Donanemab Data Anchors Upbeat AAIC

Quick Links

Change was in the air at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, held July 16-20 in Amsterdam. With the first treatment in 20 years having just earned traditional approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, another with accelerated approval, and a third with positive Phase 3 data, Alzheimer’s researchers marked the end of a long drought, and made plans to build on these gains. Some 7,500 people attended in person, and another 3,500 viewed talks online. A third of attendees were under 35, more than 60 percent were women, and almost a fifth were from low- and middle-income countries, noted the association’s Maria Carrillo.

- The clinical benefit of donanemab increased over 18 months.

- People at earlier disease stages, with fewer tangles, benefited more.

- Unlike in Phase 2, tangle accumulation did not slow.

“I’ve never experienced such a positive vibe at AAIC,” said Philip Scheltens, who has been part of this conference for the last 35 years. “We’ve waited so long [to have new treatments], and now we’re there.” Scheltens, newly retired from leading the Alzheimer’s Center at VU University Medical Center in the meeting’s host city, received the Alzheimer’s Association’s Bengt Winblad Lifetime Achievement Award at AAIC. Many subsequent sessions were introduced by his successor, Wiesje van der Flier, who shares directorship of the Alzheimer’s Center with Yolande Pijnenburg.

In a further sign of how drug approvals are changing the field, the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced its plan to end restrictions on covering amyloid PET scans July 18 during AAIC. In effect since 2013, the previous policy had limited beneficiaries to a single scan per lifetime, and only for those participating in a clinical trial (Jan 2013 news; Oct 2013 news). In its proposed decision memo, the agency noted that this once-per-lifetime restriction was no longer appropriate, given the development of anti-amyloid treatments.

Against this backdrop, sessions in Amsterdam featured numerous talks on amyloid immunotherapy. Other notable topics included Down’s syndrome—a genetic form of Alzheimer's that could potentially be treated with such antibodies but has not been studied for that purpose—and anti-tau antibodies and their potential for concurrent trials. A symposium on proposed revisions to the NIA-AA criteria for diagnosing AD drew keen interest. So did sessions on reviving BACE inhibitors, inflammation and vascular contributions to dementia, ADRD biomarkers beyond Aβ and p-tau, the LEAD cohort of early onset AD, APOE research, and many other topics (see upcoming conference stories).

This story summarizes the first in-depth look at Phase 3 data from donanemab, which were discussed July 17 in Amsterdam, and published in JAMA the same day. In Amsterdam, Eli Lilly’s Mark Mintun said the company has applied for traditional approval from the FDA, and will file in other countries this year. Lilly has begun a new safety and efficacy trial, Trailblazer-Alz5, focused on countries outside the U.S.

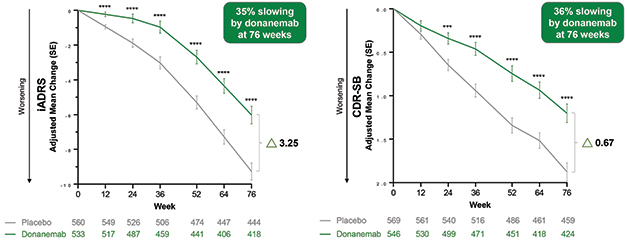

Diverging Curves? In the primary analysis population, donanemab (green) slowed cognitive decline compared to the placebo group (gray) on the iADRS (left) and CDR-SB (right), with curves continuing to diverge over 18 months. [Courtesy of Eli Lilly.]

Donanemab Benefit Robust, Grows Over Time

Lilly had released Phase 3 top-line results from Trailblazer-Alz2 two months ago, reporting that donanemab slowed decline on the primary and all secondary clinical endpoints by about a third in the primary analysis population, who had low-to-intermediate tau tangle loads (May 2023 news). In Amsterdam, Lilly’s John Sims filled in details. At 18 months, the absolute difference between treatment and control groups was 3.25 points on the iADRS, and 0.67 on the CDR-SB. The latter was slightly larger than the 0.45 points seen with lecanemab, and the 0.53 points notched in the one positive aducanumab trial. Those trials did not use the iADRS.

The Trailblazer-Alz2 cohort was slightly further along in the disease compared to those in other trials, Mintun noted. Participants were about two years older, at an average age of 74. Their baseline MMSE was 23, their plaque load 102 centiloids. These numbers were similar to participants in the negative gantenerumab Phase 3 trials, but more advanced than the population in the positive lecanemab Phase 3 trial, which had an average MMSE of 26 and amyloid load of 76 centiloids (Dec 2022 conference news).

The difference between the donanemab and control groups became statistically significant as early as three months for the iADRS, and at six months for the CDR-SB. The curves continued to separate over 18 months, as expected for a disease-modifying therapy, Mintun said. At 12 months, the numerical difference between treatment and placebo groups was 2.62 for the iADRS and 0.59 for the CDR-SB, both less than the difference at 18 months. The researchers are continuing to follow participants in a further 18-month open-label extension, which is still blinded to the original treatment groups. This will generate data on how the treatment effect evolves over three years.

In Amsterdam, several scientists continued their argument for measuring delay in progression in units of time, rather than numerical differences or percent slowing of decline (Apr 2023 conference news). On this “time saved” scale, donanemab delayed progression on the iADRS by 4.5 months, and on the CDR-SB by 7.5 months, Liana Apostolova of Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis reported in Amsterdam.

The findings were reported to be robust to sensitivity analyses. Efficacy results did not much change when the analyses were adjusted to account for dropouts, when excluding participants who had ARIA, or when using different statistical methods. In all scenarios, donanemab slowed progression between 33 to 40 percent, Sims said.

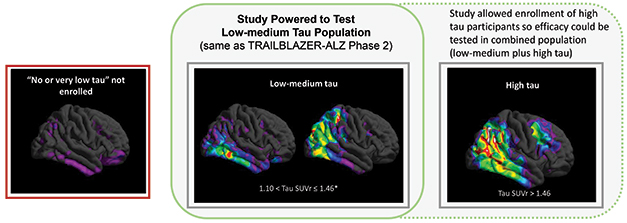

Slice and Dice by Tau. The Trailblazer-Alz2 trial focused on people with low to intermediate tangle load (middle), the only statistically powered group. Gains were smaller in a high-tau group (right). People with very little tau PET signal (left) were not enrolled, nor followed observationally. [Courtesy of Eli Lilly.]

Treatment Effect Apparent in Early Disease, at Intermediate Tau Loads

In prespecified analyses of the primary outcome data, donanemab appeared to work best at a narrowly defined disease stage. The clinical benefit was largest in the subgroup with mild cognitive impairment. Their decline slowed by 60 percent on the iADRS and 46 percent on the CDR-SB. Grouping participants by age revealed slightly more benefit in those under 75, with decline slowed by 48 percent on the iADRS and 45 percent on the CDR-SB.

Other factors did not seem to matter. The researchers found no difference between men and woman, unlike in the Phase 3 gantenerumab trials, which had a greater effect in men (Apr 2023 conference news). In those trials, women at baseline had worse tau tangles than men, whereas Trailblazer-Alz2 selected participants based on tangle load, resulting in more uniformity on this measure.

Racial and ethnic subgroups were too small to draw conclusions. Lilly has added an ongoing safety addendum to the trial and is using this to try to boost diversity, Mintun noted. There was no difference between APOE4 heterozygotes and noncarriers. The treatment benefit appeared to be slightly less in APOE4 homozygotes, but this subgroup was small and underpowered.

Tangle load did matter, however. The RCT trial population, comprising 1,182 people and used for all the above analyses, had baseline tau PET scans between 1.10 and 1.46 SUVr. Trailblazer-Alz2 enrolled an additional 554 people with scans above 1.46. This high-tau subgroup notched barely 20 percent slowing of decline on the CDR-SB, and below 10 percent on the iADRS. The former was statistically significant, the latter not, though Sims noted that this subgroup was not powered to show significance. Baseline amyloid loads were the same regardless of tangle burden.

This curation of a treatment group by tau PET drew both praise and questions. Christopher van Dyck of Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, called these staging data valuable but noted that as many as a quarter of people with early AD have tau PET loads below 1.10 SUVr. Should this group be treated with donanemab? This registration trial gives no data on this question, as it excluded them.

Sims noted that this population, which Lilly considers to be basically “no tau,” is being evaluated in Trailblazer-Alz3, which enrolls people at the preclinical stage of disease. That trial is not expected to read out until the end of 2027 (Jul 2021 news). This answer did not fully satisfy everyone. In hallway talk at AAIC, several clinician-researchers said they'd prefer to also have data on how donanemab performs in people with mild symptoms and very low tau, many of whom will seek treatment at memory clinics.

Others asked whether tau PET scans will be necessary before treatment with donanemab, so that treating physicians can target the same population as those who benefitted in the trial. Sims argued that this is not needed, given that the combined intermediate- and high-tau groups still showed a statistically significant treatment benefit. Oskar Hansson of Lund University, Sweden, who analyzed biomarker data for Lilly, noted that because people with high tangle loads have a different risk-benefit ratio for treatment, it would be helpful to test for tau burden before prescribing anti-amyloid antibodies. Ideally, this would be done with a blood test rather than tau PET, due to the high cost and limited availability of the latter. Such plasma tests are in development, but not yet broadly available.

Most Biomarkers Moved Toward Normal, But Tangles Stayed Put

The biomarker data from this trial shown at AAIC largely tracked with the clinical findings. Results were similar in the low-to-intermediate tau group, and in the combined analysis with the high-tau group included. As expected, donanemab rapidly removed an average of 88 centiloids of plaque over 18 months. The drop was fastest in the first six months, with a third of participants becoming amyloid-negative then. By the end of the trial, 80 percent had crossed this threshold.

This is faster than with aducanumab. In Amsterdam, Lilly’s Andrew Pain reported 12-month data from the head-to-head comparison of these two drugs in the open-label Trailblazer-Alz4 trial. Six-month data had shown faster clearance with donanemab, in part due to its quicker titration to the effective dose (Dec 2022 conference news). That pattern continued, with donanemab removing 80 centiloids compared to aducanumab's 56, by one year. In this study, 70 percent of people taking donanemab were amyloid-negative by one year, compared with 22 percent on aducanumab.

In the Phase 3 study, plasma tau biomarkers followed plaque. Plasma p-tau181 dropped almost 20 percent on drug, p-tau217, 40 percent. In keeping with the subgroup analyses showing more clinical benefit at earlier stages, people who were in the lowest p-tau217 tertile at baseline did best, declining on the CDR-SB by 46 percent less than placebo, compared with 27 percent less for those with higher baseline p-tau217. This post hoc analysis used the combined tau groups.

Plasma GFAP, a marker of inflammation, fell 21 percent on drug. Plasma NfL, thought to denote neurodegeneration, was mystifying. It initially rose in the donanemab group, before dropping back to slightly below baseline levels by 18 months. Sims noted that this marker varies greatly from one person to another, but did not show spaghetti plots.

As in other amyloid immunotherapy trials, brain volume decreased on donanemab, though hippocampal volume loss resembled that on placebo. The field is grappling with what this accelerated shrinkage means (Apr 2023 news). At AAIC, too, the discussion reprised current arguments that global volume loss perhaps reflects cortical “pseudo-atrophy” as amyloid and attendant inflammation decrease, whereas the hippocampus has little amyloid to begin with.

The most surprising and, to some, concerning finding was that donanemab did not affect tangle growth as measured by tau PET. In Phase 2, the antibody had appeared to slow, though not stop, tangle accumulation in the frontal cortex, with a trend toward slowing in the parietal and temporal lobes (Mar 2021 conference news). In the Phase 3 trial, the tau PET curves of placebo and treatment groups were superimposed.

Hansson noted that ongoing regional analyses may yet surface subtle effects. A post hoc analysis of these Phase 3 data suggested that participants who became amyloid-negative during the trial had less tangle accumulation than those who remained amyloid-positive, Hansson added. Here, too, 18 months of additional study may be instructive.

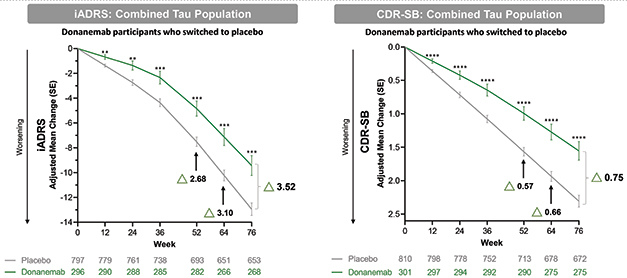

Staying Power. In participants who stopped donanemab after having dipped below the amyloid threshold by one year, trial outcomes continued to diverge from those who had always been on placebo (arrows). [Courtesy of Eli Lilly.]

What Happens When Treatment Stops?

A unique aspect of donanemab is that treatment stops once plaque load drops below the positivity threshold. In Trailblazer-Alz2, this happened in two-thirds of participants across both tau groups. What did this do to their subsequent clinical progression?

To answer this, Lilly researchers analyzed nearly 300 people who became amyloid-negative at an average of 47 weeks. Their clinical progression continued to diverge from the placebo group, reaching a difference of 3.52 points on the iADRS and 0.75 on the CDR-SB by 18 months, slightly larger than the overall trial benefit.

In Amsterdam, Lilly’s Sergey Shcherbinin presented data on plaque re-accumulation in participants of the earlier Phase 2 study. Analyzing 47 people who became amyloid-negative, with an average final plaque load of 4.7 centiloids, Shcherbinin found that they added about 2 centiloids over the following year. This is similar to the rate of plaque accumulation in the ADNI observational study, even though this trial population has higher tangle loads on average than the ADNI cohort, Shcherbinin noted. This rate was the same regardless of how much amyloid people had cleared, or how low on the centiloid scale they got after a course of donanemab.

Adding data from the Phase 3 trial upped the re-accumulation estimate to 2.8 centiloids per year. At this clip, it would take about five years for a person to become amyloid-positive again after clearance, Shcherbinin said.

ARIA: Still a Fly in the Ointment

The risk of ARIA remains a big concern. In its trials thus far, donanemab had ARIA rates in between the 12 percent on lecanemab and 33 percent on aducanumab, with about one-quarter of people on drug developing it. Six percent of people in Trailblazer-Alz2 developed symptoms from ARIA. In almost 2 percent of participants, nearly all of them APOE4 carriers, these symptoms were considered serious, noted Stephen Salloway of Butler Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island. The risk of ARIA was the same in people taking anticoagulant or anti-platelet medication as in the cohort overall.

As with lecanemab, the risk of macrohemorrhage was higher on drug, doubling from 0.2 to 0.4 percent. Three people on donanemab died from brain bleeds during the trial. Two of them were heterozygous APOE4 carriers and developed severe ARIA-E, Salloway said. The third was not a carrier, but had superficial siderosis at baseline, a sign of previous brain hemorrhages. None were on anticoagulants.

Numerous talks in Amsterdam grappled with how to predict the occurrence of ARIA, with a growing number of scientists tying it to cerebral amyloid angiopathy and its attendant inflammation (see upcoming AAIC story).—Madolyn Bowman Rogers

References

News Citations

- Not So Fast: Amyloid PET Needs More Data Before Insurance Pays

- Alzheimer’s Community Mobilizes to Show Benefits of Amyloid Scans

- And Then There Were Three: Donanemab Phase 3 Trial Positive

- Gantenerumab Mystery: How Did It Lose Potency in Phase 3?

- Next Goals for Immunotherapy: Make It Safer, Less of a Hassle

- What Happens After Amyloid Plaque Removal? Who Benefits Most?

- Can Donanemab Prevent AD? Phase 3 TRAILBLAZER-ALZ3 Aims to Find Out

- Donanemab Mops Up Plaque Faster Than Aduhelm

- What About the Brain Shrinkage Seen with Aβ Removal?

- Donanemab Confirms: Clearing Plaques Slows Decline—By a Bit

Therapeutics Citations

External Citations

Further Reading

Primary Papers

- Sims JR, Zimmer JA, Evans CD, Lu M, Ardayfio P, Sparks J, Wessels AM, Shcherbinin S, Wang H, Monkul Nery ES, Collins EC, Solomon P, Salloway S, Apostolova LG, Hansson O, Ritchie C, Brooks DA, Mintun M, Skovronsky DM, TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 Investigators. Donanemab in Early Symptomatic Alzheimer Disease: The TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2023 Aug 8;330(6):512-527. PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

Lund University

It is remarkable that we now have several anti-amyloid therapies that have been proven to slow down the disease progression of Alzheimer’s disease when initiated in amyloid-positive patients with amnestic MCI or mild dementia. While the donanemab Phase 2 and 3 trials required elevated signals in both amyloid- and tau-PET scans for enrolment, I think that a person with MCI who is amyloid-positive, but yet tau-PET-negative, should also have the opportunity to receive donanemab treatment if their cognitive symptoms are considered to be caused by AD. To me, there is no compelling reason to believe that donanemab should differ from lecanemab in this regard, especially since the results from the donanemab trials even suggested greater relative treatment benefits for patients in earlier disease stages. Therefore, a biomarker reflecting Aβ pathology, such as amyloid-PET, CSF Aβ42/p-tau, or plasma p-tau217/np-tau217, would, to my mind, suffice to confirm the presence of AD pathology in this clinical scenario, where the dementia expert deems AD to be the most likely cause of the patient's cognitive impairment.

That said, accumulating evidence from both the donanemab and lecanemab trials indicates that AD patients with lower tau load, as determined by tau-PET imaging, respond even more favorably to anti-amyloid immunotherapies, without an increase in the risks of ARIA (amyloid-related imaging abnormalities). Consequently, the benefit/risk ratio for anti-amyloid immunotherapies is likely to be further enhanced in AD populations who do not yet exhibit a high tau load. As a result, knowledge of the individual patient's tau load could facilitate a more informed discussion between the treating physician and the patient before initiating treatment, similar to how information on the patient's APOE4 genotype informs discussions regarding the risk of ARIA. However, in most memory clinics, conducting tau-PET scans for all AD patients eligible for anti-amyloid immunotherapies is not currently feasible. Nevertheless, there is hope that we will soon have access to a blood test that can indicate whether a patient has a high tau load in the brain or not.

These data are a big step forward toward effective treatment and prevention in AD. Together with results from previous clinically effective and ineffective amyloid-modulating antibodies and low molecular-weight compounds, we should now be positioned to address critical questions toward the design of an optimal Aβ therapeutic in AD:

Building on the Aβ dysfunction model: could we set up a refined pharmacokinetic model for target coverage of drug candidates focusing on early misfolded amyloid species at synaptic sites, considering limited brain availability of antibodies and small molecules?

This strategy should help rationalize the design of the optimal amyloid beta based therapeutic, before we start tau-based combination treatments in clinical trials.

References:

Hillen H. The Beta Amyloid Dysfunction (BAD) Hypothesis for Alzheimer's Disease. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:1154. Epub 2019 Nov 7 PubMed.

Zhou B, Lu JG, Siddu A, Wernig M, Südhof TC. Synaptogenic effect of APP-Swedish mutation in familial Alzheimer's disease. Sci Transl Med. 2022 Oct 19;14(667):eabn9380. PubMed.

University of Florence

These results represent an important step forward to treat AD and offer an encouragement for increasing our efforts in designing new therapeutic strategies against Aβ. Approval by the FDA should be straightforward considering that the deceleration of AD progress occurred with an even higher rate than in the lecanemab trial.

The fact remains that the efficacy of these mAb-based treatments depends on how early the disease is treated. We therefore need to invest in early diagnosis. I also wonder whether many of the previous potential therapeutics against AD that failed in clinical trials should be re-evaluated in clinically normal but biomarker-diagnosed AD cases.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.