques drains into the basement membrane around blood vessels and gets stuck there. These clogs are associated with inflammation and vascular damage (Roher et al., 2011; Roher et al., 2013; Sakai et al., 2014). Nonetheless, this inflammation had not been directly linked to ARIA, which was first defined in conjunction with the bapineuzumab trials (Jul 2011 conference news). Autopsies of people taking bapineuzumab were done long after their ARIA had resolved.

More recently, three deaths in the Clarity OLE were blamed on ARIA, raising fresh concerns (Jan 2023 news). An autopsy report from one of those deaths, a 65-year-old woman who suffered an ischemic stroke while on lecanemab and received the clot-busting drug tPA in the emergency room, showed massive cerebral bleeding as the cause of death. She was also an APOE4 homozygote with CAA. Her large number of hemorrhages would be unlikely to be caused by tPA and CAA alone, the pathologists concluded (Reish et al., 2023; Castellani et al., 2023).

The new paper describes the pathology of another one of the OLE deaths, a 79-year-old woman in Florida who had been on placebo in the Clarity trial. Transitioned to lecanemab in the OLE, after each dose she experienced severe headaches that required a day or two in bed to recover. After the third dose, she became confused, and said she had “brain fog.” She started seizing, was taken to the hospital, and died five days later.

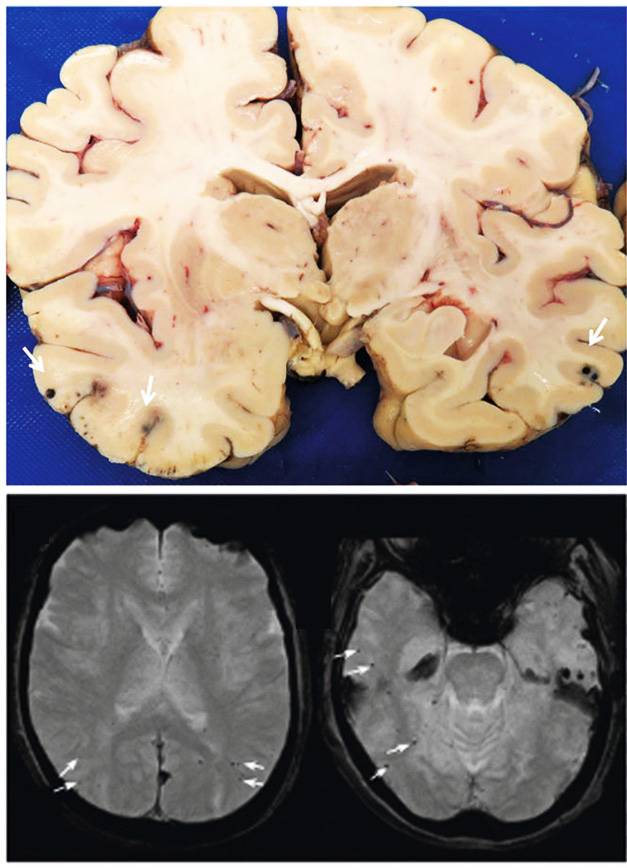

Black Dots. Pathologists counted more than 30 microhemorrhages (arrows) scattered throughout the brain of a woman who died with ARIA (left). Not all of them showed up on MRI (right). [Courtesy of Solopova et al., Nature Communications.]

Joint first authors Elena Solopova and Wilber Romero-Fernandez, both at Vanderbilt, compared her MRI at the time of death to her baseline MRI before the start of OLE. At baseline, four microhemorrhages were visible, just below the cutoff for treatment with lecanemab. Significantly, however, her baseline MRI met the criteria for probable CAA, the authors noted. CAA was not an exclusion criteria in the Clarity trial. Emerging evidence suggests severe CAA should contraindicate amyloid immunotherapy (Aug 2023 conference news; Aug 2023 conference news).

After lecanemab treatment, edema was evident throughout her temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes, and more than 30 microhemorrhages were scattered across these areas. As expected, the autopsy identified even more ruptured vessels that the MRI had missed (see image above). Routine clinical MRIs are lower-resolution than postmortem examination.

“The amount of white-matter lesions was surprising to me,” Iadecola noted. “They blossomed all over her brain. Cases like this highlight how badly things can go.”

Rupture and Spill. Blood leaks from a split in a vessel wall (left). On right, same vessel is shown with amyloid deposits (red), the gap where it ruptured, and diffuse leakage (yellow). Vessels stained with isolectin (green). [Courtesy of Solopova et al., Nature Communications.]

Similar to the previous case reports, the Florida woman’s cerebral blood vessels were inflamed. Where there was edema, numerous activated macrophages and T cells crowded around arterioles in the parenchyma. Some of the macrophages were multinucleated giant cells, which usually form when several immune cells fuse in response to infection. Vessel walls were degenerating, their dying cells interspersed with antibody-Aβ complexes and deposits of fibrin. This is called fibroid necrosis. In the leptomeninges as well, the authors found leaking vessels packed with CAA and surrounded by activated macrophages and microglia.

The overall findings resembled CAA-related inflammation, the authors said. They noted that the neuropathology matched that of the previous APOE4 homozygote case described in Castellani et al. “These two cases are the only detailed neuropathological descriptions of active ARIA in the existing literature,” Solopova and colleagues wrote.

Time to Retire the Term “ARIA”?

Iadecola considers these neuropathological data indispensable for piecing together the puzzle of ARIA mechanisms, especially because there are no good animal models for the condition. He thinks the findings suggest that either Aβ or Aβ-antibody complexes around blood vessels trigger perivascular macrophages to spew cytokines and free radicals, which damage the vessels, causing them to spring leaks.

Other researchers believe excess Aβ itself is the trigger. “The findings offer support for the hypothesis that following immunotherapy against Aβ, the solubilized Aβ from plaques becomes entrapped in the pathways for intramural periarterial drainage,” said Roxana Carare at the University of Southampton, U.K. When those drainage pathways are compromised, for example in someone with cerebrovascular damage, the person is unable to clear Aβ, and ARIA develops, she wrote (full comment below).

Meanwhile, recent work from Eli Lilly places more blame on antibody complexes than Aβ alone. In mouse models, they found that antibodies interacted with vascular amyloid to activate perivascular macrophages (Taylor et al., 2023). “These findings again suggest the importance of perivascular macrophages in the vascular inflammation associated with ARIA,” Kozberg noted.

Iadecola also points an accusing finger at these cells. “Leptomeningeal and perivascular macrophages are really what’s causing the problem,” he told Alzforum.

As it is dawning on researchers what ARIA really is, some researchers think the term may have outlived its usefulness. “It’s no longer an ‘imaging abnormality,’” Iadecola said. Fabrizio Piazza of the University of Milano-Bicocca, Italy, believes it should be called iatrogenic CAA-related inflammation. “ARIA-E is the imaging manifestation of the complex (auto)immune biological mechanisms of CAA-ri,” he wrote (comment below).

How To Avoid ARIA?

It’s stating the obvious that prescribers want screening protocols for amyloid immunotherapy that are keenly sensitive to preventing such outcomes in the future. One approach could be to set a lower cutoff for microhemorrhages, which often indicate the presence of CAA. Solopova and colleagues wrote in their paper’s discussion that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration had initially suggested excluding anyone with two or more microhemorrhages from participating in amyloid immunotherapy trials. Early on, a working group convened by the Alzheimer’s Association recommended the current standard of four (Sperling et al., 2011; Schindler and Carrillo, 2011).

Recent data from Steven Greenberg at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, hint that a lower number could improve safety. Analyzing data from donanemab trials, he found that the presence of two or more microhemorrhages at baseline doubled a person’s odds of developing ARIA-E during the trial (Nov 2023 conference news).

For their part, Solopova and colleagues recommended standardizing the MRI protocol to enhance detection of microhemorrhages, as well as diagnosis of probable CAA. They suggested a minimum field strength of 3 Tesla, using susceptibility-weighted imaging at a slice thickness of no more than 5 mm. This would offer higher resolution for spotting tiny bleeds. Many hospitals and outpatient centers have been upgrading from 1.5T to 3T scanners in the past decade, though not all have them.

Some programs are already doing this. “We’ve worked with our neuroradiologist to develop an MRI sequence with a susceptibility-weighted imaging sequence that is very sensitive for microbleeds,” Erik Musiek at Washington University in St. Louis told Alzforum.

Kozberg noted that where in the brain microbleeds are matters, as well. Leakage in deep brain regions is not linked to CAA, whereas lobar bleeds often indicate the presence of extensive vascular amyloid, she told Alzforum.

In hindsight, researchers now believe that some of the deaths in immunotherapy trials to date could have been prevented with better baseline screening or by stopping infusions sooner. For example, three ARIA-related deaths in the Phase 3 donanemab trial were described in the published data. In one case, the participant had superficial siderosis at baseline; in another, the participant developed severe ARIA on MRI after three doses of drug, and dosing was later resumed after it cleared up. No autopsies were done, according to the paper. None of the three participants was an APOE4 homozygote (Sims et al., 2023).

The FDA has reserved judgment, saying the evidence so far is inconclusive for amyloid immunotherapy causing death. In briefing documents for lecanemab approval, the agency wrote that because the two deaths discussed here occurred in the OLE, there was no placebo control for comparison. In addition, the FDA noted the existence of many confounding factors, such as other medications, stroke, and falls, that surrounded these deaths. “Any role for an interaction between lecanemab and underlying severe CAA or CAA-related inflammation/vasculitis cannot be determined,” the agency wrote. “This … limits the ability to make any recommendations regarding the use of lecanemab in subjects with CAA.” In the advisory committee meeting, clinical safety reviewer Deniz Erten-Lyons at the FDA noted that CAA often cannot be detected, and thus the risks of lecanemab use in people with CAA are not well-characterized (see FDA transcript pages 118-121). The committee recommended continued reporting of any cases of vasculitis associated with postmarket use of lecanemab.

Clinician-researchers believe caution is warranted. Stephen Salloway at Butler Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island, would like to see more training available for physicians, for example webinars on the topic, or an ARIA support line to call with questions. He also believes automated reads of MRIs could offer value to community physicians inexperienced in recognizing ARIA. For example, the company Icometrix, based in Leuven, Belgium, and in Boston, has developed machine-learning algorithms for MRI that help distinguish several neurological conditions and are FDA-approved for clinical use. “It would help clinicians to have that as a backup,” Salloway said.

How to Make Treatment Better?

Besides more rigorous baseline evaluation, researchers emphasized the importance of following patients closely during treatment, and performing an MRI if ARIA symptoms such as severe headaches show up. “I want to encourage clinicians to be attentive to these changes,” Salloway said. He noted that ARIA symptoms can mimic stroke, and stressed the importance of educating emergency-room physicians to be alert for this so they do not administer clot-busting drugs to someone on amyloid immunotherapy.

To help raise awareness, Greenberg organized an ARIA session at the International Stroke Conference to be held February 9 in Phoenix. Talks will cover mechanisms and neuropathology of ARIA, as well as how to recognize and treat it in hospitals.

What is the treatment for severe ARIA? Physicians typically administer steroids, but Iadecola noted that those do not always work. For example, the woman described in Solopova et al. received steroids, but continued to worsen. In CAA-ri, steroids do help, perhaps because they squelch production of the endogenous antibodies that are causing the problem. In ARIA caused by immunotherapy, however, antibodies are exogenous and thus not affected, Iadecola said.

“The best treatment for ARIA and the effectiveness of steroids is not currently known,” Greenberg agreed.

Kozberg noted that the vascular inflammation seen in recent case studies affected the vessel wall. This is known as Aβ-related angiitis (ABRA), and is distinct from CAA-ri, where inflammation is mostly perivascular. CAA-ri and ABRA are two subtypes of inflammatory CAA (de Souza and Tasker, 2023). ABRA is often treated more aggressively than is CAA-ri, by adding cyclophosphamide to the usual intravenous steroids. Perhaps this could be tried for ARIA, Kozberg suggested.

Iadecola recommended scientists investigate ways to calm down perivascular macrophages, perhaps by suppressing receptors that bind Aβ. “That would be a more precision approach than steroids,” he noted. That work is yet to be done, however. “Until we figure that out, screening is key,” Iadecola added. Prevention is the name of the game, Salloway agreed.

Salloway noted that more neuropathology studies from ARIA cases are in press, including one about a death in the aducanumab trial. Together, the data may provide more clues as to how to make amyloid immunotherapy safer.—Madolyn Bowman Rogers

References

Therapeutics Citations

News Citations

- Paris: Renamed ARIA, Vasogenic Edema Common to Anti-Amyloid Therapy

- Should People on Blood Thinners Forego Leqembi?

- Is ARIA an Inflammatory Reaction to Vascular Amyloid?

- Wanted: Fluid Biomarkers for CAA, ARIA

- Unlocking Blood-Brain Barrier Boosts Immunotherapy Efficacy, Lowers ARIA

Paper Citations

- Roher AE, Maarouf CL, Daugs ID, Kokjohn TA, Hunter JM, Sabbagh MN, Beach TG. Neuropathology and amyloid-β spectrum in a bapineuzumab immunotherapy recipient. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;24(2):315-25. PubMed.

- Roher AE, Cribbs DH, Kim RC, Maarouf CL, Whiteside CM, Kokjohn TA, Daugs ID, Head E, Liebsack C, Serrano G, Belden C, Sabbagh MN, Beach TG. Bapineuzumab alters aβ composition: implications for the amyloid cascade hypothesis and anti-amyloid immunotherapy. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59735. PubMed.

- Sakai K, Boche D, Carare R, Johnston D, Holmes C, Love S, Nicoll JA. Aβ immunotherapy for Alzheimer's disease: effects on apoE and cerebral vasculopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2014 Dec;128(6):777-89. Epub 2014 Sep 7 PubMed.

- Reish NJ, Jamshidi P, Stamm B, Flanagan ME, Sugg E, Tang M, Donohue KL, McCord M, Krumpelman C, Mesulam MM, Castellani R, Chou SH. Multiple Cerebral Hemorrhages in a Patient Receiving Lecanemab and Treated with t-PA for Stroke. N Engl J Med. 2023 Jan 4; PubMed.

- Castellani RJ, Shanes ED, McCord M, Reish NJ, Flanagan ME, Mesulam MM, Jamshidi P. Neuropathology of Anti-Amyloid-β Immunotherapy: A Case Report. J Alzheimers Dis. 2023;93(2):803-813. PubMed.

- Taylor X, Clark IM, Fitzgerald GJ, Oluoch H, Hole JT, DeMattos RB, Wang Y, Pan F. Amyloid-β (Aβ) immunotherapy induced microhemorrhages are associated with activated perivascular macrophages and peripheral monocyte recruitment in Alzheimer's disease mice. Mol Neurodegener. 2023 Aug 30;18(1):59. PubMed.

- Sperling RA, Jack CR, Black SE, Frosch MP, Greenberg SM, Hyman BT, Scheltens P, Carrillo MC, Thies W, Bednar MM, Black RS, Brashear HR, Grundman M, Siemers ER, Feldman HH, Schindler RJ. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities in amyloid-modifying therapeutic trials: recommendations from the Alzheimer's Association Research Roundtable Workgroup. Alzheimers Dement. 2011 Jul;7(4):367-85. PubMed.

- Schindler RJ, Carrillo MC. Output of the working group on magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities and treatment with amyloid-modifying agents. Alzheimers Dement. 2011 Jul;7(4):365-6. PubMed.

- Sims JR, Zimmer JA, Evans CD, Lu M, Ardayfio P, Sparks J, Wessels AM, Shcherbinin S, Wang H, Monkul Nery ES, Collins EC, Solomon P, Salloway S, Apostolova LG, Hansson O, Ritchie C, Brooks DA, Mintun M, Skovronsky DM, TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 Investigators. Donanemab in Early Symptomatic Alzheimer Disease: The TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2023 Aug 8;330(6):512-527. PubMed.

- de Souza A, Tasker K. Inflammatory Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy: A Broad Clinical Spectrum. J Clin Neurol. 2023 May;19(3):230-241. PubMed.

Other Citations

External Citations

Further Reading

News

- Unlocking Blood-Brain Barrier Boosts Immunotherapy Efficacy, Lowers ARIA

- Aduhelm Phase 3 Data: ARIA Is Common, Sometimes Serious

- Aduhelm Administration Remains a Trickle, ARIA a Concern

- Even Without Amyloid, ApoE4 Weakens Blood-Brain Barrier, Cognition

- Diagnosis for Inflammation in Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy

- Small Brain Bleeds Lead To Bigger Problems in Alzheimer’s

Primary Papers

- Solopova E, Romero-Fernandez W, Harmsen H, Ventura-Antunes L, Wang E, Shostak A, Maldonado J, Donahue MJ, Schultz D, Coyne TM, Charidimou A, Schrag M. Fatal iatrogenic cerebral β-amyloid-related arteritis in a woman treated with lecanemab for Alzheimer's disease. Nat Commun. 2023 Dec 12;14(1):8220. PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

Massachusetts General Hospital

The data presented in this case report continue to support the hypothesis that the mechanism underlying ARIA closely relates to CAA and likely shares many mechanistic links with CAA-related inflammation (CAA-ri). These findings emphasize the importance of accurately diagnosing concomitant CAA when considering administration of anti-amyloid immunotherapies.

Given the high resolution of postmortem MR imaging, it is not surprising that more microhemorrhages were observed post-mortem than in the in-vivo scans—this has previously been reported in patients with CAA (van Veluw et al., 2016). However, this difference does bring up an important issue regarding assessing for CAA prior to initiating anti-amyloid immunotherapies. While it is known that ~50 percent of patients with AD will have evidence of moderate to severe CAA at autopsy (Jäkel et al., 2021), it is notable that this patient met the MRI-based Boston Criteria (both the modified Boston Criteria and the recently published Boston Criteria 2.0, see Charidimou et al., 2022) for probable CAA prior to the initiation of treatment.

The recent clinical trials of passive immunization have kept exclusion criteria based on microbleeds relatively simple, excluding patients with > 4 microbleeds (on GRE sequences). However, enhancing this imaging and taking advantage of well-established MR-based imaging criteria for CAA may be a potential way to refine our understanding of ARIA risk and help patients/physicians make more informed decisions regarding their individualized risks/benefits of anti-amyloid immunotherapies.

For example, as suggested by the authors, susceptibility-weighted imaging sequences (more sensitive for microbleeds) could be used, and the location of microbleeds taken into consideration (as deep/non-lobar microbleeds are not associated with CAA). Hemorrhagic manifestations of CAA are considered very advanced stages of vessel pathology, occurring many years after initial vascular Aβ deposition (Koemans et al., 2023). Therefore, patients with evidence of lobar microbleeds are likely to have many other vessels with vascular amyloid and advanced pathology, a meaningful risk factor for ARIA.

Of note, earlier reports of patients who received active immunization with AN1792 also suggest relocation of parenchymal amyloid to the vasculature with anti-amyloid immunotherapy (Boche et al., 2008), likely an important exacerbating factor which could preferentially impact patients with pre-existing CAA given the hypothesized issues with perivascular amyloid clearance associated with this disease.

In addition to probable CAA, this patient notably had other known risk factors for ARIA, including two APOE4 alleles and recent initiation of anti-amyloid immunotherapy (similar to the case reported by Reish et al.). Given this emerging data, if the decision is made to use these therapies in these higher-risk groups, additional caution is warranted with a lower threshold for repeat MRIs in the setting of clinical symptoms (e.g. severe headache, seizure, focal neurological symptoms).

In terms of the inflammatory profile, the authors observed perivascular and transmural T-cell infiltration and identified macrophages/microglia associated with vascular amyloid. Similar findings have been observed in prior ARIA case reports including from Reish et al. (2023) and in older studies of active immunization with AN1792 (Nicoll et al., 2003). Additionally, similar neuropathological findings are observed in CAA-ri. A recent PET study also demonstrated microglial activation in the setting of CAA-ri (Piazza et al., 2022).

Notably, in a recent preclinical study using mouse models of AD, 3D6 (murine version of bapineuzumab) administration led to the formation of antibody immune complexes with vascular Aβ, which in turn led to perivascular macrophage activation (Taylor et al., 2023). While this case report does not differentiate between macrophage infiltration from the periphery vs. resident perivascular macrophages of the brain (or between macrophages and microglia), these findings again suggest the importance of perivascular macrophages in the vascular inflammation associated with ARIA.

Finally, the vascular inflammation observed in this case (and the case reported by Reish et al.) was severe, with transmural inflammation and multinucleated giant cells. While limited data exists, in cases of Aβ-related angiitis (ABRA), distinguished from CAA-ri by the presence of transmural inflammation, more aggressive immunosuppression is often considered (e.g., adding cyclophosphamide to IV steroids, echoing treatments used for primary angiitis of the CNS). More aggressive immunosuppression may be a consideration in treatment for severe ARIA in the future.

References:

van Veluw SJ, Charidimou A, van der Kouwe AJ, Lauer A, Reijmer YD, Costantino I, Gurol ME, Biessels GJ, Frosch MP, Viswanathan A, Greenberg SM. Microbleed and microinfarct detection in amyloid angiopathy: a high-resolution MRI-histopathology study. Brain. 2016 Dec;139(Pt 12):3151-3162. Epub 2016 Sep 19 PubMed.

Jäkel L, De Kort AM, Klijn CJ, Schreuder FH, Verbeek MM. Prevalence of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2021 May 31; PubMed.

Charidimou A, Boulouis G, Frosch MP, Baron JC, Pasi M, Albucher JF, Banerjee G, Barbato C, Bonneville F, Brandner S, Calviere L, Caparros F, Casolla B, Cordonnier C, Delisle MB, Deramecourt V, Dichgans M, Gokcal E, Herms J, Hernandez-Guillamon M, Jäger HR, Jaunmuktane Z, Linn J, Martinez-Ramirez S, Martínez-Sáez E, Mawrin C, Montaner J, Moulin S, Olivot JM, Piazza F, Puy L, Raposo N, Rodrigues MA, Roeber S, Romero JR, Samarasekera N, Schneider JA, Schreiber S, Schreiber F, Schwall C, Smith C, Szalardy L, Varlet P, Viguier A, Wardlaw JM, Warren A, Wollenweber FA, Zedde M, van Buchem MA, Gurol ME, Viswanathan A, Al-Shahi Salman R, Smith EE, Werring DJ, Greenberg SM. The Boston criteria version 2.0 for cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a multicentre, retrospective, MRI-neuropathology diagnostic accuracy study. Lancet Neurol. 2022 Aug;21(8):714-725. PubMed.

Koemans EA, Chhatwal JP, van Veluw SJ, van Etten ES, van Osch MJ, van Walderveen MA, Sohrabi HR, Kozberg MG, Shirzadi Z, Terwindt GM, van Buchem MA, Smith EE, Werring DJ, Martins RN, Wermer MJ, Greenberg SM. Progression of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a pathophysiological framework. Lancet Neurol. 2023 Jul;22(7):632-642. Epub 2023 May 23 PubMed.

Boche D, Zotova E, Weller RO, Love S, Neal JW, Pickering RM, Wilkinson D, Holmes C, Nicoll JA. Consequence of Abeta immunization on the vasculature of human Alzheimer's disease brain. Brain. 2008 Dec;131(Pt 12):3299-310. PubMed.

Reish NJ, Jamshidi P, Stamm B, Flanagan ME, Sugg E, Tang M, Donohue KL, McCord M, Krumpelman C, Mesulam MM, Castellani R, Chou SH. Multiple Cerebral Hemorrhages in a Patient Receiving Lecanemab and Treated with t-PA for Stroke. N Engl J Med. 2023 Jan 4; PubMed.

Nicoll JA, Wilkinson D, Holmes C, Steart P, Markham H, Weller RO. Neuropathology of human Alzheimer disease after immunization with amyloid-beta peptide: a case report. Nat Med. 2003 Apr;9(4):448-52. PubMed.

Piazza F, Caminiti SP, Zedde M, Presotto L, DiFrancesco JC, Pascarella R, Giossi A, Sessa M, Poli L, Basso G, Perani D. Association of Microglial Activation With Spontaneous ARIA-E and CSF Levels of Anti-Aβ Autoantibodies. Neurology. 2022 Sep 20;99(12):e1265-e1277. Epub 2022 Aug 8 PubMed.

Taylor X, Clark IM, Fitzgerald GJ, Oluoch H, Hole JT, DeMattos RB, Wang Y, Pan F. Amyloid-β (Aβ) immunotherapy induced microhemorrhages are associated with activated perivascular macrophages and peripheral monocyte recruitment in Alzheimer's disease mice. Mol Neurodegener. 2023 Aug 30;18(1):59. PubMed.

University of Southampton School of Medicine

This study highlights the urgent need for a better understanding of the mechanism for the development of ARIA. Postmortem analysis showed severe cerebral amyloid angiopathy accompanied by perivascular inflammatory infiltrates. The findings offer support for the hypothesis that following immunotherapy against Aβ, the solubilized Aβ from plaques becomes entrapped in the pathways for intramural periarterial drainage (IPAD).

Apart from the urgent need to clarify the mechanisms of ARIA, there is an unmet need for determining the patient population with IPAD pathways that are not compromised and able to clear the solubilized Aβ from plaques with no risk of developing CAA or ARIA.

University of Milano-Bicocca

This case further confirms the abundant evidence we published in the last years suggesting radiographic ARIA-E in immunotherapy trials is the downstream and, in some ways “late-stage,” manifestation of iatrogenic CAA-related inflammation (CAA-ri).

In the CAA-ri framework, we previously described a regional and temporal association between subacute radiographic ARIA-E and microglial activation, by in vivo PET. This association was specifically observed only within ARIA-E, while no or negligible microglial activation was observed within age-related white matter changes (ARWMC).

The neuropathological evidence reported here, of intense immunoreactivity for the microglial marker IBA1, is remarkably similar to our in vivo PET findings.

Moreover, as we formerly reported in CAA-ri, these peaks of increased microglial reactivity co-localized with ARIA-E were specifically observed only in patients with AD + CAA comorbid disease, while no co-localization between microglial and ARIA-E was observed in patients with CAA only, i.e., without AD co-pathology by means of positive ATN biomarkers.

Most intriguingly, all CAA-ri had raised CSF levels of anti-Aβ (auto)antibodies at (sub)acute presentation of ARIA-E, irrespective of ARIA-E clinical or radiological severity or their CAA severity or comorbidity with AD. The antibody concentration markedly reduced post-corticosteroid therapy, in parallel with the clinic-radiological resolution of ARIA-E, and markedly reduced microglial activation.

I am pleased to see that all of these findings can be in some way replicated here, in this case. This further reinforces our evidence that ARIA-E is the imaging manifestation of the complex (auto)immune biological mechanisms of CAA-ri.

In this framework, we do not need a new term to define the presentation of these ARIA-E side events, whether they are symptomatic or not, as they should be already called iatrogenic CAA-ri. Instead, the terms ARIA-E and ARIA-H should be used only to report the presence of these types of imaging abnormalities on MRI, avoiding any potential association with the presentation of clinical symptoms and/or clinical severity.

The term ARIA, in fact, was not intended for that. Indeed, it is quite clear that the MRI imaging severity of ARIA-E has no associations with its clinical severity at presentation or its prognosis after an ARIA-E index event has occurred.

In anticipation of a large use of monoclonal antibodies for AD immunotherapy in real-world clinical practice, precision medicine approaches will be key. The discovery and validation of additional fluid-based biomarkers of ARIA and CAA-ri to complement and overcome current limitations of MRI should represent an international priority.

References:

Piazza F, Caminiti SP, Zedde M, Presotto L, DiFrancesco JC, Pascarella R, Giossi A, Sessa M, Poli L, Basso G, Perani D. Association of Microglial Activation With Spontaneous ARIA-E and CSF Levels of Anti-Aβ Autoantibodies. Neurology. 2022 Sep 20;99(12):e1265-e1277. Epub 2022 Aug 8 PubMed.

Kelly L, Brown C, Michalik D, Hawkes CA, Aldea R, Agarwal N, Salib R, Alzetani A, Ethell DW, Counts SE, de Leon M, Fossati S, Koronyo-Hamaoui M, Piazza F, Rich SA, Wolters FJ, Snyder H, Ismail O, Elahi F, Proulx ST, Verma A, Wunderlich H, Haack M, Dodart JC, Mazer N, Carare RO. Clearance of interstitial fluid (ISF) and CSF (CLIC) group-part of Vascular Professional Interest Area (PIA), updates in 2022-2023. Cerebrovascular disease and the failure of elimination of Amyloid-β from the brain and retina with age and Alzheimer's dise. Alzheimers Dement. 2024 Feb;20(2):1421-1435. Epub 2023 Oct 28 PubMed.

Zedde M, Pascarella R, Piazza F. CAA-ri and ARIA: Two Faces of the Same Coin?. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2023 Feb;44(2):E13-E14. Epub 2023 Jan 12 PubMed.

Antolini L, DiFrancesco JC, Zedde M, Basso G, Arighi A, Shima A, Cagnin A, Caulo M, Carare RO, Charidimou A, Cirillo M, Di Lazzaro V, Ferrarese C, Giossi A, Inzitari D, Marcon M, Marconi R, Ihara M, Nitrini R, Orlandi B, Padovani A, Pascarella R, Perini F, Perini G, Sessa M, Scarpini E, Tagliavini F, Valenti R, Vázquez-Costa JF, Villarejo-Galende A, Hagiwara Y, Ziliotto N, Piazza F. Spontaneous ARIA-like Events in Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy-Related Inflammation: A Multicenter Prospective Longitudinal Cohort Study. Neurology. 2021 Nov 2;97(18):e1809-e1822. Epub 2021 Sep 16 PubMed.

St. Michael's Neurology and Pain Medicine

As we continue to struggle with the challenges of treating CAA-RI, the potential role of immunosuppressive therapy emerges as a critical area of focus.

For high-risk groups undergoing treatment with Leqembi, particularly those identified as probable cases of CAA-RI (Auriel et al., 2016), the implementation of early immunosuppressive therapy would be an important consideration. This approach warrants exploration through randomized clinical trials. In a retrospective study examining a cohort of patients with CAA-RI, data indicates that initiating immunosuppressive therapy early not only enhances the initial response to the disease but also appears to decrease the probability of its recurrence (Regenhardt et al., 2020).

The prevailing evidence suggests that an autoimmune response to Aβ drives CAA-RI. This hypothesis is substantiated by clinical and imaging similarities observed in ARIA, initially detected during bapineuzumab's clinical trials. ARIA manifests in two forms: ARIA-E, marked by either focal or widespread vasogenic edema visible on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) imaging, and ARIA-H, characterized by cerebral microbleeds or cortical superficial siderosis, detectable in T2-weighted gradient-echo/susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) scans. These radiological signs are also common indicators of CAA-RI. Interestingly, almost half of the patients with ARIA-E also develop ARIA-H, and these conditions frequently co-occur in the same locations.

In several autoimmune types of vasculopathy, IL-6 plays a pathological role in the inflammatory response in both the vessel wall and the systemic circulation. Would Tocilizumab be a good agent to try? This is a humanized monoclonal antibody that competitively inhibits IL-6 by binding it to circulating and membrane-bound IL-6 receptors. The first reported randomized controlled trial on the efficacy of tocilizumab in giant cell arteritis, in addition to glucocorticoids, found it efficacious with a higher relapse-free survival (Villiger et al., 2016). I wonder if this observation could be mirrored in patients with complications of CAA-RI, although the exact inflammatory cascade behind CAA-RI remains unclear. Another report suggested administration of steroids with cyclophosphamide or azathioprine (Grasso et al., 2021).

Patients exhibiting rapid cognitive deterioration, headaches, seizures, or specific neurological deficits, alongside patchy or widespread hyperintensity in T2 or FLAIR sequences or showing clear signs of lobar microbleeds or cortical superficial siderosis in susceptibility-weighted imaging, likely indicate CAA-RI. In my view, these patients are prime candidates for prompt immunosuppressive treatment. Furthermore, individuals displaying elevated inflammatory markers or increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP) levels are also at heightened risk for CAA-RI. They tend to be more susceptible to complications and might potentially benefit significantly from immunosuppressive therapies. In the absence of high-quality randomized trials, I am interested in the readership's opinions on the most effective management strategies for these patients.

References:

Auriel E, Charidimou A, Gurol ME, Ni J, Van Etten ES, Martinez-Ramirez S, Boulouis G, Piazza F, DiFrancesco JC, Frosch MP, Pontes-Neto OV, Shoamanesh A, Reijmer Y, Vashkevich A, Ayres AM, Schwab KM, Viswanathan A, Greenberg SM. Validation of Clinicoradiological Criteria for the Diagnosis of Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy-Related Inflammation. JAMA Neurol. 2016 Feb;73(2):197-202. PubMed.

Regenhardt RW, Thon JM, Das AS, Thon OR, Charidimou A, Viswanathan A, Gurol ME, Chwalisz BK, Frosch MP, Cho TA, Greenberg SM. Association Between Immunosuppressive Treatment and Outcomes of Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy-Related Inflammation. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Jun 22; PubMed.

Villiger PM, Adler S, Kuchen S, Wermelinger F, Dan D, Fiege V, Bütikofer L, Seitz M, Reichenbach S. Tocilizumab for induction and maintenance of remission in giant cell arteritis: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2016 May 7;387(10031):1921-7. Epub 2016 Mar 4 PubMed.

Grasso D, Castorani G, Borreggine C, Simeone A, De Blasi R. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy related inflammation: A little known but not to be underestimated disease. Radiol Case Rep. 2021 Sep;16(9):2514-2521. Epub 2021 Jul 3 PubMed.

TrueBinding

Immunization with fAβ42 (AN1792) results in a nearly complete absence of Aβ plaque deposits, both in mice that were vaccinated prior to the onset of amyloid deposition and in animals that were vaccinated after amyloid deposition was well underway. However, human clinical trials were halted due to a high incidence of meningioencephalitis that is presumably due to an auto inflammatory reaction to immunization with human Aβ. Overcoming the auto inflammatory side effects while maintaining an effective immune response is a hurdle that must be overcome for the development of a human vaccine for AD.

This study clearly shows the auto inflammatory side effects of lecanemab. Since the conformation dependent immune response to Aβ oligomer and Aβ fibril antigens are distinct while the immune response to the oligomer mimic antigens is common, this suggests that the increased incidence of micro hemorrhage may be due to sequence-specific antibodies that are common to the Aß containing antigens.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.