Tangles Turn Neuronal Membranes Inside Out, Give Microglia License to Eat Their Fill

Quick Links

In the drama of neurodegenerative disease, neurons meet an untimely end, but scientists don’t know what ultimately does them in. Now, researchers led by Maria Grazia Spillantini at the University of Cambridge, England, U.K., report it is microglia, at least in tauopathies. Neurons containing tau tangles present phosphatidylserine, a lipid normally reserved for the inner cell membrane, on their surface. This attracts microglia, which devour neurons whole, the authors contend. They propose that preventing this phagocytosis could bide time for other tau-neutralizing treatments to save neurons. “Ours is the first study to shed light on a new mechanism of natural neuronal cell death in neurodegeneration, showing that neurons that form tau filamentous aggregates without any outside help instigate the process of their being eaten alive,” said Aviva Tolkovsky, a corresponding author on the August 21 Cell Reports paper detailing the findings. “If this happens in the human brain it could have important implications; blocking phagocytosis could rescue living neurons, which might then benefit from therapies that reduce tau toxicity.”

- Filaments of mutant tau give rise to reactive oxygen species in neurons.

- The neurons display a phospholipid signal marking them for phagocytosis.

- Microglia engulf neurons while they are still alive.

Cell surface phosphatidylserine is a known “eat me” signal for microglia. Cells that have undergone apoptosis, or programmed cell death, display the lipid on their outer membranes (for a review see Elmore, 2007). First author Jack Brelstaff and colleagues wondered if apoptosis figured into cell death in tauopathies. They cultured dorsal root ganglion cells from five-month-old mice that expressed P301S tau, a variant that causes frontotemporal dementia, and tested them for activated caspase-3, a major instigator of apoptosis, and phosphatidylserine. They found no evidence of the former but plenty of the latter on the surface of neurons that were packed with tau fibrils. Even in the absence of classic apoptosis, was this “eat me” signal giving microglia the green light to feast on the neurons?

To find out, the researchers co-cultured the P301S neurons with microglia. Sure enough, neurons with phosphatidylserine on their surfaces wound up inside the phagocytes. Microglia had clearly been enticed, as they spewed out a protein that goes by the mouthful opsonin milk-fat-globule EGF-factor-8. MFGE8 acts as a protein “glue” that binds microglia to phosphatidylserine. Microglia also secreted nitric oxide, a sign they were activated. After four days, more than half the neurons disappeared and tau aggregates turned up in the microglia. However, if the authors either masked the phosphatidylserine signal or blocked production of nitric oxide, which is essential for microglial phagocytosis, they could keep the neurons alive. Chemicals that scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) kept phosphatidylserine inside the neurons. ROS are known activators of transporters that flip the phospholipid to the outer membrane.

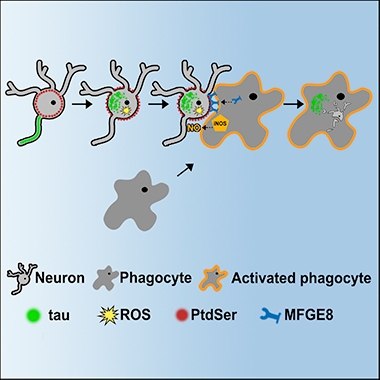

Eaten Alive.

When misfolded tau builds up in neurons, phosphatidylserine flips to the outside of the cell membrane, signaling microglia to chow down. The lipid switch depends on reactive oxygen species flip and the phagocytosis on microglial MFGE8, which anchors them to the neuron membrane. [Courtesy of Brelstaff et al., 2018.]

Is the same mechanism of cell death relevant to human tauopathies? Analysis of postmortem brain tissue from patients with different tau mutations, as well as those with Pick’s disease, suggest that it might be. The researchers found more MFGE8 in the frontal cortices of the tauopathy samples compared with samples from age-matched controls or from people with TDP-43 pathology. “This mechanism seems related to the presence of tau aggregates,” said Spillantini.

“I find the data very convincing,” wrote Marc Diamond, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, to Alzforum. “It gives us insight into a relationship between microglia and sick neurons, and how the glia might play a role in eliminating damaged cells.” However, he doubted that blocking phagocytosis would be a good therapeutic strategy, as it also clears compromised cells and debris that might otherwise clutter the brain.

Going forward, the authors want to study how ROS flips phosphatidylserine and determine what happens to tau once engulfed by the microglia. Previous studies suggest microglia can contribute to the spread of toxic tau in the brain (Oct 2015 news; Maphis et al., 2015). It will also be important to demonstrate this mechanism in cultured human neurons from the brain, said Spillantini, but getting tau fibrils established in those cells has proven difficult, she said.—Gwyneth Dickey Zakaib

References

Research Models Citations

News Citations

Paper Citations

- Elmore S. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol. 2007 Jun;35(4):495-516. PubMed.

- Maphis N, Xu G, Kokiko-Cochran ON, Jiang S, Cardona A, Ransohoff RM, Lamb BT, Bhaskar K. Reactive microglia drive tau pathology and contribute to the spreading of pathological tau in the brain. Brain. 2015 Jun;138(Pt 6):1738-55. Epub 2015 Mar 31 PubMed.

Further Reading

Primary Papers

- Brelstaff J, Tolkovsky AM, Ghetti B, Goedert M, Spillantini MG. Living Neurons with Tau Filaments Aberrantly Expose Phosphatidylserine and Are Phagocytosed by Microglia. Cell Rep. 2018 Aug 21;24(8):1939-1948.e4. PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

This is an intriguing study. Externalization of phosphatidylserine is an early indication of apoptosis, which would be anticipated to recruit microglial “attack.” Blocking this early externalization by antioxidants is reminiscent of Mark Smith’s hypothesis (although directed at Aβ rather than tau abnormalities) that the system is mounting attempts at neuroprotection. The authors are spot on in stating that suppression of microglial activation in this instance must be accompanied by therapeutic approaches to curtail tau accumulation, since sparing affected neurons will otherwise promote the recently documented neuronal-neuronal transfer of tau. All in all, this study highlights the complexity of events that bring about and/or result from initial stages of neurodegeneration, and underscore that therapeutic approaches must be equally as complex.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.